I have always wondered what it means to be a free woman. Most likely, I think about such things because I myself aspire to be one. When I was growing up, I was told that that a free woman was dangerous and that she was someone to be feared. I did not know what she looked like but common descriptions included a hot temper, a sharp tongue and a commitment to disrupting an unjust order as a matter of principle. As I grew older, I read about examples of such women in history and learnt about how rare they were – and how uncommonly kind and courageous too.

Throughout my adult life, I have associated these things with Asma Jahangir.

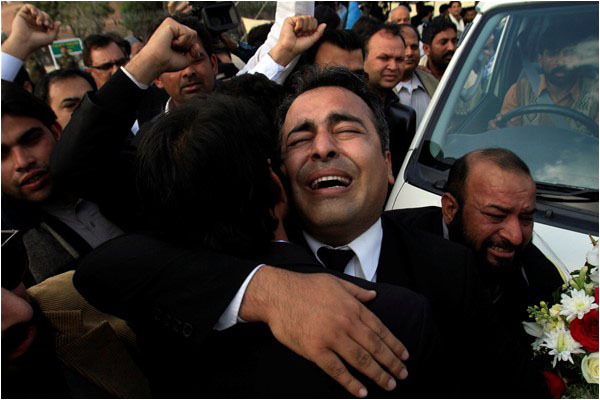

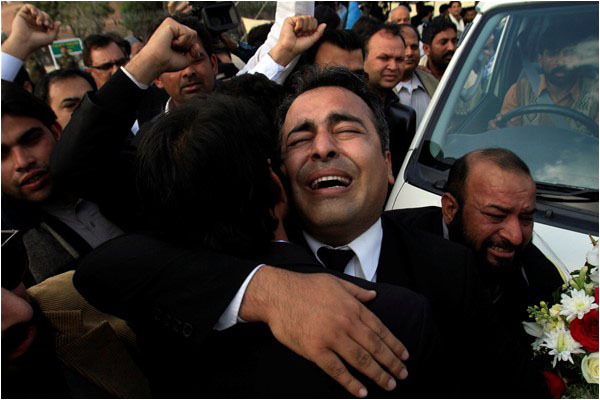

At midday on Tuesday, as I approach her Lahore home where people are to gather before her funeral procession, I see groups of Awami National Party (ANP) stalwarts wearing their iconic red caps entering Qaddafi Stadium. Later in the day, these men join the chorus of voices chanting blessings for her soul as her body passes by them. Activists of the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) – Asma’s very own – bearing their yellow dupattas, hold hands and comfort one another and scores of young women join them as they say goodbye. Lawyers, easily distinguishable with their formal attire, also participate, as they raise slogans for an independent judiciary and pay tributes to Asma’s contributions to the cause of justice. Former information minister Pervaiz Rasheed exits her house with tears in his eyes, gripping journalist Hamid Mir’s hand tightly, who looks as if he, too, needs the support. Later, Rasheed weeps on the street as Asma’s body approaches the stadium, and Jugnu Mohsin, publisher and activist, weeps with him.

No amount of accolades can fully capture the diverse shades of Asma Jahangir’s life and personality, but one thing is clear to me as I stand – a tiny speck in a sea of people – to say goodbye to Asma ji; she lived and died a free woman and she upheld her freedom by fighting for that of others. Everywhere I turn, I see people who are friends, relatives, comrades, admirers and in them I see thousands of struggles that Asma came to represent in her life as a human rights advocate, an activist and a lawyer.

At her funeral, as perhaps her last act of defiance, Asma has brought together those communities of Pakistan who usually do not get much of a say in how things work in this country: democrats, women who suffered injustice and those who are fighting it, Christians, Sikhs, students, progressive activists – and thousands of others who have a stake in a different, better and more humane Pakistan.

As we all line up for prayer, it dawns on me – as I’m sure it does on many others – that Asma ji’s is the first funeral that we are attending in our lives as adult women. We did not bid her farewell at the house and stay behind, as is usually the case even when our close relatives die. Her memory is so powerful, so compelling and so subversive that she beckons us to break new ground – and we follow her much the same as we did when she walked amongst us.

After Farooq Haider Maududi finishes the funeral prayer, there is a melancholic hush as we all move towards one another, seeking the comfort of the familiar. We don’t have to know each other to comfort one another. There is camaraderie here. We embrace one another and unite in recognition of the extraordinary loss that progressives of this country have suffered.

We are good to each other this afternoon – for Asma Jahangir and because of her.

