Many detractors of Prime Minister Imran Khan have been accusing him of following General Zia-ul-Haq's policies. They claim that extreme self-censorship, stifling of dissent, violations of human rights, violence against minorities and witch-hunting of political opponents reminds one of Zia’s times. Yet there are even some who believe that Khan’s style of government is more lethal than that of brutal dictator whose dark era corrupted politics, sowed the seeds of religious hatred, fanned ethnic tensions and tore the social fabric of Pakistani society. Is this a sober analysis or an excessive claim?

Khan's opponents believe that he is perhaps the first Pakistani politician who moved from political sagacity to political immaturity. For instance, if one goes through his interviews from the Musharraf era, one notices that most such interviews reflected political acumen and bitter realities of Pakistani politics. Almost in all of these interviews, Khan lambasted anti-democratic forces of the country, accusing them of manipulating elections, promoting corrupt politicians, bankrolling sectarian forces, patronising ethnic elements and jumping into the wars and conflicts that had nothing to do with the national interest of the country.

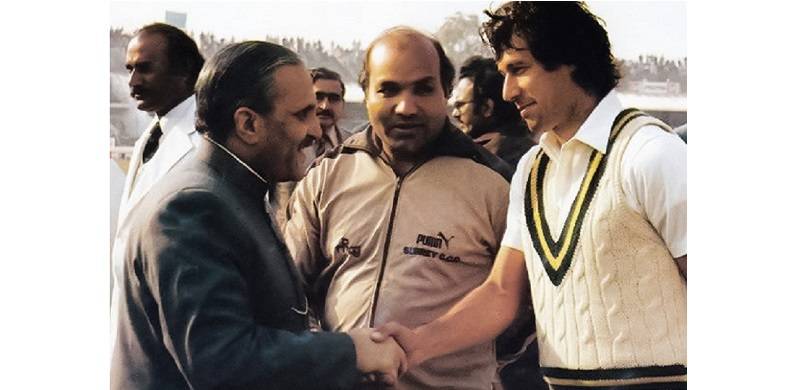

Ironically, when the same non-democratic forces cobbled together an alliance of corrupt politicians, forcing them to join the ranks of the PTI, Khan not only greeted them with open arms but he also heaped eulogies on these turncoats, besides declaring them the men of conscience who risked their political careers by putting an end to their association with what he called corrupt political dynasties. Such a sanctimonious posture was even missing in the demeanour of Zia who, knew very well that they were unscrupulous electables who could go to any extent to protect their interests. But our modern-day Mr. Clean of Pakistani politics allowed these unconscientious feudals, tribal lords and money-makers to fill his right and left flanks.

It was because of such an attitude that even some of his supporters from the middle and lower classes started taking whatever Khan claimed with a pinch of salt, wondering as to how Khan would improve government schools when he himself is accompanied by the people who own private schools and whose business can only thrive if the educational standards at state-run schools are pathetic. They also questioned the rationality of inducting people from pharmaceutical businesses while making tall claims of providing free and quality medical treatment. Khan did not disappoint his critics with his buddies allowing pharmaceutical companies to make an exponential increase in the prices of medicines.

Khan also came up with policies that appeased the traditional influential classes in Pakistani society like textile, stock exchanges, car imports and other lobbies. He showered favours on these classes, withdrawing the subsidies that were being extended to the poor in the past. The Kaptaan doled out a package on stock exchanges soon after coming into power beside announcing a Rs 1,200 billion relief for the rich during the pandemic, allocating a meagre Rs 150 billion for the people from the bottom layer of social stratification, who were worst hit by the contagion.

General Zia had also adopted such a hypocritical attitude, but what was most harmful from a myriad of his policies was his exploitation of religion for political purposes. The dictator invoked religious injunctions, symbols and connotations to perpetuate his illegal rule, besides granting a carte blanche to obscurantist forces of society and the clergy – which did great damage to the country's social fabric. Consequently, the pernicious tentacles of sectarian forces gripped Pakistani society, plunging the country into an abyss of religious bigotry.

Khan seems to be following the legacy of his ideological predecessor Zia, appeasing the soul of his political mentor General Hamid Gul, whose concept of strategic depth and myopic worldview not only spawned jihadi and militant organisations but also contributed, in a way, to the killing of tens of thousands of Pakistanis during the Taliban insurgency, besides leading to the loss of over $100 billion to the Pakistani economy because of the havoc wreaked by extremist forces who idolised the late Gul.

