Hamas is a militant Islamist outfit that controls Gaza, a narrow strip of land bordering Israel and Egypt. Gaza is part of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) which also includes enclaves in an area referred to as the West Bank. Under an agreement in the early 1990s, Israel allowed the Palestinians in Gaza and West Bank ‘self-rule’ as a means to mitigate the decades-old violence between Palestinians and the State of Israel. Much of the West Bank is administrated by Fatah, the largest faction of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO). The PLO was formed in 1964 as an alliance of various militant Palestinian groups looking to undo the 1948 creation of Israel on land that, till 1948, had an Arab majority and was called Palestine.

PLO/Fatah is a secular outfit. It rose as a left-leaning armed movement against Israel. In the 1970s, Fatah was accepted by most Muslim-majority countries and communist states as the main representative of the Palestinian people. From the 1980s onwards, its leader Yasser Arafat, gradually began to rollback Fatah’s militancy. In 1993, Fatah agreed to give up armed struggle, and recognise the State of Israel in exchange for self-rule of Palestinians in Gaza and West Bank.

Hamas was created in December 1987. However, according to propaganda literature produced by Hamas, it is a continuation of armed struggles against the British in the 1930s, and then the Zionists who had been allotted land by the British in Palestine to create a country for Jewish people. As a tactic, the Palestinians had agreed to work closely with the British authorities. This is why the British initially hesitated in allowing the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. But the British capitulated due the militancy and terror attacks against it by a far-right Zionist outfit, Irgun. Even though there is evidence that a faction of the Muslim Brotherhood — an Islamist outfit formed in Egypt in late 1920s — too was involved in anti-British activities in Palestine, compared to Irgun, the Brotherhood’s actions were diminutive. As mentioned, to neutralise forces looking to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine, most Palestinian groups had agreed to support the British.

Irgun used bombings and assassinations to put pressure on the British. Arabs, too, were attacked. In 1946, Irgun blew up a hotel in Jerusalem, killing 92 people. In 1947, it raided an Arab village and killed over a 100 people. After Israel’s eventual creation in 1948, Irgun members joined the new country’s armed forces. Right-wing Zionist militancy and terrorism were major contributors in the creation of Israel.

Gaza at the time was under Egypt’s control, even though it was largely populated by Palestinian refugees escaping the first Arab-Israel war in 1948. The Arab states were defeated in that war. The Muslim Brotherhood managed to establish a following among the Palestinians in Gaza. A Brotherhood member was elected mayor. In 1952, the Egyptian monarch was overthrown in a military coup and Egypt was declared a republic. The officers who organised the coup had participated in the 1948 war. They blamed the monarchy for the defeat and managed to cultivate support among the Egyptian people. The Brotherhood supported the coup until the new regime began being headed by Gamal Abdel Nasser who was a staunch Arab nationalist.

A Brotherhood activist, incensed by Nasser’s secular disposition, tried to assassinate him. Nasser launched a crackdown against the Brotherhood and also sent armed men to oust the Brotherhood from Gaza. The situation in Gaza remained volatile due to clashes with Brotherhood militants, and Nasser’s plan to infiltrate Israel from Gaza. In 1956, Israeli, French and British forces attacked Egypt. They wanted to overthrow Nasser and take control of the Suez Canal. Nasser had nationalised the canal, thus hurting the economic interests and investments of the mentioned countries. A resistance movement against Israeli, French and British forces was launched in Gaza. But incensed by Nasser’s actions against the Brotherhood, the organisation did not participate in that movement.

The Brotherhood was severely repressed in Egypt. It was then ousted from Gaza. Nasser was aided by Arab states and even the U.S. in repelling the Israeli, British and French attack. He began being hailed as a ‘hero’ in the Muslim world.

Meanwhile, Yasser Arafat formed the Fatah in 1959 and in 1964 merged it with the newly formed PLO. The Brotherhood went underground and lay low until Nasser’s death in 1970. In 1967, when Israel decimated the combined forces of Egypt and Syria, Israel occupied Gaza. PLO factions were in the forefront of resisting the occupation.

In 1978, four years after yet another war with Israel, Nasser’s successor Anwar Sadat agreed to stop claiming Gaza as part of Egypt and signed a peace agreement with Israel. PLO was livid. It had often used Gaza to launch attacks against Israel. By 1973, however, when Sadat broke ties with the Soviet Union and was rewarded with financial aid by the US and Saudi Arabia, PLO’s influence had begun to weaken in Gaza. Then, in 1978, Sadat recognised the State of Israel. He signed a deal with Israeli PM Menachem Begin (a former member of the notorious Irgun), that established peace between Egypt and Israel and looked to grant the Palestinians self-rule in Gaza and West Bank. The Muslim Brotherhood tried to revive itself in Gaza but was constantly pushed back by PLO/Fatah fighters.

