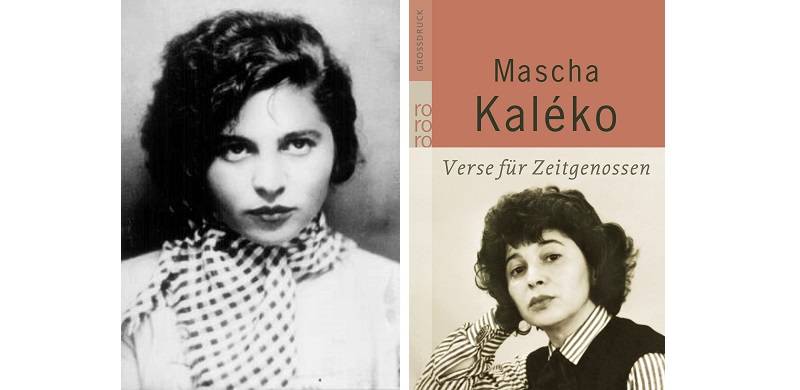

In literature and associated narratives, females often carry the otherness and foreignness in society. The poetry of Mascha Kaléko is an example of it: born to Jewish-German parents, she suffered from the otherness in German society. Though well-recognised now among German poets, she is hardly known in other parts of the world, even though her poetry resonates with marginalised and the Other. In the context of Pakistan, especially, her poetry can contribute new avenues to explore the experience of otherness and alienation in society. Her experience of otherness as a religious and ethnic other while sharing the same nationhood is similar to the minorities living in Pakistan. About this estrangement, Urdu literature is often silent and aloof from this otherness of religion and ethnicity. The sense of pain, grief, loss, and insecurity in society magnifies among minority communities but Urdu literature is more often silent about it.

Reading Kaléko’s poetry in the loneliness of Leipzig was an experience of living in the turbulent times of her writings. I can resonate with her experience of being Other in my own country and now in another one. This constant foreignness is rather a heavy baggage that I carry in my soul: the change of places has made me aware of that and her writings made me more aware of it.

(Song of Foreignness – trans. Timothy Adés)

How society treats the other, whether based on ethnicity, religion, caste, or social class, stays undocumented in the Urdu literature. Reading Kaléko, I found that even loneliness only makes sense by the presence of the other.

(The Much-Praised Solitude, 1971 – trans. Unknown)

This articulation of alienation and loneliness is not about romance gone wrong, a thirst for bodily desire, or the inclusion of some Western agenda in the purity of Urdu literature, but rather the assertion of a voice not heard for centuries that finally asketh ear to listen to its cries. Someone has to put in words the suffering of the centuries by the sons and daughters of this land.

Kaléko lives through the miseries of her times and collects together the yearning of a becoming in which lies the seed of change.

(No Making it New – trans. Timothy Adés)

As I read Kaléko, I cannot help but think about her relevance for the Urdu literature that stays isolated from the presence of the Other and hence deprived of the richness that comes through in dialogue with the otherness of the other. Experimenting with literature from other parts of the world is in itself a process of exploring the otherness and embracing it, which nurtures awareness of difference, acceptance, and living together in disagreement. Even though one might not be able to see the Other, in their otherness the effort is worthwhile to increase our understanding of who we are.

(The “Possible” – trans. Unknown, 1973)

Reading Kaléko’s poetry in the loneliness of Leipzig was an experience of living in the turbulent times of her writings. I can resonate with her experience of being Other in my own country and now in another one. This constant foreignness is rather a heavy baggage that I carry in my soul: the change of places has made me aware of that and her writings made me more aware of it.

Foreignness is too cold a gown:

Too tight, the collar’s fit:

And in my bag from town to town

Through life I’ve carried it.

(Song of Foreignness – trans. Timothy Adés)

How society treats the other, whether based on ethnicity, religion, caste, or social class, stays undocumented in the Urdu literature. Reading Kaléko, I found that even loneliness only makes sense by the presence of the other.

How sweet it is to be alone!

Provided that, of course, there is

Someone to whom one can say this:

“How sweet it is to be alone!”

(The Much-Praised Solitude, 1971 – trans. Unknown)

This articulation of alienation and loneliness is not about romance gone wrong, a thirst for bodily desire, or the inclusion of some Western agenda in the purity of Urdu literature, but rather the assertion of a voice not heard for centuries that finally asketh ear to listen to its cries. Someone has to put in words the suffering of the centuries by the sons and daughters of this land.

Kaléko lives through the miseries of her times and collects together the yearning of a becoming in which lies the seed of change.

I sing the way the birdy sings,

Or would sing, it may be,

If he lived in the thick of things,

An alien like me

(No Making it New – trans. Timothy Adés)

As I read Kaléko, I cannot help but think about her relevance for the Urdu literature that stays isolated from the presence of the Other and hence deprived of the richness that comes through in dialogue with the otherness of the other. Experimenting with literature from other parts of the world is in itself a process of exploring the otherness and embracing it, which nurtures awareness of difference, acceptance, and living together in disagreement. Even though one might not be able to see the Other, in their otherness the effort is worthwhile to increase our understanding of who we are.

I struggle with the angels and devils, that’s true,

Was nurtured by fire and guided by light,

And even impossible things I could do,

But what is possible I cannot get right.

(The “Possible” – trans. Unknown, 1973)