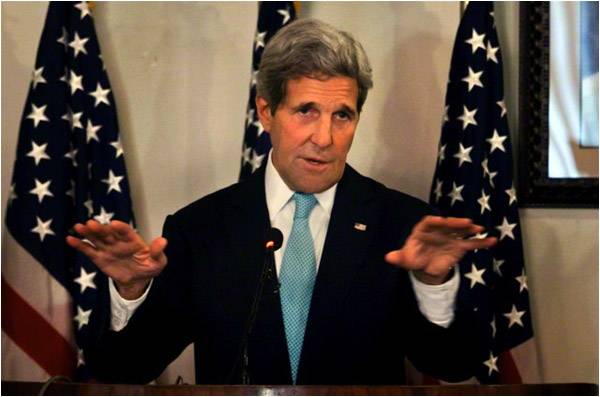

The recent visit of US Secretary of State John Kerry to Islamabad is a continuation of the improving relations between Pakistan and the US. From the declared frenemies in 2011, things have changed thereby proving that nothing is permanent in international relations except interests.

Kerry during his visit lauded Pakistan’s ongoing fight against terrorism and urged the authorities to take action against militant groups that threaten regional peace and stability. Furthermore, the State Department has declared Mullah Fazalluah, commander of TTP fighting Pakistani military, a global terrorist and froze his US assets, if any. On Tuesday, Afghan authorities reportedly apprehended 5 suspected planners of the Peshawar school attack based on the intelligence shared by Pakistan. This came after the weekend visit of Pakistani intelligence chief to Kabul and his meeting with President Ghani.

What distinguished Kerry’s current visit from earlier visits by US officials was that Pakistan Defence Council and other such xenophobic networks did not carry out public demonstrations against the US. A clear effort was made that such an embarrassment is avoided. Phrases such as ‘drone strikes’ and ‘violations of sovereignty’ were missing in the official communiques. Both countries are back to their old military to military relationship and trust deficit has considerably narrowed.

Earlier, General Raheel Sharif, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, spent two weeks in the US in November 2014 where he met top military and civilian officials including Secretary Kerry. For Pakistan, facilities such as the Coalition Support Fund (CSF) seem to be functional without the earlier hiccups.

The CSF was renewed in end 2014 with certain limitations. For other releases such as the promised $532 million, the US administration may use a national interest waiver to transfer the funds. In 2014, the US agreed to sell 160 mine resistant ambush protected vehicles, for the military campaign in North Waziristan. Pakistani military’s decisive Operation Zarb-e-Azb launched in June 2014 has been a turning point of sorts. Pakistan’s official line is that there are no good or bad Taliban anymore. The US views Pakistan as a key actor in forging a peace deal between the factions of Afghan Taliban and Kabul. Whether these goals are realized or not remains to be seen.

A recent book by Daniel Markey, a senior fellow for South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, ‘No Exit from Pakistan: America’s Tortured Relationship with Islamabad’ reviews the historical trajectory of the bilateral relations but also presents a set of policy options for the US.

The first option Markey highlighted was ‘defensive isolation’ but argued that this might be counter productive turning Pakistan into an adversary. The second option outlined was restricting the relationship to military-to-military relations. Such a transactional relationship has defined the decades of US-Pakistan cooperation and perhaps we are seeing more of this in the present context. The third option presented was ‘comprehensive cooperation’ that was tried by the Obama administration with mixed results.

Markey’s recipe was more nuanced than what many in Washington currently suggest. In his view, the bilateral relationship has to be managed through “patient, sustained effort, not by way of quick fixes or neglect” with the ultimate aim of ‘managing threats’. In short, Markey suggested that US could not forsake its relationship with Pakistan.

Noting how “Washington has viewed the country as a means to other ends”, Markey tried to be dispassionate about the US policy flaws in the past. At the same time the book offers a comprehensive overview of the anti-Americanism within Pakistan and therefore contextualizes the phenomena in a complex history of Cold War and beyond. “Pakistan’s leaders tend to be tough negotiators with high thresholds for pain, Washington can cut new deals and level credible threats to achieve US goals. This is not a friendly game, but out of it both sides can still benefit”, wrote Markey.

An urgent imperative in the long term is to transform the US-Pakistan relationship into an economic one. There are nearly a million Pakistanis in the US who contribute the third largest share of remittances to Pakistan. As Markey noted in his book, Pakistan’s youth wants education, opportunities and integration into the global world of ideas and jobs. One of the identities that Markey attributes to Pakistan is that of a “youthful idealist, teeming with energy and reform-minded ambition.” Artistic expressions from Pakistan have lampooned the way country’s elites use the US bogey as well as how the US acts as an indifferent big power and easily abandons Pakistan.

There is far greater room for trade, investment, education and cultural cooperation between the two countries than the two governments imagine. For decades this relationship has been locked in the security prism that continues to paint a unidimensional view of Pakistan to the US media and policymakers.

In Pakistan, there is a shift underway as well. The new heads of the Army and ISI appear to be different than their predecessors. While civilian input informs, the leverage of elected government is limited. Foreign policy and the ancillary security policy vis-à-vis Afghanistan and the tribal regions is by and large under the purview of the military.

Events such as the December 16 massacre of children in an Army school have jolted the entire country and there is a renewed vigour to tackle terrorism. How far will the military go remains to be seen. But it is not going to be a replay of the Kayani-Pasha engagement.

The public sentiment in Pakistan is largely managed by the vernacular media, which in turn has deep ties with the security establishment. This is why since June 2014 there have been multiple drone attacks and the outcry has been negligible. While this may be beneficial for the relationship for now, in the long term an informed public opinion is what Pakistan needs.

