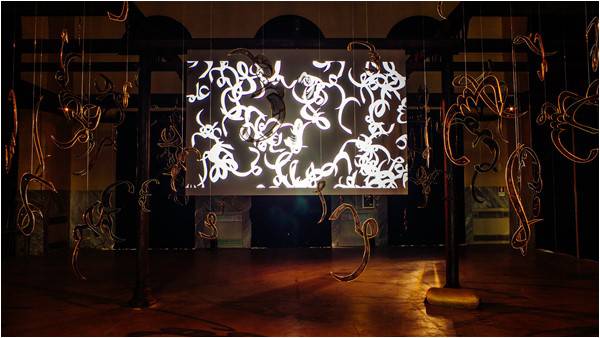

Entering Amin Gulgee’s latest exhibition in Rome, entitled ‘7.7’, housed at the Mattatoio di Roma (formerly known as Macro Testaccio), ostensibly provides the experiential antithesis to that of entering his simultaneous exhibition at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Roma Capitale (a review of which was published in The Friday Times earlier, titled That which we know not, on the 8th of June, 2018). You are at once struck by the dramatic intensity of ‘7.7’. The two adjoining rooms are darkened; the first, cathedral-like hall is occupied by a coal carpet, from which Gulgee’s calligraphic metal letters and the imposing Zero Gravity protrude, intermittently glinting, catching the artificial glare of the spotlights directed at the installation. The vectors of the coal carpet, in conjunction with the sound element – the mysterious notes of the rubab, a lute-like instrument that originates in Central Afghanistan – lead the viewer to the ethereal, suspended algorithmic projection, ensconced within a forest of coruscating wire letters. It seems almost dichotomous to the al fresco, sculptural ‘charbagh’ still on display at the Galleria d’ArteModerna, just twenty-five minutes away.

Yet such an impression is largely superficial. Despite the obvious aesthetic and spatial contrast, it is not a departure from ‘7’, but, in Gulgee’s own words, a “continuation”. This follows the conceptual logic of the whole series of exhibitions. Gulgee’s personal messages, encoded in his creative process and manifested in sculptural form, have a shared exegesis: the line in the fifth verse of the Surah al-Alaq, which states that God “taught man that which he knew not” (Quran, 96:5), deconstructed into seven parts. However, the form of the encrypted personal messages that Gulgee is transmitting through his art have undergone a process of transmutation over the course of the exhibitions, finally culminating in ‘7.7’. One could even go as far as to suggest that, with each iteration, Gulgee has developed a new and specific encryption with which to enshroud the content of his highly personal messages; an encryption of his reality. Thus, despite these metamorphoses, it is this conceptual nucleus that characterises ‘7.7’ as an amalgamation of the entire creative process of the ‘7’ series, encapsulating the artistic and curatorial emphases that have been pervasive throughout its four iterations.

Of the foremost aspects of Gulgee’s creative process throughout the production of the ‘7’ series, perhaps the most distinctive feature of his two Roman exhibitions has been the impeccable attention to site-specificity applied, not merely in the placement of works and lighting, but in the very conception of his installations. The space occupies an integral position in the inception of each installation, and through this, he is able to create a symbiotic relationship between the pre-existing architecture and lighting, and his artwork, unburdened by gratuitous spatial intervention. It is for this reason that, when we enter the La Pelanda section of the Mattatoio, we are greeted by an antithetical experiential effect to that of the installation at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna; the spatial context is utterly divergent, and as such, requires a divergent approach. To fully understand the versatility and nuance of Gulgee’s artistic interaction with the Mattatoio, it is important to first elucidate the spatial context of the venue itself.

Located in Rome’s former meat-packing district, the Mattatoio di Roma is a former slaughterhouse complex (‘mattatoio’ directly translates from Italian to ‘slaughterhouse’), re-purposed by the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma (Macro) as a dynamic contemporary art space. The section of the complex in which ‘7.7’ is situated, La Pelanda, is where animals were skinned (derived from the verb ‘pelare’ – ‘to skin’), and retains much of the pre-existing architecture from its rather brutal past, including, in the room adjacent to the exhibition, hooks from which carcasses were hung. In his sculptural installation, rather than avoiding the somewhat gruesome historical context of the space, Gulgee embraces it, hanging elusive wireletters from the pre-existing architecture, casting calligraphic shadows around the suspended projection that can be seen from both sides. In this aspect of the installation alone, we can clearly see two significant features of ‘7.7’, and the series of exhibitions more generally, co-existing and engaging in a mutually beneficial way. Gulgee has, by hanging both the letters and the plexi-glass screen (upon which the projection is cast), devised a means of not only interacting with the spatial context, but also establishing continuity with the previous iterations of ‘7’ through his projection of the same algorithmic piece that plays at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, also present in his show in Karachi, as well as the ethereal play of light created by the pendent characters.

This combination of innovation, versatility and continuity characterises ‘7.7’ as the amalgamation and culmination of the entire series of exhibitions, and Gulgee’s creative process more widely. This is conspicuous in the installation of the coal carpet, into which copper characters and Zero Gravity are embedded. Not only does this recall and connect the usage of a coal carpet in Gulgee’s Karachi exhibition – it transcends the self-referential and takes on a different form in ‘7.7’, not only providing a visual vector towards Zero Gravity and the ‘hanging’ room, but establishing a dark backdrop for the acute spotlighting to highlight the glinting mastery of metalwork and melding seamlessly into the overall darkness of the space.

