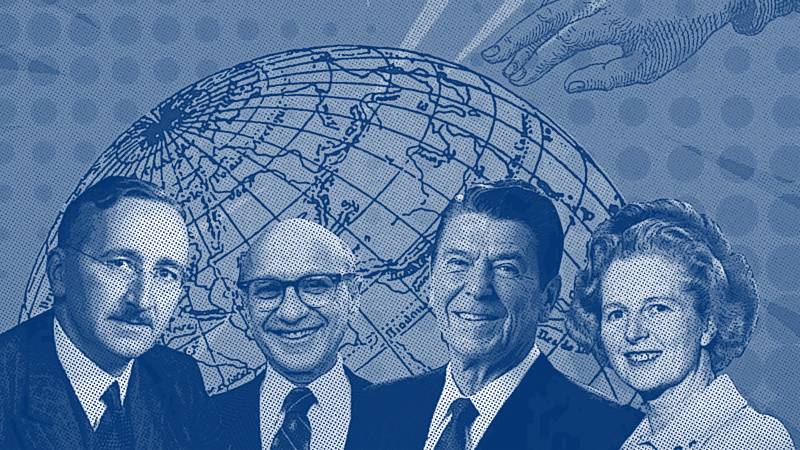

Economics emerged on the basis of the work done by political philosophers as societies began to emerge from feudalism with the advent of industrial capitalism. This early Economics reflected the conditions and problems of the time, such as the trade cycle, and the instability created by external imbalances. But, at the same time, the failings of capitalism also began to be noticed in the emergence of a poverty-stricken industrial working class, the use of child labour and the abominable living conditions of the poor. These contradictions were not glossed over by the political philosophers and healthy debates were conducted between the interventionists and non-interventionists. Since 1980, similar contradictory trends have emerged once again, if anything with greater intensity. But most neoliberal ideas and their protagonists have utterly failed to grasp the havoc their policy prescriptions have caused rich and poor countries alike.

Since the year 2000, the UN has adopted first the MDGs, the Millennium Development Goals and, second, in 2015 the SDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals with aim of ending extreme poverty and safeguarding the environment. Neoliberals tend to regard these goals with disdain and question their legitimacy by sniping from the sidelines. Ruling elites in most countries have joined in the sniping, continuing to sing the praises of the private sector and markets. Today, far from making progress towards realizing these goals, even previous gains are in the process of being reversed – because preserving the status quo reigns supreme in this socio-political matrix, more or less across the world.

But this does not mean that a framework for solutions does not exist, as we explore in the remaining part of this article. Above all, it is morally indefensible that adherence to arbitrarily constructed man-made formulas, for example the size and sustainability of debt, should take precedence over the far more urgent challenges of global warming, the precarious state of the environment and the blighted lives of the poor.

Poverty, both absolute and relative, has been a starkly visible, disheartening feature of all human societies from the earliest days. Even so, very little has been done to deal with it – in the developing countries in terms of absolute poverty and in the developed in terms of relative poverty. Indeed, there has been a tendency to accept it as something in the very nature of human society about which nothing, or almost nothing, can be done at the practical policy level other than charity and philanthropy. In the 19th century, with the advent of industrial capitalism, the gap between rich and poor widened to a chasm and was reflected in a wide range of writings concerned with social issues and problems.

Instead of relying on the questionable, indeed, falsifiable, nostrums of neoliberal ideology that favour the ruling elites in most countries, the world needs to make a commitment today to end the suffering of the poor

Since about the mid-1990s similar trends have become evident once more in both developing and developed countries and once again individuals and organisations have raised their voices underlying the urgency and gravity of poverty. Over the last 50 years or so it has gradually been accepted that the continuation of poverty is simply unacceptable. This is so because poverty is a colossal waste for society when millions of its members are unable to fulfil their potential simply because they are poor and are therefore unable to participate meaningfully in the productive activities of that society. Today, such losses cannot be justified either morally or practically.

In his book, The End of Poverty: How We Can Make It Happen In Our Lifetime published in 2005, the renowned development economist Jeffrey Sachs stated that 8 million people die each year because they were too poor to stay alive.

Moreover, “they died namelessly without public comment. Most people are unaware of the daily struggles for survival and of the vast numbers of impoverished people around the world who lose that struggle every day”. In 1930 Keynes pondered the dire impact of the Great Depression on the poor of Britain. He envisioned the end of poverty towards the end of the 20th century on the back of the dramatic march of science and technology. Sachs urged us in 2005 to end poverty not by some distant date in the future but in our time, i.e. by 2025.