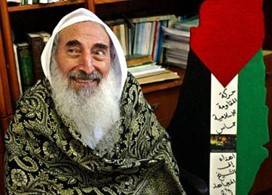

However, tacitly backed by Saudi Arabia and Israel, a Palestinian sympathiser of the Brotherhood in Gaza set out to rebuild support for the Brotherhood by launching charity organisations. His name was Shaikh Yasin. A Palestinian ‘imam,’ he had opposed the ‘secular’ Arab nationalist regimes and was also opposed to the PLO. Yasin formed his own organisation in Gaza: Al-Mujamma al-Islami. In 1979, the Mujamma was recognised by Israel and Egypt as a ‘legitimate’ Palestinian organisation.

The aim was to weaken Palestinian nationalism championed by PLO and encourage an Islamist alternative. In 1980, as a show of strength in Gaza, Mujamma attacked the offices of an organisation that had elected a communist. It then went on a rampage, attacking cinemas, restaurants, coffee houses and bars in Gaza. The attacks were ‘allowed’ (and not stopped) by the Israelis. Nor were Mujamma’s attacks against Fatah. The Israelis gleefully looked on as Yasin aimed to ‘clean’ Gaza and rid it of communism, secularism and Palestinian nationalism. He accused the nationalists of being ‘against Islam.’

Convinced that Mujamma had greatly weakened Fatah/PLO in Gaza, Israel decided to arrest Yasin in 1984 after finding a stash of firearms in a mosque. Ironically, the weapons were stockpiled to further damage the Fatah. Yasin had been facing accusations of being ‘Israel’s man’, but his arrest began to improve his reputation. Only 50 Brotherhood members were left in Gaza in the late 1960s. But Yasin, through his charity organisations and lectures in mosques, managed to slowly draw the support of the people of Gaza and build an impressive following. His organisation greatly reduced the influence of PLO/Fatah in Gaza.

In 1987, anti-Israel protests erupted in Gaza and West Bank. The protests were spontaneous and did not have a central leader or organisation. PLO/Fatah was already exhausted by almost three decades of armed resistance. It was also severely weakened by Mujamma. During the uprising, the Mujamma formed a militant wing called Majd which soon evolved into becoming Hamas. Hamas took over the leadership of the uprising (the Intifada).

Arafat’s Fatah agreed to recognise the State of Israel and take a more ‘peaceful route’ to establish peace in the region. Fatah won some concessions from Israel, and the Palestinians were allowed self-rule in Gaza and the West Bank. In 1996, an election was held in these regions (PNA) to form a Palestinian government. Hamas rejected the Fatah-Israel accord and boycotted the election. Arafat’s Fatah swept the polls with 89.82 percent of the total vote. The far-left Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine came second with 10.18 percent. The first PNA Legislative Council was thus packed with Fatah members.

Fatah established some normalcy, especially in West Bank. It continued negotiating with Israel for more freedoms for the Palestinian people. But the situation in Gaza remained tense.

In 2005, a presidential election saw Fatah candidate Mahmoud Abbas win. He received 67.38 percent of the votes. The election was boycotted by Hamas. In September 2005, Israel agreed to ‘disengage’ its forces from Gaza and the West Bank.

A new election for the legislative assembly was announced by Abbas, a full decade after the 1996 polls. This time Hamas decided to contest. It had firmly established itself in Gaza, operating charity services and armed militant wings. It continued to refuse recognising the State of Israel. In the 2006 legislative election, Hamas ran past Fatah by receiving 44.45 percent of the total vote to Fatah’s 41.43 percent. It won 74 seats to Fatah’s 45. Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh formed the new government with himself as prime minister. Israel, US and Western powers refused to work with the Hamas regime unless it recognised Israel and follow the agreements signed by the former Fatah government and Israel. Hamas declined and therefore faced economic sanctions. However, the Hamas regime was aided by Iran, Syria and Qatar.

Clashes broke out between Fatah fighters and Hamas militants. Fatah was expelled from Gaza. In 2007, President Abbas declared a state of emergency. He dismissed Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh and replaced him with Salman Fayyad and then with a Fatah member Rami Hamdallah. After the dismissal of the Hamas regime, the PNA was de facto divided into two entities: The Hamas-controlled Gaza and the Fatah-governed West Bank. The Fatah regime in West Bank was recognised by the United Nations as the only legitimate government in PNA.