Veteran left-wing political activist Farooq Tariq leads some of the sloganeering on behalf of brick kiln workers, peasants and political prisoners who Asma had represented in her lifetime. He, too, is teary-eyed as he shares his memories of the woman who fought from the front for many of their shared ideals.

“In April 2002, 18 of us were arrested here in Lahore for protesting the referendum held by General Musharraf’s illegal regime. I called Asma from Qilla Gujjar Singh police station and asked her for help. I told her that the police had registered the First Information Report (FIR) and would bring us to court the next morning. When we came to court, Asma was already there. We were not taken out of the police van as we were chanting slogans against Musharraf and the referendum, which was unacceptable to us. While Asma was arguing the case, our voices reached the courtroom and the judge got angry at the disturbance. Asma came out, told us to stop, and went back inside. I suppose the judge liked Asma, he accepted our bail application. She got us released and told us we needed to organise our bail bonds. I told her that I did not have the amount of money set by the court. She looked at me and said, ‘I know you, you are from the Labour Party and your friends are working class people. Don’t worry, I will take care of it.’ She then went back to the judge and presented to him her own property papers for our bail! We were released immediately. No lawyer would do that. Asma was a lawyer by profession and an activist through and through.”

Farooq Tariq continues, “In September 2007, we planned a demonstration in front of Lahore High Court in opposition to Musharraf’s regime. The call for the demonstration had come from the Lahore High Court Bar Association. This was when former chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry had already been restored but we wanted to continue the movement to end Musharraf’s rule. Asma asked me to mobilise workers along with lawyers. We were around 200 that day for the demonstration. I was arrested at the end of the demonstration and 10 kiln workers were arrested with me. In the evening, police registered an FIR under the Anti-Terrorism Act against all of us. We were taken to Anarkali police station. I have never seen a woman as angry as Asma when she came into the police station that day. She was a true Lahori woman! Policemen were hiding in their own office and she yelled at them! ‘Why were these activists not taken to court?’ she demanded to know. Within a few minutes, the superintendent arrived. We were taken to court and Asma argued well. We raised slogans inside the courtroom and the judge did not like that. He put us in judicial remand at Camp Jail. Asma was very angry with the judge. She told him that he was punishing the weakest section of society for speaking up. Within three days, she got us out of jail again.”

Aimen Bucha, who worked closely with Asma ji at AGHS Legal Aid Cell last year, remembers her first conversation with her. “The first time she called me, I was asleep. I picked up and she said, ‘This is Asma.’ I asked, ‘Asma who?’ She paused for a moment and said, ‘Asma Jahangir.’ She was calling me for a job interview at AGHS and at the same time, there was a demonstration for an acid attack victim being held at the Lahore Press Club. I told her this hesitantly. She instantly replied, ‘The protest is very important, why don’t you attend that first and come to me after?’ That is the moment I saw how she encourages everyone to aspire to and practice a politics of justice.”

Aimen also remembers her concern for the wellbeing and safety of activists. “The day before she passed away, she called me and the first question she asked was, are you alright? Are you safe? I hope nothing is bothering you…”

Raza Rumi, editor of Daily Times, in a telephonic conversation with this scribe also shares a poignant memory of her. “When I was attacked by gunmen for my journalistic work a few years ago, Asma ji came to my house to visit me. She didn’t have to – her daughter was getting married and there was a lot of activity at her home. But she took out the time and came over. And I will never forget how she not only emphathised with my situation but also gave me advice as a good friend should.”

Noor Ejaz Chaudhry, a legal associate at AGHS, remembers the time she spent preparing cases with Asma. She speaks of how Asma treated her colleagues: with dignity and respect. “She would ask us our opinions on how to make the case stronger and when we sat late into the night, she would say, ‘Challo. Let’s go get something to eat.’”

There is great fondness in Noor’s voice as she speaks of food runs with Asma ji. “She would always take us to a Chinese place and order soup and mutton. Soup and mutton was her thing…”

“The inheritance that she left behind for me were her pearls of wisdom. She taught me conduct. She taught me ways to not take everything too hard. ‘Don’t get fixated with the details, Noor! Think of the bigger picture!’ she would say.”

Her fondest memory is of the time when the associates introduced her to the concept of the mobile phone dating app, Tinder.

“We had been talking about how we don’t have a love-life. She said to us, ‘Why don’t you have a love-life? You are the best there is!’ One of the boys mentioned that these days, women find love online – through Tinder. She was stunned. ‘What is this? Beta don’t do this on the net…do you know what happened to a boy and a girl in Kashmir?’ And then she proceeded to tell us the story, and how difficult the case had been.”

