The debate surrounding the recent iteration of FATA reforms has missed a fundamental point: there is complete consensus on two aspects of change in FATA, the repeal of the FCR’s egregious facets and the commencement of large-scale economic development.

As such, these lowest common denominators were the natural starting point of reform. They would improve the welfare of FATA’s residents. The subordination of this low-hanging fruit to changes in FATA’s administrative identity suggests that perhaps the reforms were rushed or that an improvement in the people’s welfare is not the prime motivation.

The reforms threw up three choices and went with one: the merger of FATA with Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Even the committee’s staunchest proponents cannot earnestly claim that this choice was made after taking into account the will of the people of FATA. Day-long visits to the agencies and an audience with select delegates were reminiscent of colonial attempts at achieving authenticity. Indeed the greatest criticism of the reforms is that it is paternalistic, as it aimed at replacing one bureaucratic choice with another.

Each administrative option highlighted by the committee is a choice with specific benefits and drawbacks. Democratic principles dictate that the residents of FATA be allowed to choose among them. There is no clear indication of what exactly the people of FATA prefer. Some surveys do get quoted in support of a merger but what is left unstated is the efficacy of polling and the validity of the fundamental laws of sampling design in a war zone that grants limited access and a good chunk of whose population has been displaced. If political questions could be predicted by surveys, the US would have seen its first female president and the United Kingdom would not be grappling with Brexit.

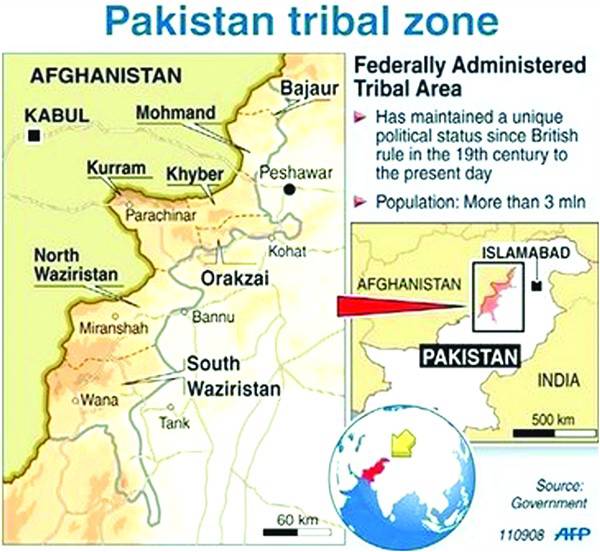

If fundamental rights and economic development can be achieved under all three options presented by the committee, why has a merger been favoured? The experience of Malakand and the provincially administered tribal areas are not happy ones, with FATA being on a different scale altogether. Some arguments marshalled in favor of a merger also ring hollow. Should FATA be merged simply because the agencies are not internally integrated? The isolation of the agencies was a colonial policy and in the present, when motorways are being constructed across the length and breadth of the country, certainly one that links Bajaur to South Waziristan is not beyond the capabilities of the state.

The fact that the residents of FATA are co-ethnics to the majority of KP’s population is a stronger argument, with even some allusions being made to the reunification of East and West Germany. This line of reasoning circles back to the manifesto of the National Awami Party, which called for the creation of linguistic provinces and reneged on that manifesto at the dissolution of One Unit in 1970.

While India was able to undercut regional rivalries by creating linguistic units, the state in Pakistan has been antithetical to the concept. There is no indication that this principle has been conceded in the case of FATA. The example of German unification is also instructive in the consequences of rushed political unions between contrasting governance systems. Due to the speed of the process and specific policy choices, East Germany has become an industrial hinterland with net migration to the erstwhile West, the scale of resources invested notwithstanding. For FATA, the prospect of ending up even more neglected than KP’s southern districts are quite real.

A rather more apt analogy would be that of Puerto Rico - an American territory that would benefit from a change in status. There have been calls on the territory for a closer relationship with the US but as the 51st state and not as an appendage to Florida, the closest state on the American mainland. There are clear advantages to being declared a province. Principal amongst them is a guaranteed share of the NFC pie. This share does not automatically accrue to FATA in case of a merger and proposals for ring fencing the budget are impractical - think South Punjab. However, new provinces ring alarm bells in Pakistan’s stymied polity since they raise the specter of a precedent for all the other three.

The third option is of a more viable autonomy, a continuation of FATA’s status but with the added accoutrements of an elected legislative council, assured budget and its own administrative apex. This third option is dismissed as being another Gilgit-Baltistan (incidentally another autonomous region that demands an upgrade) and discounts the possibility of negotiating a special dispensation, say GB+.

Yet FATA’s case is special; from its novel status in the constitution, to being subjected to inhuman colonial laws and economic neglect. The region has played a role in capturing for Pakistan what is now Azad Kashmir. It has a frontline status in the continuing war in Afghanistan. Its people have braved global terrorism and the indignity of mass displacement due to military operations. If any people have a claim for special dispensation it is the residents of FATA.

For some proponents of a merger the unwillingness to negotiate the best possible deal and acquiescence to what has been offered belies a sense of hapless desperation. The latest round of reforms have been framed as a closing opportunity to take advantage of a bureaucratic fiat, as if what is on offer is a privilege and not solemn rights. Although it might have been intended as a clever campaign tactic, the obfuscation of opposition-to-merger with opposition-to-reform has been a disservice to fostering a credible debate. A lack of debate denies the essence of any reform. Polities brought about as a result of violence often get trapped in cycles of violence whereas structures created by political action prove more responsive to their residents.

