That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

~Shakespeare (Sonnet 73)

Pension, considered a reliable comrade of old age, is meant to provide financial security and stability in retirement, ensuring individuals have a dependable income when they are no longer earning. However, in Pakistan, as with many other fiscal challenges, this boon has turned into a bane, battering the fiscal space, which is already largely sapped by inefficient and rent-seeking revenue mobilisation.

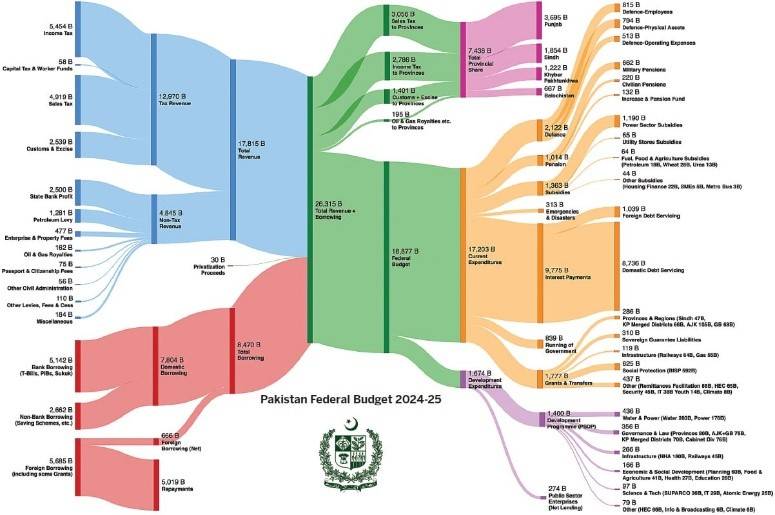

Under the Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) model, pension benefits are funded without employee contributions. This approach has resulted in pension liabilities ballooning to over Rs. 1 trillion in Budget-25 (B-25), with Rs. 260 billion allocated for civil servants and Rs. 750 billion for the armed forces. This represents a staggering 4.4x increase compared to the operational expenses of the civil government, which have only grown 2.7x over the past decade. Alarming projections suggest that pension expenditures will double every four years. Additionally, unfunded pension liabilities are estimated at Rs. 30-35 trillion, surpassing the country’s total external debt.

The pension crisis is also undermining the financial sustainability of already bleeding state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In the B-25, pensions were estimated at Rs. 850 billion, with an astronomical impact on disgruntled institutions like Pakistan Railways—where pensioners outnumber current employees twofold—and Pakistan Post, where one-third of the budgeted expenditure is consumed by pension payments.

The core problem lies in the structural framework of pension schemes. Pakistan predominantly follows a defined benefit (DB) plan, where retirees are guaranteed a fixed pension, often exceeding the last drawn salary when post-retirement allowances are included. This model places the entire financial burden on the employer—in this case, the government—leading to significant fiscal pressures. Furthermore, the risks associated with investment returns and demographic shifts, such as increasing life expectancy, are borne solely by the government, making the system unsustainable in the long term.

Pakistan faces a pivotal moment in tackling mounting pension liabilities, and decisive action is required to prevent this issue from spiraling into a larger fiscal crisis

In contrast, a defined contribution (DC) scheme offers a more sustainable alternative. Under a DC plan, both the employer and employee contribute to a retirement account, and the benefits depend on the accumulated contributions and their investment performance. This model not only distributes the financial burden but also shares the investment risk. Unlike a DB plan, the government has no liability beyond depositing its defined share. This shift fosters fiscal discipline while empowering individuals to take greater control of their retirement planning. Moreover, the DC approach incentivises savings and aligns pension payouts with economic realities, thereby reducing the risk of unfunded liabilities.

Pension reform is fraught with political and social challenges. Any changes to existing pension schemes could face public backlash, potentially decimating the political capital of reformist governments. Further, with military in the equation, the situation complicates into a political enigma. While the government has introduced a contributory fund scheme for new entrants (both civil and armed), with federal employees contributing 10pc of their basic pay and the government will contribute 20pc to the fund, it remains an unresolved conundrum how to address the legacy liabilities of existing pensioners. Lessons can be drawn from India, which has transitioned smoothly from the old DB scheme to the DC system.

Furthermore, recently, the government of Pakistan is considering lowering the retirement age for federal employees from 60 to 55 to reduce the pension bill. However, experts argue this will increase upfront pension costs by extending payments and raising initial payouts. While it may reduce final salary calculations, long-term savings are minimal. This move also contradicts the global trend of raising retirement ages to manage pension costs and could worsen Pakistan’s already unsustainable pension liabilities. Experts recommend parametric reforms and contributory pension schemes as more effective, long-term solutions to address the underlying issues.

Conclusion

Pakistan faces a pivotal moment in tackling mounting pension liabilities, and decisive action is required to prevent this issue from spiraling into a larger fiscal crisis. Adopting a sustainable, multi-pillar pension system—comprising mandatory public contributions, voluntary private savings, and occupational pensions—offers a balanced solution that can alleviate the financial strain on the state while securing a dignified retirement for citizens.

This shift requires both political will and public buy-in, as pension reforms must be approached with sensitivity to the rights of existing pensioners. The introduction of parametric reforms, such as extending the retirement age, modifying pension accrual rates, and rationalising family benefits, is essential to reducing legacy liabilities while maintaining fairness. Furthermore, transitioning from modified cash-based accounting to accrual accounting will provide a more accurate reflection of pension liabilities, ensuring long-term financial planning and sustainability.

To support this transition, the government must prioritise financial literacy initiatives, strengthen governance frameworks, and promote transparency. Only through these efforts can Pakistan build a pension system that not only addresses fiscal challenges but also guarantees economic security for future generations. This is not merely an economic necessity; it is a moral imperative to protect the dignity and well-being of Pakistan’s retirees.