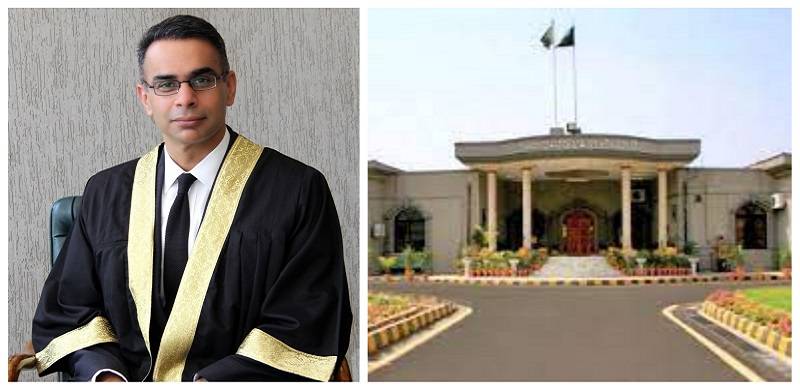

The Islamabad High Court (IHC) recently passed a judgement holding that all marriages where one or both parties are under the age of 18 are void ab initio - that is they have no legal status from the outset – thereby clarifying long standing legal ambiguities and gaps in the law.

While the applicability of the decision is limited to Islamabad, it is a significant development in jurisprudence on child marriage. Under prevailing federal child marriage legislation, the minimum age of marriage for girls is 16, not 18. Previous court judgments, relying on interpretations of Muslim personal law, have held that marriages of persons below the legal minimum age can nonetheless be valid if the parties have reached puberty.

It is laudable that the judgement affirms Pakistan’s international human rights obligations and upholds the principle that the legal framework must enforce the best interests of the child. Advocates against child marriage may want to hold their celebrations in abeyance, however, since the Court’s conclusions could have seriously adverse consequences on minors entering into these unions. In particular, the decision poses risks for young people who engage in consensual sexual activity and enter into self-arranged marriages.

Child marriage realities

The majority of child marriages in Pakistan involve adolescent girls between the ages of 15-18. According to UNICEF, 18% of women in Pakistan were married before they reached the age of 18 and 4% of women were married before the age of 15 (based on data collected from women aged 20-24). Although empirical data is scant, the nature of cases coming to courts tells us that many child marriages appear to be self-arranged, where the minor girl – typically an adolescent - has chosen to enter into the marriage. Interestingly, the matter on which the Islamabad High Court based its decision also involves a 15 year-old girl who asserted that she married of her free will and did not want to return to her parents’ home.

It should not be hard to see why self-arranged marriages among adolescents occur in our context. Sexual relations outside marriage are not only culturally proscribed but also criminalized. Therefore, the only culturally acceptable way for adolescents – especially adolescent girls – to engage in consensual sexual relations is to enter into a marriage.

Courts in Pakistan have given legal sanction to such marriages by relying on interpretations of Muslim personal law according to which marriage between persons who have reached puberty are valid. Courts have declared that underage marriages involving parties who have reached puberty, while illegal, are not automatically void.

The Islamabad High Court has now held that this reasoning is inconsistent with fundamental rights guarantees in Pakistan’s Constitution, Pakistan’s international human rights treaty obligations as well as prevailing criminal and civil laws. The IHC also found that previous court decisions were based on an incorrect understanding of the application of Shariah law in our legal framework.

Court’s reasoning

The Court refers to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international human rights treaty to which Pakistan is a party, to conclude that a child must be deemed to be a person under the age of 18. This is reinforced in other laws in Pakistan, including the Majority Act 1875 and the National Commission on the Rights of the Child Act.

The Court also refers to provisions in the criminal law enacted for the protection of children. Interpreting Section 375 of the Penal Code – which says that sex with a person under the age of 16 is rape with or without the child’s consent – as well as a Penal Code provision prohibiting sexual abuse of persons under the age of 18, the Court finds that there is no room in our legal framework to “deem permissible any act of a sexual nature involving a child even if it is with the explicit consent of such a child (emphasis added).”