Her secretary Najam remembers her for her immense humility. “I worked with her for many years. Every morning, I brought in her schedule for the day and the things she needed to look over. We would sit and talk about it before finalising it. One day, I had a terrible flu. I brought her files to her table and told her that today I would sit outside since I didn’t want to pass on the virus. She said to me sternly, “Najam, kaheen jaanay ki zaroorat nahee hai!” (Najam, there is no need to go anywhere!)

So here I am, at Asma ji’s funeral. I see women, men, Catholic nuns, Protestants and turbaned Sikh gents. I see peasant activists from the Anjuman-e-Muzaraeen. There are lawyers, judges, politicians and journalists – all being their very best in this deeply troubled and unjust society. Here, right in front of me, is a vision of what this country could be.

But the visionary is gone and now we are on our own.

Aima Khosa is an editor for Vanguard Books. She tweets at @aimamk

Throughout my adult life, I have associated these things with Asma Jahangir.

At midday on Tuesday, as I approach her Lahore home where people are to gather before her funeral procession, I see groups of Awami National Party (ANP) stalwarts wearing their iconic red caps entering Qaddafi Stadium. Later in the day, these men join the chorus of voices chanting blessings for her soul as her body passes by them. Activists of the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) – Asma’s very own – bearing their yellow dupattas, hold hands and comfort one another and scores of young women join them as they say goodbye. Lawyers, easily distinguishable with their formal attire, also participate, as they raise slogans for an independent judiciary and pay tributes to Asma’s contributions to the cause of justice. Former information minister Pervaiz Rasheed exits her house with tears in his eyes, gripping journalist Hamid Mir’s hand tightly, who looks as if he, too, needs the support. Later, Rasheed weeps on the street as Asma’s body approaches the stadium, and Jugnu Mohsin, publisher and activist, weeps with him.

As we all line up for prayer, it dawns on me - as I'm sure it does on many others - that Asma ji's is the first funeral that we are attending in our lives as adult women.

No amount of accolades can fully capture the diverse shades of Asma Jahangir’s life and personality, but one thing is clear to me as I stand – a tiny speck in a sea of people – to say goodbye to Asma ji; she lived and died a free woman and she upheld her freedom by fighting for that of others. Everywhere I turn, I see people who are friends, relatives, comrades, admirers and in them I see thousands of struggles that Asma came to represent in her life as a human rights advocate, an activist and a lawyer.

At her funeral, as perhaps her last act of defiance, Asma has brought together those communities of Pakistan who usually do not get much of a say in how things work in this country: democrats, women who suffered injustice and those who are fighting it, Christians, Sikhs, students, progressive activists – and thousands of others who have a stake in a different, better and more humane Pakistan.

As we all line up for prayer, it dawns on me – as I’m sure it does on many others – that Asma ji’s is the first funeral that we are attending in our lives as adult women. We did not bid her farewell at the house and stay behind, as is usually the case even when our close relatives die. Her memory is so powerful, so compelling and so subversive that she beckons us to break new ground – and we follow her much the same as we did when she walked amongst us.

After Farooq Haider Maududi finishes the funeral prayer, there is a melancholic hush as we all move towards one another, seeking the comfort of the familiar. We don’t have to know each other to comfort one another. There is camaraderie here. We embrace one another and unite in recognition of the extraordinary loss that progressives of this country have suffered.

We are good to each other this afternoon – for Asma Jahangir and because of her.

Veteran left-wing political activist Farooq Tariq leads some of the sloganeering on behalf of brick kiln workers, peasants and political prisoners who Asma had represented in her lifetime. He, too, is teary-eyed as he shares his memories of the woman who fought from the front for many of their shared ideals.

“In April 2002, 18 of us were arrested here in Lahore for protesting the referendum held by General Musharraf’s illegal regime. I called Asma from Qilla Gujjar Singh police station and asked her for help. I told her that the police had registered the First Information Report (FIR) and would bring us to court the next morning. When we came to court, Asma was already there. We were not taken out of the police van as we were chanting slogans against Musharraf and the referendum, which was unacceptable to us. While Asma was arguing the case, our voices reached the courtroom and the judge got angry at the disturbance. Asma came out, told us to stop, and went back inside. I suppose the judge liked Asma, he accepted our bail application. She got us released and told us we needed to organise our bail bonds. I told her that I did not have the amount of money set by the court. She looked at me and said, ‘I know you, you are from the Labour Party and your friends are working class people. Don’t worry, I will take care of it.’ She then went back to the judge and presented to him her own property papers for our bail! We were released immediately. No lawyer would do that. Asma was a lawyer by profession and an activist through and through.”