Arguably, the most alarming aspect of Khan's style of governance is the appeasement of the religious right. The Kaptaan has not only inducted a notorious sectarian figure who would heap scorn on a particular sect publicly, as his special assistant, but he also encouraged religious fascists by picking orthodox clerics to run the country's religious affairs ministry. Such appointments encouraged rabidly anti-Shi’ite groups to mount their lethal offensive against the community, prompting some of the lawmakers of the provincial assembly to introduce laws that would further damage the social fabric of the country. Such a policy also encouraged Barelvi groups to assert their authority, who were bankrolled by non-democratic forces for being N-league opponents. A top PTI leader from Punjab openly talked about the possibility of working with these rising fascist forces. Such a move would mainstream these hatemongers who are looking to promote mob-lynching and challenge the writ of the state.

Like his dictatorial predecessor, Khan is promoting medieval thinking by carrying out radical changes in the syllabus and throwing millions of rupees behind conservative elements like the clerics of Jamia Haqqania at Akora Khattak. Khan, like Zia, seems to loathe Western education, drastically reducing the budget of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) while at the same time pumping millions – or possibly billions – of rupees into the establishment of various religious authorities and research centres that would not attempt to create or invent something, but invest their all energies in deciphering the inner message of some figures of folklore. Khan's governor in Punjab is also trying to change the educational system at college and university levels in a way that would lead to the stuffing of higher educational institutions with conservative elements. Instead of modernising seminaries, he seems to be converting state-run schools into religious institutions, which would further promote the very narrow interpretation of religion that has done great harm to the social fabric of the country in the past.

What the Kaptan has added to the legacy of general Zia is the element of superstition. The late dictator was Machiavellian, but he was not superstitious. He would try to run the affairs of state in a cunning way, which reflected a modicum of rationality. But Khan seems to have dragged superstitions into the affairs of state, forcing the powerful elements of the Islamic Republic to remind him that governments are not run in this way. His actions could prompt gullible masses to consider superstitions a source of blessing, which might plunge the country into more intellectual backwardness.

The use of religion for political purposes has always boomeranged on those who came up with the idea of such exploitation. Gandhi employed religious symbols and ideas during his political meetings, campaigns and gatherings, which at the end of the day not only encouraged extremist Hindus to turn India into a theocracy, but also led them to eliminate those who opposed Hindutva, including Gandhi himself. Indonesia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Afghanistan also suffered because of the exploitation of religion for political objectives. After the death of Zia, it was expected that Pakistani politicians would not resort to the exploitation of religion for political purposes. Some did after 1988, but regretted it later, focusing on the issues of governance, attempting to solve the problems of common people. But Khan revitalised this employment of religion, which could be very catastrophic for the country.

So it is perhaps reasonable to argue that his legacy could turn out to be more lethal than that of General Zia, because the champion of change is not merely adopting the right-wing agenda of the dictator but also adding the element of superstition. It is, indeed, a destructive combination.

Khan's opponents believe that he is perhaps the first Pakistani politician who moved from political sagacity to political immaturity. For instance, if one goes through his interviews from the Musharraf era, one notices that most such interviews reflected political acumen and bitter realities of Pakistani politics. Almost in all of these interviews, Khan lambasted anti-democratic forces of the country, accusing them of manipulating elections, promoting corrupt politicians, bankrolling sectarian forces, patronising ethnic elements and jumping into the wars and conflicts that had nothing to do with the national interest of the country.

Ironically, when the same non-democratic forces cobbled together an alliance of corrupt politicians, forcing them to join the ranks of the PTI, Khan not only greeted them with open arms but he also heaped eulogies on these turncoats, besides declaring them the men of conscience who risked their political careers by putting an end to their association with what he called corrupt political dynasties. Such a sanctimonious posture was even missing in the demeanour of Zia who, knew very well that they were unscrupulous electables who could go to any extent to protect their interests. But our modern-day Mr. Clean of Pakistani politics allowed these unconscientious feudals, tribal lords and money-makers to fill his right and left flanks.

It was because of such an attitude that even some of his supporters from the middle and lower classes started taking whatever Khan claimed with a pinch of salt, wondering as to how Khan would improve government schools when he himself is accompanied by the people who own private schools and whose business can only thrive if the educational standards at state-run schools are pathetic. They also questioned the rationality of inducting people from pharmaceutical businesses while making tall claims of providing free and quality medical treatment. Khan did not disappoint his critics with his buddies allowing pharmaceutical companies to make an exponential increase in the prices of medicines.