Conclusions

- Hamas has roots in Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood (MB). Even though Hamas literature defines its current anti-Israel militancy as a continuation of MB’s anti-Zionist activism which first emerged in the 1930s, the fact is this activism greatly eroded between the early 1950s and late 1980s. During this period, MB was more focused on challenging secular Arab nationalist regimes and was aided by Saudi Arabia for this purpose. Till the late 1980s, anti-Israel militancy was largely the domain of PLO and various leftist Palestinian factions.

- The immediate roots of Hamas reside in the Palestinian ‘imam’ Shiekh Yasin’s Al-Mujamma al-Islami. This organisation was formed by Yasin in 1979. Mujamma’s presence in Gaza and West Bank was recognised and even bolstered by Israel to neutralise the influence of PLO. The Israelis believed that the Islamisation of the Palestinian nationalist movement would work in Israel’s favour because Israel was aiding the U.K. and the US in mitigating the spread of ‘communist’ ideas in the Muslim world, and financing anti-communist ulema and parties. In the 1980s, Israel also embarked on a mission to facilitate the CIA in providing funds and weapons to anti-Soviet Afghan jihadists in Afghanistan.

- However, in 1984, Yasin was arrested by Israeli authorities for stockpiling weapons in a mosque. Ironically, the weapons were meant to be used against the PLO, even though Yasin had already begun to speak about a war against non-Muslims in the region. It is likely that the arrest was made to remind Yasin that his power depended on Israeli support. But by then, Yasin had used the charity services and mosques run by Mujamma to build a large following for himself, especially in Gaza.

- The Mujamma evolved into becoming Hamas during the 1987 anti-Israel uprising in Gaza and West Bank.

- Hamas rejected the ‘peace agreement’ between Israel and Fatah in 1993. The agreement granted self-rule to Palestinians in West Bank and Gaza (which now came under Palestine National Authority or PNA).

- Hamas boycotted the first legislative elections in PNA, held in 1996. Three years earlier, Fatah’s Yasser Arafat was already appointed as President of PNA. Promising peace and self-rule, Fatah swept the polls. Fatah, once a leading anti-Israel militant group, also agreed to rollback its militancy and agree to recognise the State of Israel.

- Hamas began to send suicide bombers into Israel. The attacks were often followed by Israeli reprisals in the form of aerial bombings of Gaza. Despite deteriorating relations between the Fatah government and Hamas, Arafat convinced Hamas to join his government, believing that this would soften the radicalism of Hamas. In 2004, Arafat passed away. The same year Sheikh Yasin was killed by an Israeli missile.

- In 2005, Fatah’s Mahmoud Abbas won that year’s presidential election. The election was boycotted by Hamas. But Abbas was successful in persuading Hamas to contest the 2006 legislative election.

- The election was won by Hamas on the strength of its charity works and display of muscle against Israel. Hamas formed the new government but refused to recognise the State of Israel. Western powers halted all aid to Palestine.

- When Fatah refused to join the Hamas government, clashes broke out in Gaza and West Bank between the two parties. Dozens perished in the fighting which also saw Hamas firing into a large pro-Fatah rally in Gaza. Hamas was able to almost completely oust Fatah from Gaza.

- Gaza fell in the hands of Hamas, whereas Fatah remained in power in West Bank.

- In 2012, the main political leadership of Hamas settled in Qatar, after which it declared its support for opposition groups in an uprising in Syria against the ruling Ba’ath regime. This strained Hamas’ ties with Syria and Iran. Iran greatly reduced its aid to Hamas.

- Hamas’ position was further weakened when, in 2013, the Muslim Brotherhood government was overthrown in Egypt by the military. Lack of support and aid from Iran, Syria and now Egypt, and attacks by Israel, made living conditions unbearable in Gaza. Hamas began to heavily tax the already impoverished residents of Gaza. This triggered anti-Hamas protests and strikes.

- However, funding from Qatar somewhat improved the conditions and Hamas was able to retain its control of Gaza.

- Hamas attacks against targets in Israel (through missiles and suicide bombings) and the equally brutal Israeli reprisals have continued to intensify, especially ever since the Israeli government began being headed by far-right Zionists.

- The Israeli far-right is now hell-bent on using military means alone to ‘settle the Palestine question.’ Ironically, this mindset is being bolstered by the increasing militancy of Hamas whose attacks against Israeli targets have witnessed a manifold increase.

- As Hamas missiles strike major Israeli cities, Gaza continues to face Israeli bombings. Hundreds died recently in Israel in Hamas’ ground and missile attacks, and thousands perished in Gaza when Israeli jets once again flattened the area.

- Both combatants — the far-right Israeli regime and the Islamist Hamas — are also embroiled in a vicious propaganda war on social media. It is as if, both are looking to trigger a widespread conflict in the Middle East.

Extremes often burn themselves out, but not before setting fire to as much of the world as they can touch. This seems to be the route Hamas and the Israeli far-right have decided to take.