Farooq Tariq continues, “In September 2007, we planned a demonstration in front of Lahore High Court in opposition to Musharraf’s regime. The call for the demonstration had come from the Lahore High Court Bar Association. This was when former chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry had already been restored but we wanted to continue the movement to end Musharraf’s rule. Asma asked me to mobilise workers along with lawyers. We were around 200 that day for the demonstration. I was arrested at the end of the demonstration and 10 kiln workers were arrested with me. In the evening, police registered an FIR under the Anti-Terrorism Act against all of us. We were taken to Anarkali police station. I have never seen a woman as angry as Asma when she came into the police station that day. She was a true Lahori woman! Policemen were hiding in their own office and she yelled at them! ‘Why were these activists not taken to court?’ she demanded to know. Within a few minutes, the superintendent arrived. We were taken to court and Asma argued well. We raised slogans inside the courtroom and the judge did not like that. He put us in judicial remand at Camp Jail. Asma was very angry with the judge. She told him that he was punishing the weakest section of society for speaking up. Within three days, she got us out of jail again.”

"I have never seen a woman as angry as Asma when she came into the police station that day. She was a true Lahori woman! Policemen were hiding in their own office and she yelled at them! 'Why were these activists not taken to court?' she demanded to know" (Farooq Tariq)

Aimen Bucha, who worked closely with Asma ji at AGHS Legal Aid Cell last year, remembers her first conversation with her. “The first time she called me, I was asleep. I picked up and she said, ‘This is Asma.’ I asked, ‘Asma who?’ She paused for a moment and said, ‘Asma Jahangir.’ She was calling me for a job interview at AGHS and at the same time, there was a demonstration for an acid attack victim being held at the Lahore Press Club. I told her this hesitantly. She instantly replied, ‘The protest is very important, why don’t you attend that first and come to me after?’ That is the moment I saw how she encourages everyone to aspire to and practice a politics of justice.”

Aimen also remembers her concern for the wellbeing and safety of activists. “The day before she passed away, she called me and the first question she asked was, are you alright? Are you safe? I hope nothing is bothering you…”

Raza Rumi, editor of Daily Times, in a telephonic conversation with this scribe also shares a poignant memory of her. “When I was attacked by gunmen for my journalistic work a few years ago, Asma ji came to my house to visit me. She didn’t have to – her daughter was getting married and there was a lot of activity at her home. But she took out the time and came over. And I will never forget how she not only emphathised with my situation but also gave me advice as a good friend should.”

Noor Ejaz Chaudhry, a legal associate at AGHS, remembers the time she spent preparing cases with Asma. She speaks of how Asma treated her colleagues: with dignity and respect. “She would ask us our opinions on how to make the case stronger and when we sat late into the night, she would say, ‘Challo. Let’s go get something to eat.’”

There is great fondness in Noor’s voice as she speaks of food runs with Asma ji. “She would always take us to a Chinese place and order soup and mutton. Soup and mutton was her thing…”

“The inheritance that she left behind for me were her pearls of wisdom. She taught me conduct. She taught me ways to not take everything too hard. ‘Don’t get fixated with the details, Noor! Think of the bigger picture!’ she would say.”

Her fondest memory is of the time when the associates introduced her to the concept of the mobile phone dating app, Tinder.

“We had been talking about how we don’t have a love-life. She said to us, ‘Why don’t you have a love-life? You are the best there is!’ One of the boys mentioned that these days, women find love online – through Tinder. She was stunned. ‘What is this? Beta don’t do this on the net…do you know what happened to a boy and a girl in Kashmir?’ And then she proceeded to tell us the story, and how difficult the case had been.”

Her secretary Najam remembers her for her immense humility. “I worked with her for many years. Every morning, I brought in her schedule for the day and the things she needed to look over. We would sit and talk about it before finalising it. One day, I had a terrible flu. I brought her files to her table and told her that today I would sit outside since I didn’t want to pass on the virus. She said to me sternly, “Najam, kaheen jaanay ki zaroorat nahee hai!” (Najam, there is no need to go anywhere!)

So here I am, at Asma ji’s funeral. I see women, men, Catholic nuns, Protestants and turbaned Sikh gents. I see peasant activists from the Anjuman-e-Muzaraeen. There are lawyers, judges, politicians and journalists – all being their very best in this deeply troubled and unjust society. Here, right in front of me, is a vision of what this country could be.

But the visionary is gone and now we are on our own.

Aima Khosa is an editor for Vanguard Books. She tweets at @aimamk