The Court declares that marriage under Pakistan’s laws is a contract between two persons – the object of which is to legitimize sexual relations. It then concludes that a marriage contract cannot be valid if it involves a child since it is criminal for a child to engage in sexual relations - the very object of a marriage contract involving a child. Therefore, such a contract must be deemed void.

Criminalizing adolescent sexual behaviour

The Court has based its reasoning on the premise that consensual sexual activity by anyone under 18 – including between minors – is and should be prohibited. This line of reasoning is particularly dangerous for adolescents under the age of 18 who are in consensual sexual relations. It is inconsistent with the international human rights law principles that adolescent sexual behavior should not be criminalized. In fact, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the human rights body responsible for interpreting and monitoring the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child has clearly stated that non-exploitative, consensual sexual behavior among adolescents of similar ages should not be criminalized. The Committee has reaffirmed the call for decriminalization of adolescents who engage with one another in consensual sexual acts in its General Comment No. 24 on Children’s Right in Juvenile Justice.

In view of these principles of international human rights law, the statement by the Islamabad High Court that there is no room in our legal framework to “deem permissible any act of a sexual nature involving a child even if it is with the explicit consent of such a child” is inconsistent with the rights of the child.

The Penal Code provisions relied on by the Islamabad High Court are also inconsistent with these international human rights principles. Under the Penal Code provision on rape, an adolescent may be considered liable for rape even if they have consensual sexual relations with another adolescent under the age of 16. Similarly, under the Penal Code provision on child sexual abuse, an adolescent may be held criminally liable for child sexual abuse even when engaging in consensual sexual activities with another adolescent. These provisions, in making no distinction, between consensual and non-consensual sexual activity between adolescents, have the harmful effect of criminalizing young people for willingly engaging in sexual relations.

Evolving capacities of adolescents

The Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes that the capacities of children evolve as they grow older and legal frameworks should not assume that maturity levels remain static throughout childhood. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has noted that adolescence “is a unique defining stage of human development characterized by rapid brain development and physical growth, enhanced cognitive ability, onset of puberty and sexual awareness and newly emerging abilities, strengths and skills.” The Committee on the Rights of the Child has noted that while states should introduce minimum legal age limits, “the right of any child below that minimum age and able to demonstrate sufficient understanding to be entitled to give or refuse consent should be recognized.”

The Islamabad High Court’s judgment, which states that any person under 18 cannot be deemed to give valid consent to sexual activity runs against these international human rights principles. It is also insensitive to the social contexts under which many underage marriages occur.

While adolescent girls are often forced by parents to marry against their will, they may sometimes opt to enter into marriages for a range of reasons. They often marry when their pre-marital relationship is discovered by their parents. Young girls also sometimes enter into child marriages to escape a forced marriage arranged by their parents. A typical pattern in such cases is that criminal actions are often in itiated by parents to bring the girl back to their family, and their partner is charged with kidnapping and sometimes rape.

If all sexual conduct within the marriage is deemed child sexual abuse or rape, adolescent boys in consensual sexual relations – which they then seek to “legitimize” through marriage – could be convicted of sexual abuse or rape of a minor which is punishable by death or imprisonment for life. This is inconsistent with the fundamental human rights of young persons.

The Court’s proclamation that child marriages must be deemed void ab initio i.e., invalid from the outset, is also likely to leave many vulnerable young girls in a state of legal limbo. If they have a child from the union, what would its status be? Would she have any rights to maintenance? If her union is not recognized in the law, but the marriage is consummated, would she be subjected to even greater social stigma from her community and family members? Due to these complexities, the Center for Reproductive Rights has recommended that child marriage laws be enforced in a manner consistent with adolescents’ autonomy and vulnerabilities.

Protecting and empowering adolescents

In light of social realities, child marriages should be declared voidable, rather than void from the outset. Laws should be amended to set forth accessible procedures for such marriages to be annulled where one of the parties is under the age of 18. It is crucial that comprehensive and long-term child protection services be established, so that young people who have entered into a marriage are not restricted to two options: either return to their parents or stay with their “spouse.” In addition, Penal Code provisions on rape and child sexual abuse should be amended so that adolescents are not criminally liable to the stringent penalties set forth in these provisions for engaging in consensual sexual activity.

