In April 1952, Jawaharlal Nehru ascended a viewing tower in the middle of a dusty construction site at the foothills of the Himalayas. From this heightened vantage, India’s first Prime Minister surveyed the foundations of Chandigarh, a new capital for Punjab State. Nehru welcomed the city as “symbolic of the freedom of India, unfettered by the traditions of the past, an expression of the nation’s faith in the future.” Organised on a grid system with straight roadways and carefully zoned sectors, Chandigarh was designed to inculcate new ways of living in a young, post-colonial republic. The past was not to be abolished, however, but safely contained. One of the most important containers would be the Government Museum and Art Gallery, nestled into a leafy corner of Sector 20.

Like Chandigarh’s iconic Palace of Assembly and High Court, the Museum was designed by the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. It shares with much of the city’s architecture a blocky, brutalist feel, though the concrete frame is softened here by exterior walls of warm, red brick. Protected inside the structure is a trove of archaeological and art historical artefacts that came to Chandigarh from the Lahore Museum, or Ajaib Ghar (‘House of Wonders’), some 250 kilometres away. Established in 1865, the Lahore Museum was a product of British colonialism in Punjab. Its display cases exhibited objects excavated from archaeological sites in the region as well as local art and craft items for public appreciation. The Ajaib Ghar was designed by the great Lahori architect Sir Ganga Ram in the Indo-Saracenic style. Its richly decorated exterior and multiple domes present a stark contrast to the sharp angles and austere facade of the Chandigarh Museum, even if it too was constructed with red brick.

The 1947 Partition of colonial India was a partition of territory but also of people and objects. The uncertainty and upheaval that marked the mass population transfers of 1947 was not, however, reflected in the fate of the Ajaib Ghar collections. Negotiations between the new states of India and Pakistan in 1948 resulted in some 40% of its stores being transferred to India, stationed variously in Amritsar, Shimla and Patiala before eventually arriving in Chandigarh. Le Corbusier’s Government Museum opened in 1968.

At the heart of the relocated collection is an extraordinary reserve of 627 Gandharan sculptures. A large gallery on Level 2 is filled with stone-carved reliefs, pieces of sculpted bodies, architectural fragments and much more. Gandhara, a Buddhist kingdom that existed from the first century BCE to fifth century CE, was located along the modern-day border between north-west Pakistan and Afghanistan. Its centres were Peshawar and Taxila. Gandharan art is distinguished in the subcontinent by its display of Hellenistic influences. Alexander the Great’s 4th-century BC military campaigns in India left in their wake a succession of Indo-Greek kings who maintained links with the Mediterranean world. Gandhara’s culture reflected its place at the crossroads of India, Asia and the West.

The identification of Gandharan sites by British soldiers and administrators in the mid-nineteenth century led to a boom in excavations. Colonial archaeologists fed a demand for these syncretic sculptures amongst European collectors and produced substantial deposits for museums in Lahore and Calcutta. The subcontinent’s Buddhist heritage – which included Gandhara but also the kingdom of Magadha and the memory of Ashoka – was woven easily into postcolonial India’s national narrative. It was projected by Nehru and others as a rooted, ethical system that would help guide a new secular state. But Buddhism also played a surprising role in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Scholars like Ananya Kabir and Andrew Amstutz have shown how ancient Buddhist centres within Pakistan’s borders were upheld in the decades after independence as evidence of the country’s status as a ‘sacred’ land. A Buddhist inheritance connected Pakistan’s eastern and western wings via Taxila and Mainamati and provided useful fodder for cultural diplomacy with Southeast Asia as well as Europe.