The Pakistan-US relationship needs more imagination on both sides. While the Kerry-Lugar-Berman assistance design may not have worked as planned, there is still a need to engage with Pakistan’s civil society and democratic institutions. Only a democratic, plural Pakistan can be a peaceful polity and a responsible regional nuclear power. This is a lesson that the US must not forget; and more importantly Pakistan’s civilians must not overlook. Despite the odds they will have to reset many policy buttons even if it takes long.

Kerry during his visit lauded Pakistan’s ongoing fight against terrorism and urged the authorities to take action against militant groups that threaten regional peace and stability. Furthermore, the State Department has declared Mullah Fazalluah, commander of TTP fighting Pakistani military, a global terrorist and froze his US assets, if any. On Tuesday, Afghan authorities reportedly apprehended 5 suspected planners of the Peshawar school attack based on the intelligence shared by Pakistan. This came after the weekend visit of Pakistani intelligence chief to Kabul and his meeting with President Ghani.

What distinguished Kerry’s current visit from earlier visits by US officials was that Pakistan Defence Council and other such xenophobic networks did not carry out public demonstrations against the US. A clear effort was made that such an embarrassment is avoided. Phrases such as ‘drone strikes’ and ‘violations of sovereignty’ were missing in the official communiques. Both countries are back to their old military to military relationship and trust deficit has considerably narrowed.

Earlier, General Raheel Sharif, Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, spent two weeks in the US in November 2014 where he met top military and civilian officials including Secretary Kerry. For Pakistan, facilities such as the Coalition Support Fund (CSF) seem to be functional without the earlier hiccups.

Operation Zarb-e-Azb has been a turning point of sorts

The CSF was renewed in end 2014 with certain limitations. For other releases such as the promised $532 million, the US administration may use a national interest waiver to transfer the funds. In 2014, the US agreed to sell 160 mine resistant ambush protected vehicles, for the military campaign in North Waziristan. Pakistani military’s decisive Operation Zarb-e-Azb launched in June 2014 has been a turning point of sorts. Pakistan’s official line is that there are no good or bad Taliban anymore. The US views Pakistan as a key actor in forging a peace deal between the factions of Afghan Taliban and Kabul. Whether these goals are realized or not remains to be seen.

A recent book by Daniel Markey, a senior fellow for South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations, ‘No Exit from Pakistan: America’s Tortured Relationship with Islamabad’ reviews the historical trajectory of the bilateral relations but also presents a set of policy options for the US.

The first option Markey highlighted was ‘defensive isolation’ but argued that this might be counter productive turning Pakistan into an adversary. The second option outlined was restricting the relationship to military-to-military relations. Such a transactional relationship has defined the decades of US-Pakistan cooperation and perhaps we are seeing more of this in the present context. The third option presented was ‘comprehensive cooperation’ that was tried by the Obama administration with mixed results.

Markey’s recipe was more nuanced than what many in Washington currently suggest. In his view, the bilateral relationship has to be managed through “patient, sustained effort, not by way of quick fixes or neglect” with the ultimate aim of ‘managing threats’. In short, Markey suggested that US could not forsake its relationship with Pakistan.

Noting how “Washington has viewed the country as a means to other ends”, Markey tried to be dispassionate about the US policy flaws in the past. At the same time the book offers a comprehensive overview of the anti-Americanism within Pakistan and therefore contextualizes the phenomena in a complex history of Cold War and beyond. “Pakistan’s leaders tend to be tough negotiators with high thresholds for pain, Washington can cut new deals and level credible threats to achieve US goals. This is not a friendly game, but out of it both sides can still benefit”, wrote Markey.

An urgent imperative in the long term is to transform the US-Pakistan relationship into an economic one. There are nearly a million Pakistanis in the US who contribute the third largest share of remittances to Pakistan. As Markey noted in his book, Pakistan’s youth wants education, opportunities and integration into the global world of ideas and jobs. One of the identities that Markey attributes to Pakistan is that of a “youthful idealist, teeming with energy and reform-minded ambition.” Artistic expressions from Pakistan have lampooned the way country’s elites use the US bogey as well as how the US acts as an indifferent big power and easily abandons Pakistan.

There is far greater room for trade, investment, education and cultural cooperation between the two countries than the two governments imagine. For decades this relationship has been locked in the security prism that continues to paint a unidimensional view of Pakistan to the US media and policymakers.

In Pakistan, there is a shift underway as well. The new heads of the Army and ISI appear to be different than their predecessors. While civilian input informs, the leverage of elected government is limited. Foreign policy and the ancillary security policy vis-à-vis Afghanistan and the tribal regions is by and large under the purview of the military.

Events such as the December 16 massacre of children in an Army school have jolted the entire country and there is a renewed vigour to tackle terrorism. How far will the military go remains to be seen. But it is not going to be a replay of the Kayani-Pasha engagement.

The public sentiment in Pakistan is largely managed by the vernacular media, which in turn has deep ties with the security establishment. This is why since June 2014 there have been multiple drone attacks and the outcry has been negligible. While this may be beneficial for the relationship for now, in the long term an informed public opinion is what Pakistan needs.

The Pakistan-US relationship needs more imagination on both sides. While the Kerry-Lugar-Berman assistance design may not have worked as planned, there is still a need to engage with Pakistan’s civil society and democratic institutions. Only a democratic, plural Pakistan can be a peaceful polity and a responsible regional nuclear power. This is a lesson that the US must not forget; and more importantly Pakistan’s civilians must not overlook. Despite the odds they will have to reset many policy buttons even if it takes long.