The Islamabad High Court’s judgement rightly affirms the primacy of the welfare of minors in the interpretation and application of laws. Our courts, law-makers and bureaucrats should also acknowledge that expanding the scope and power of criminal legislation is not the optimal approach for protection of children and young persons. Instead, policy measures should focus on protection and empowerment through implementation of welfare services and empowering reproductive health and education policies.

While the applicability of the decision is limited to Islamabad, it is a significant development in jurisprudence on child marriage. Under prevailing federal child marriage legislation, the minimum age of marriage for girls is 16, not 18. Previous court judgments, relying on interpretations of Muslim personal law, have held that marriages of persons below the legal minimum age can nonetheless be valid if the parties have reached puberty.

It is laudable that the judgement affirms Pakistan’s international human rights obligations and upholds the principle that the legal framework must enforce the best interests of the child. Advocates against child marriage may want to hold their celebrations in abeyance, however, since the Court’s conclusions could have seriously adverse consequences on minors entering into these unions. In particular, the decision poses risks for young people who engage in consensual sexual activity and enter into self-arranged marriages.

Child marriage realities

The majority of child marriages in Pakistan involve adolescent girls between the ages of 15-18. According to UNICEF, 18% of women in Pakistan were married before they reached the age of 18 and 4% of women were married before the age of 15 (based on data collected from women aged 20-24). Although empirical data is scant, the nature of cases coming to courts tells us that many child marriages appear to be self-arranged, where the minor girl – typically an adolescent - has chosen to enter into the marriage. Interestingly, the matter on which the Islamabad High Court based its decision also involves a 15 year-old girl who asserted that she married of her free will and did not want to return to her parents’ home.

It should not be hard to see why self-arranged marriages among adolescents occur in our context. Sexual relations outside marriage are not only culturally proscribed but also criminalized. Therefore, the only culturally acceptable way for adolescents – especially adolescent girls – to engage in consensual sexual relations is to enter into a marriage.

Courts in Pakistan have given legal sanction to such marriages by relying on interpretations of Muslim personal law according to which marriage between persons who have reached puberty are valid. Courts have declared that underage marriages involving parties who have reached puberty, while illegal, are not automatically void.

The Islamabad High Court has now held that this reasoning is inconsistent with fundamental rights guarantees in Pakistan’s Constitution, Pakistan’s international human rights treaty obligations as well as prevailing criminal and civil laws. The IHC also found that previous court decisions were based on an incorrect understanding of the application of Shariah law in our legal framework.

Court’s reasoning

The Court refers to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international human rights treaty to which Pakistan is a party, to conclude that a child must be deemed to be a person under the age of 18. This is reinforced in other laws in Pakistan, including the Majority Act 1875 and the National Commission on the Rights of the Child Act.

The Court also refers to provisions in the criminal law enacted for the protection of children. Interpreting Section 375 of the Penal Code – which says that sex with a person under the age of 16 is rape with or without the child’s consent – as well as a Penal Code provision prohibiting sexual abuse of persons under the age of 18, the Court finds that there is no room in our legal framework to “deem permissible any act of a sexual nature involving a child even if it is with the explicit consent of such a child (emphasis added).”

The Court declares that marriage under Pakistan’s laws is a contract between two persons – the object of which is to legitimize sexual relations. It then concludes that a marriage contract cannot be valid if it involves a child since it is criminal for a child to engage in sexual relations - the very object of a marriage contract involving a child. Therefore, such a contract must be deemed void.

Criminalizing adolescent sexual behaviour

The Court has based its reasoning on the premise that consensual sexual activity by anyone under 18 – including between minors – is and should be prohibited. This line of reasoning is particularly dangerous for adolescents under the age of 18 who are in consensual sexual relations. It is inconsistent with the international human rights law principles that adolescent sexual behavior should not be criminalized. In fact, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the human rights body responsible for interpreting and monitoring the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child has clearly stated that non-exploitative, consensual sexual behavior among adolescents of similar ages should not be criminalized. The Committee has reaffirmed the call for decriminalization of adolescents who engage with one another in consensual sexual acts in its General Comment No. 24 on Children’s Right in Juvenile Justice.