Khan also came up with policies that appeased the traditional influential classes in Pakistani society like textile, stock exchanges, car imports and other lobbies. He showered favours on these classes, withdrawing the subsidies that were being extended to the poor in the past. The Kaptaan doled out a package on stock exchanges soon after coming into power beside announcing a Rs 1,200 billion relief for the rich during the pandemic, allocating a meagre Rs 150 billion for the people from the bottom layer of social stratification, who were worst hit by the contagion.

General Zia had also adopted such a hypocritical attitude, but what was most harmful from a myriad of his policies was his exploitation of religion for political purposes. The dictator invoked religious injunctions, symbols and connotations to perpetuate his illegal rule, besides granting a carte blanche to obscurantist forces of society and the clergy – which did great damage to the country's social fabric. Consequently, the pernicious tentacles of sectarian forces gripped Pakistani society, plunging the country into an abyss of religious bigotry.

Khan seems to be following the legacy of his ideological predecessor Zia, appeasing the soul of his political mentor General Hamid Gul, whose concept of strategic depth and myopic worldview not only spawned jihadi and militant organisations but also contributed, in a way, to the killing of tens of thousands of Pakistanis during the Taliban insurgency, besides leading to the loss of over $100 billion to the Pakistani economy because of the havoc wreaked by extremist forces who idolised the late Gul.

Arguably, the most alarming aspect of Khan's style of governance is the appeasement of the religious right. The Kaptaan has not only inducted a notorious sectarian figure who would heap scorn on a particular sect publicly, as his special assistant, but he also encouraged religious fascists by picking orthodox clerics to run the country's religious affairs ministry. Such appointments encouraged rabidly anti-Shi’ite groups to mount their lethal offensive against the community, prompting some of the lawmakers of the provincial assembly to introduce laws that would further damage the social fabric of the country. Such a policy also encouraged Barelvi groups to assert their authority, who were bankrolled by non-democratic forces for being N-league opponents. A top PTI leader from Punjab openly talked about the possibility of working with these rising fascist forces. Such a move would mainstream these hatemongers who are looking to promote mob-lynching and challenge the writ of the state.

Like his dictatorial predecessor, Khan is promoting medieval thinking by carrying out radical changes in the syllabus and throwing millions of rupees behind conservative elements like the clerics of Jamia Haqqania at Akora Khattak. Khan, like Zia, seems to loathe Western education, drastically reducing the budget of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) while at the same time pumping millions – or possibly billions – of rupees into the establishment of various religious authorities and research centres that would not attempt to create or invent something, but invest their all energies in deciphering the inner message of some figures of folklore. Khan's governor in Punjab is also trying to change the educational system at college and university levels in a way that would lead to the stuffing of higher educational institutions with conservative elements. Instead of modernising seminaries, he seems to be converting state-run schools into religious institutions, which would further promote the very narrow interpretation of religion that has done great harm to the social fabric of the country in the past.

What the Kaptan has added to the legacy of general Zia is the element of superstition. The late dictator was Machiavellian, but he was not superstitious. He would try to run the affairs of state in a cunning way, which reflected a modicum of rationality. But Khan seems to have dragged superstitions into the affairs of state, forcing the powerful elements of the Islamic Republic to remind him that governments are not run in this way. His actions could prompt gullible masses to consider superstitions a source of blessing, which might plunge the country into more intellectual backwardness.

The use of religion for political purposes has always boomeranged on those who came up with the idea of such exploitation. Gandhi employed religious symbols and ideas during his political meetings, campaigns and gatherings, which at the end of the day not only encouraged extremist Hindus to turn India into a theocracy, but also led them to eliminate those who opposed Hindutva, including Gandhi himself. Indonesia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Afghanistan also suffered because of the exploitation of religion for political objectives. After the death of Zia, it was expected that Pakistani politicians would not resort to the exploitation of religion for political purposes. Some did after 1988, but regretted it later, focusing on the issues of governance, attempting to solve the problems of common people. But Khan revitalised this employment of religion, which could be very catastrophic for the country.

So it is perhaps reasonable to argue that his legacy could turn out to be more lethal than that of General Zia, because the champion of change is not merely adopting the right-wing agenda of the dictator but also adding the element of superstition. It is, indeed, a destructive combination.