Consulting FATA residents and creating ownership of this process is essential. FATA evokes concern within Pakistan for a host of reasons, but beyond our borders these concerns are solely security-centric. Yet tinkering with FATA’s administrative status is not a panacea; after all, the region has the harshest administrative environment in the country. If regular administration were an effective bulwark against militancy, two of our provincial capitals would not have been globally known as eponyms of militant leadership councils. Tackling militancy requires changes in policy, usually in response to coherent and effective calls for change. The sit-in recently held in Islamabad proves that the people of FATA do not lack agency and are capable of voicing their preferences and negotiating peacefully. Their exclusion from what is surely a momentous decision about their future is criminal.

As such, these lowest common denominators were the natural starting point of reform. They would improve the welfare of FATA’s residents. The subordination of this low-hanging fruit to changes in FATA’s administrative identity suggests that perhaps the reforms were rushed or that an improvement in the people’s welfare is not the prime motivation.

The reforms threw up three choices and went with one: the merger of FATA with Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. Even the committee’s staunchest proponents cannot earnestly claim that this choice was made after taking into account the will of the people of FATA. Day-long visits to the agencies and an audience with select delegates were reminiscent of colonial attempts at achieving authenticity. Indeed the greatest criticism of the reforms is that it is paternalistic, as it aimed at replacing one bureaucratic choice with another.

Each administrative option highlighted by the committee is a choice with specific benefits and drawbacks. Democratic principles dictate that the residents of FATA be allowed to choose among them. There is no clear indication of what exactly the people of FATA prefer. Some surveys do get quoted in support of a merger but what is left unstated is the efficacy of polling and the validity of the fundamental laws of sampling design in a war zone that grants limited access and a good chunk of whose population has been displaced. If political questions could be predicted by surveys, the US would have seen its first female president and the United Kingdom would not be grappling with Brexit.

The example of German unification is also instructive in the consequences of rushed political unions between contrasting governance systems

If fundamental rights and economic development can be achieved under all three options presented by the committee, why has a merger been favoured? The experience of Malakand and the provincially administered tribal areas are not happy ones, with FATA being on a different scale altogether. Some arguments marshalled in favor of a merger also ring hollow. Should FATA be merged simply because the agencies are not internally integrated? The isolation of the agencies was a colonial policy and in the present, when motorways are being constructed across the length and breadth of the country, certainly one that links Bajaur to South Waziristan is not beyond the capabilities of the state.

The fact that the residents of FATA are co-ethnics to the majority of KP’s population is a stronger argument, with even some allusions being made to the reunification of East and West Germany. This line of reasoning circles back to the manifesto of the National Awami Party, which called for the creation of linguistic provinces and reneged on that manifesto at the dissolution of One Unit in 1970.

While India was able to undercut regional rivalries by creating linguistic units, the state in Pakistan has been antithetical to the concept. There is no indication that this principle has been conceded in the case of FATA. The example of German unification is also instructive in the consequences of rushed political unions between contrasting governance systems. Due to the speed of the process and specific policy choices, East Germany has become an industrial hinterland with net migration to the erstwhile West, the scale of resources invested notwithstanding. For FATA, the prospect of ending up even more neglected than KP’s southern districts are quite real.

A rather more apt analogy would be that of Puerto Rico - an American territory that would benefit from a change in status. There have been calls on the territory for a closer relationship with the US but as the 51st state and not as an appendage to Florida, the closest state on the American mainland. There are clear advantages to being declared a province. Principal amongst them is a guaranteed share of the NFC pie. This share does not automatically accrue to FATA in case of a merger and proposals for ring fencing the budget are impractical - think South Punjab. However, new provinces ring alarm bells in Pakistan’s stymied polity since they raise the specter of a precedent for all the other three.

The third option is of a more viable autonomy, a continuation of FATA’s status but with the added accoutrements of an elected legislative council, assured budget and its own administrative apex. This third option is dismissed as being another Gilgit-Baltistan (incidentally another autonomous region that demands an upgrade) and discounts the possibility of negotiating a special dispensation, say GB+.

Yet FATA’s case is special; from its novel status in the constitution, to being subjected to inhuman colonial laws and economic neglect. The region has played a role in capturing for Pakistan what is now Azad Kashmir. It has a frontline status in the continuing war in Afghanistan. Its people have braved global terrorism and the indignity of mass displacement due to military operations. If any people have a claim for special dispensation it is the residents of FATA.

For some proponents of a merger the unwillingness to negotiate the best possible deal and acquiescence to what has been offered belies a sense of hapless desperation. The latest round of reforms have been framed as a closing opportunity to take advantage of a bureaucratic fiat, as if what is on offer is a privilege and not solemn rights. Although it might have been intended as a clever campaign tactic, the obfuscation of opposition-to-merger with opposition-to-reform has been a disservice to fostering a credible debate. A lack of debate denies the essence of any reform. Polities brought about as a result of violence often get trapped in cycles of violence whereas structures created by political action prove more responsive to their residents.

Consulting FATA residents and creating ownership of this process is essential. FATA evokes concern within Pakistan for a host of reasons, but beyond our borders these concerns are solely security-centric. Yet tinkering with FATA’s administrative status is not a panacea; after all, the region has the harshest administrative environment in the country. If regular administration were an effective bulwark against militancy, two of our provincial capitals would not have been globally known as eponyms of militant leadership councils. Tackling militancy requires changes in policy, usually in response to coherent and effective calls for change. The sit-in recently held in Islamabad proves that the people of FATA do not lack agency and are capable of voicing their preferences and negotiating peacefully. Their exclusion from what is surely a momentous decision about their future is criminal.