Instead of relying on the questionable, indeed, falsifiable, nostrums of neoliberal ideology that favour the ruling elites in most countries, the world needs to make a commitment today to end the suffering of the poor, to build, on the basis of our common humanity, a world in which basic health services and good quality education are available to all and the wanton destruction of the environment becomes a thing of the past. At the Stockholm Resilience Centre experts have concluded that the world’s life support systems have so far remained manageable. But, once the boundaries are breached, everything will become much more extreme and unpredictable. The Centre’s assessment is that today in 2023 we are very close to breaching those boundaries. Time is not on our side. Today, the world needs an entirely different economics to confront these challenges.

Side-by-side with that new commitment, two massive intellectual challenges also need to be resolved to convert the collective desire of humanity that poverty cannot be allowed to continue are: one, the irrationality that prevails with regard to the role of markets in our lives and, two, the belief that taxes are some kind of evil. Instead of giving markets a quasi-divine status, as neoliberalism does, we should realize that markets ultimately are a human construct. They perform a useful function by facilitating the buying and selling of goods and services. But that does not mean that markets can intrude into every nook and cranny of our existence.

There are moral limits to markets that as human beings we should not tolerate. In the past, slavery was one such consequence of a belief in markets – that human beings could be bought and sold. Today, the selling of kidneys and/or other body parts, while it takes place unofficially, is illegal across the world. Similarly, children or, indeed, other members of the family cannot be sold however dire the circumstances.

Moreover, can anyone justify putting a monetary value on sympathy, thoughtfulness and loyalty? Societies do not function merely on the basis of what can be bought and sold or on the profit motive; they function as much on the basis of the values mentioned here. Hence, in the end, if markets fail to deliver the urgent needs of society, for instance, low-cost housing, should we just shrug our shoulders at its inevitability, or, as empathetic human beings ask the government to intervene?

Taxes are another bugbear, especially for the better off. And the media and academics have been complicit in sustaining this bugbear. But without taxes the fight against poverty cannot even begin, because the fight, like fighting a war, requires resources, both financial and human. In neoliberal ideology, taxes are either grotesquely described as ‘theft’ by the state/government, or widely regarded as a disincentive to the enterprise of individuals and/or corporate bodies.

Hence, across the world there is a constant clamour for taxes to be cut or reduced. But what are taxes in reality? Taxes are simply a levy that society itself collects, via the state, from the individuals and corporate bodies that make things and offer services in that society – create value in terms of 19th century parlance. It is not difficult to realise that it is society as a whole that enables individuals and enterprises to create value in the first place. They are certainly not theft in any meaningful sense of the word. They are meant, on the contrary, to make society more productive by maintaining its infrastructure and institutions, including social safety nets, without which society would descend into chaos. Yes, some states can be inefficient and others can be wasteful, but the principle of levying taxes does not thereby get negated in the process.

A new social contract is needed to rebuild societies, to overcome despair, to give the poor a fighting chance to survive and bring up their children in dignity and for ruling elites to stop looking for scapegoats for their own failures

There is today a belief that there should be no, or minimal, taxes with the state only providing for defence, policing and courts with everything else left to private investment and the markets. How would such a society deal with social justice? Above all else, the evidence indicates that while investments are undertaken for profit the level of taxation is not the only disincentive. Investments are undertaken on the basis of a host of considerations – size of market, the prevailing physical and institutional infrastructure and the availability of the needed human resources to fructify those investments and, yes, taxes as a distant fourth consideration. Had this not been so the whole of global economic activity would have migrated to the world’s many tax havens.

Since the 1980s the world economy has lurched from one crisis to another and thrown up new and more urgent challenges for governments. This article has outlined the need to consign the nostrums of neoliberals to history before they do further damage, not just in the countries mentioned at the beginning, but across the world where despair and helplessness now reign. A new social contract is needed to rebuild societies, to overcome despair, to give the poor a fighting chance to survive and bring up their children in dignity and for ruling elites to stop looking for scapegoats for their own failures. A world in which the 10 richest individuals have as much wealth as 40 per cent of the world’s population cannot be a just world. It cannot even be an efficient and productive world. But today we no longer live in ignorance.

We know what is wrong and how it can be fixed and it will not be by entrusting our futures to markets and private investors. What we need instead are energy and emotional intelligence so that the fine words in articles, books and speeches in international forums can be turned into practical action that directly addresses poverty, inequality and the looming catastrophe of global warming.