In view of these principles of international human rights law, the statement by the Islamabad High Court that there is no room in our legal framework to “deem permissible any act of a sexual nature involving a child even if it is with the explicit consent of such a child” is inconsistent with the rights of the child.

The Penal Code provisions relied on by the Islamabad High Court are also inconsistent with these international human rights principles. Under the Penal Code provision on rape, an adolescent may be considered liable for rape even if they have consensual sexual relations with another adolescent under the age of 16. Similarly, under the Penal Code provision on child sexual abuse, an adolescent may be held criminally liable for child sexual abuse even when engaging in consensual sexual activities with another adolescent. These provisions, in making no distinction, between consensual and non-consensual sexual activity between adolescents, have the harmful effect of criminalizing young people for willingly engaging in sexual relations.

In view of these principles of international human rights law, the statement by the Islamabad High Court that there is no room in our legal framework to “deem permissible any act of a sexual nature involving a child even if it is with the explicit consent of such a child” is inconsistent with the rights of the child.

Evolving capacities of adolescents

The Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes that the capacities of children evolve as they grow older and legal frameworks should not assume that maturity levels remain static throughout childhood. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has noted that adolescence “is a unique defining stage of human development characterized by rapid brain development and physical growth, enhanced cognitive ability, onset of puberty and sexual awareness and newly emerging abilities, strengths and skills.” The Committee on the Rights of the Child has noted that while states should introduce minimum legal age limits, “the right of any child below that minimum age and able to demonstrate sufficient understanding to be entitled to give or refuse consent should be recognized.”

The Islamabad High Court’s judgment, which states that any person under 18 cannot be deemed to give valid consent to sexual activity runs against these international human rights principles. It is also insensitive to the social contexts under which many underage marriages occur.

While adolescent girls are often forced by parents to marry against their will, they may sometimes opt to enter into marriages for a range of reasons. They often marry when their pre-marital relationship is discovered by their parents. Young girls also sometimes enter into child marriages to escape a forced marriage arranged by their parents. A typical pattern in such cases is that criminal actions are often in itiated by parents to bring the girl back to their family, and their partner is charged with kidnapping and sometimes rape.

If all sexual conduct within the marriage is deemed child sexual abuse or rape, adolescent boys in consensual sexual relations – which they then seek to “legitimize” through marriage – could be convicted of sexual abuse or rape of a minor which is punishable by death or imprisonment for life. This is inconsistent with the fundamental human rights of young persons.

The Court’s proclamation that child marriages must be deemed void ab initio i.e., invalid from the outset, is also likely to leave many vulnerable young girls in a state of legal limbo. If they have a child from the union, what would its status be? Would she have any rights to maintenance? If her union is not recognized in the law, but the marriage is consummated, would she be subjected to even greater social stigma from her community and family members? Due to these complexities, the Center for Reproductive Rights has recommended that child marriage laws be enforced in a manner consistent with adolescents’ autonomy and vulnerabilities.

Protecting and empowering adolescents

In light of social realities, child marriages should be declared voidable, rather than void from the outset. Laws should be amended to set forth accessible procedures for such marriages to be annulled where one of the parties is under the age of 18. It is crucial that comprehensive and long-term child protection services be established, so that young people who have entered into a marriage are not restricted to two options: either return to their parents or stay with their “spouse.” In addition, Penal Code provisions on rape and child sexual abuse should be amended so that adolescents are not criminally liable to the stringent penalties set forth in these provisions for engaging in consensual sexual activity.

The Islamabad High Court’s judgement rightly affirms the primacy of the welfare of minors in the interpretation and application of laws. Our courts, law-makers and bureaucrats should also acknowledge that expanding the scope and power of criminal legislation is not the optimal approach for protection of children and young persons. Instead, policy measures should focus on protection and empowerment through implementation of welfare services and empowering reproductive health and education policies.