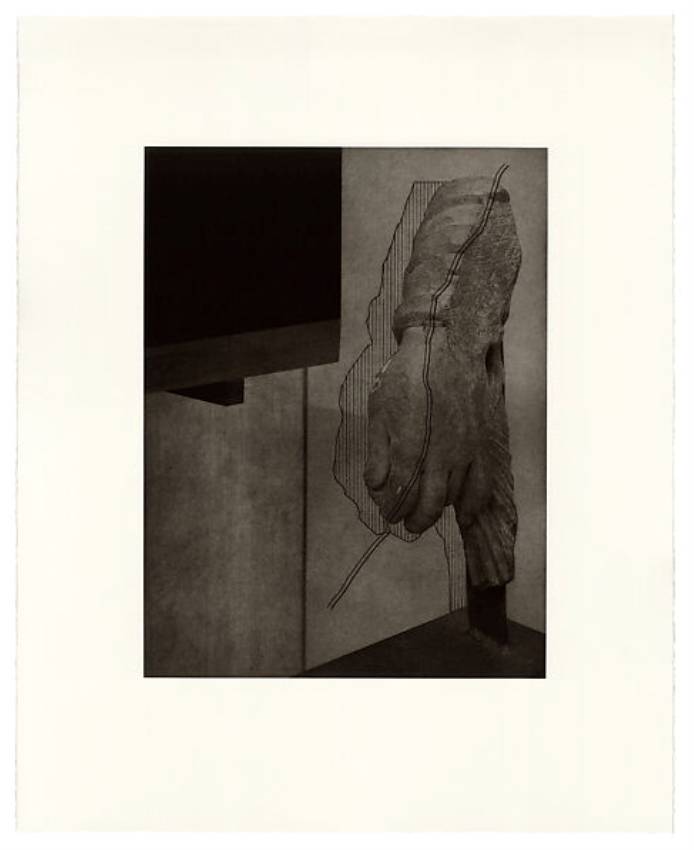

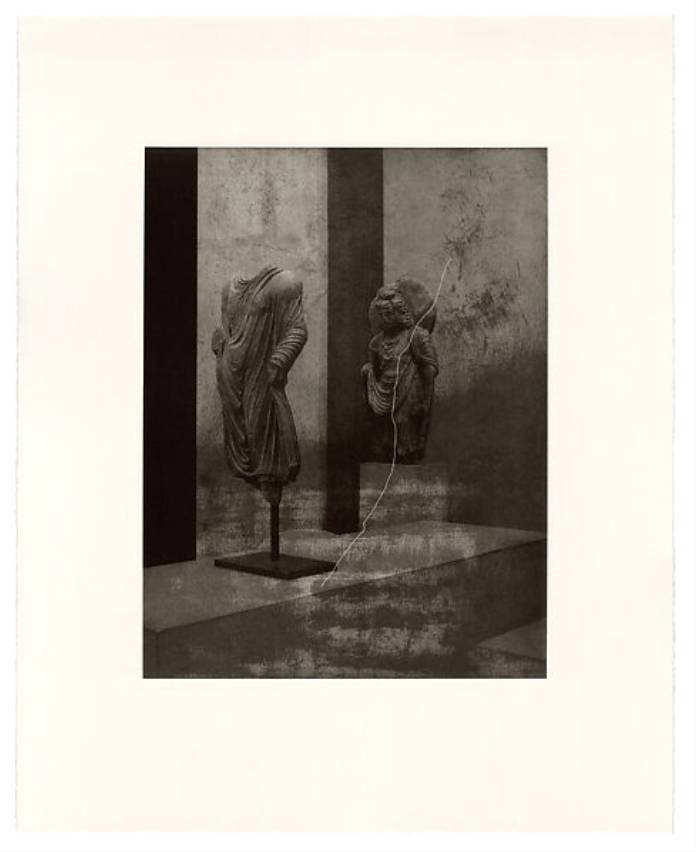

A series of prints by the artist Seher Shah returns to this history and unsettles its easy integration into the present. Titled ‘Argument from Silence’ (2019), Shah’s portfolio is composed of ten polymer photogravures based on images of the Chandigarh Museum taken in collaboration with the photographer Randhir Singh. They depict the fragmented bodies of the Level 2 gallery: torsos without heads, hands without arms, stucco busts balanced on plinths. The sense of absence or partiality is accelerated by Shah’s accentuation of negative spaces: walls, corners and other crevices are soaked in a deep black ink. In other prints, there are lines cut across the image or assembled into a grid to suggest calculation or measurement.

An ‘argument from silence’ is a form of reasoning that makes a contention based on absence. In historical writing, it names an argument based on a lack of evidence. It is an analysis of what has been left unsaid. The Chandigarh Museum displays artefacts from the past, but it is also a repository of histories that are not named – histories that are foundational to the assembly of objects in the gallery and to the very coming together of the museum. Writing about the prints, Shah explains that she wanted to explore the “underlying violence in relationships between object, history and architecture.” This is a general theme that could provide a window into many museum collections. But in Chandigarh, it identifies the Government Museum as an unacknowledged and powerful monument to the partition of India.

Glasgow, where ‘Argument from Silence’ was recently on display as part of a Shah retrospective at the Glasgow Print Studio, has at least one significant Gandhara connection. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, the last Director of the Archaeological Survey of India (1944-48), was born in the city in 1890. Wheeler established a field-training school in Taxila, the Gandharan capital, in 1944 and was involved in excavations of the Bhir Mound, some of the site’s oldest ruins. Appointed as Archaeological Advisor to the new Government of Pakistan in 1948, Wheeler was closely engaged with questions of patrimony in the state’s early years, helping to restructure museum collections and mediating some of the disputes with India over objects and artefacts.

The more direct rationale for setting Shah’s retrospective in Scotland is her long relationship with the Glasgow Print Studio. The ‘Argument from Silence’ portfolio, alongside several of the artist’s other projects, were made here, under the guidance of master printers Alistair Gow and Stuart Duffin. The exhibition foregrounds this relationship between artwork, artist and studio, animating another history latent in Shah’s prints: a tradition of craftsmanship, of engaged and passionate work, connecting the printmaker’s studio across space and time to the sculptor’s workshop. A line is forged from Shah, preparing her copper plate for printing, to the Gandharan artist, working out the folds on the Buddha’s sleeve.

In between the sculptor’s chisel and the artist’s etching needle is the archaeologist’s brush, the architect’s ruler and, crucially, the British cartographer’s pen. Shah’s retrospective is named The Weight of Air and Memory. Though dark with ink and sharp with detail, there is a spectral quality to Shah’s Gandhara prints, a sense of the uncanny breathed into this modernist container of the past in Chandigarh, city of the future. Nehru welcomed the new capital as “symbolic of the freedom of India”, but liberation was contingent on loss. The memory that weighs on this city is that of Lahore, the lost capital. Lahore, whose absence is the reason for Chandigarh’s presence. On Level 2, in the Government Museum in Sector 20, the room is quiet, but the air is heavy.