Furthermore, Gulgee’s emphasis on the importance of performative pieces interacting with his sculptural installations has distinguished each manifestation of ‘7’, as well as his artistic output more generally. In a triumvirate of performative pieces, Gulgee encouraged the audience at the opening of ‘7.7’ to interact with his concept, without falling into the trap, ubiquitous in contemporary art, of didactic concept-explanation. During the opening, Sara Pagganwala spoke nonsensical Urdu (to a non-Urdu speaking) audience whilst inexplicably marking them with coal taken from the coal carpet; and Ana Rusiniuc silently marked herself with coal dust in almost choreographed repose, in and around the rectangular outcrop. These performances were perfectly complimented by an interactive performance entitled Love Letters, in which viewers of the exhibition write their own ‘love letters’ on a piece of paper, subsequently sealing them in glass bottles and placing them around the exhibition. Each of the performances imbued the audience with a tangible sense of both the creative process behind, and exegetic precept of ‘7’: Rusinuic’s performance embodied the highly-personal and meditative nature of Gulgee’s artistic process; Pagganwala’s performance gave the audience a tactile sense of the way in which Gulgee’s personal messages – his artwork – were interacting with each of them, in an incomprehensible yet overt manner; and Love Letters provided the audience with a cornerstone with which they could connect to the concept and process, by writing their own personal messages and sealing them, never to be seen or understood by anyone else, and installing them as part of the exhibition.

‘7.7’ challenges its audience to resist the temptation to see the exhibition as a departure from the previous iterations of ‘7’, encouraging the viewer to consider the installation in a more profound manner. Given such consideration, it becomes clear that ‘7.7’ is a continuation, an amalgamation, of the various aspects that have allowed audiences across the globe to engage with Amin Gulgee’s sculptural love letters.

‘7.7’ continues until the 26th of August. It is curated by Paolo de Grandis and Claudio Crescentini and co-curated by Carlotta Scarpa.

Yet such an impression is largely superficial. Despite the obvious aesthetic and spatial contrast, it is not a departure from ‘7’, but, in Gulgee’s own words, a “continuation”. This follows the conceptual logic of the whole series of exhibitions. Gulgee’s personal messages, encoded in his creative process and manifested in sculptural form, have a shared exegesis: the line in the fifth verse of the Surah al-Alaq, which states that God “taught man that which he knew not” (Quran, 96:5), deconstructed into seven parts. However, the form of the encrypted personal messages that Gulgee is transmitting through his art have undergone a process of transmutation over the course of the exhibitions, finally culminating in ‘7.7’. One could even go as far as to suggest that, with each iteration, Gulgee has developed a new and specific encryption with which to enshroud the content of his highly personal messages; an encryption of his reality. Thus, despite these metamorphoses, it is this conceptual nucleus that characterises ‘7.7’ as an amalgamation of the entire creative process of the ‘7’ series, encapsulating the artistic and curatorial emphases that have been pervasive throughout its four iterations.

Amin Gulgee's emphasis on the importance of performative pieces interacting with his sculptural installations has distinguished each manifestation of '7', as well as his artistic output more generally

Of the foremost aspects of Gulgee’s creative process throughout the production of the ‘7’ series, perhaps the most distinctive feature of his two Roman exhibitions has been the impeccable attention to site-specificity applied, not merely in the placement of works and lighting, but in the very conception of his installations. The space occupies an integral position in the inception of each installation, and through this, he is able to create a symbiotic relationship between the pre-existing architecture and lighting, and his artwork, unburdened by gratuitous spatial intervention. It is for this reason that, when we enter the La Pelanda section of the Mattatoio, we are greeted by an antithetical experiential effect to that of the installation at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna; the spatial context is utterly divergent, and as such, requires a divergent approach. To fully understand the versatility and nuance of Gulgee’s artistic interaction with the Mattatoio, it is important to first elucidate the spatial context of the venue itself.

Located in Rome’s former meat-packing district, the Mattatoio di Roma is a former slaughterhouse complex (‘mattatoio’ directly translates from Italian to ‘slaughterhouse’), re-purposed by the Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma (Macro) as a dynamic contemporary art space. The section of the complex in which ‘7.7’ is situated, La Pelanda, is where animals were skinned (derived from the verb ‘pelare’ – ‘to skin’), and retains much of the pre-existing architecture from its rather brutal past, including, in the room adjacent to the exhibition, hooks from which carcasses were hung. In his sculptural installation, rather than avoiding the somewhat gruesome historical context of the space, Gulgee embraces it, hanging elusive wireletters from the pre-existing architecture, casting calligraphic shadows around the suspended projection that can be seen from both sides. In this aspect of the installation alone, we can clearly see two significant features of ‘7.7’, and the series of exhibitions more generally, co-existing and engaging in a mutually beneficial way. Gulgee has, by hanging both the letters and the plexi-glass screen (upon which the projection is cast), devised a means of not only interacting with the spatial context, but also establishing continuity with the previous iterations of ‘7’ through his projection of the same algorithmic piece that plays at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, also present in his show in Karachi, as well as the ethereal play of light created by the pendent characters.

This combination of innovation, versatility and continuity characterises ‘7.7’ as the amalgamation and culmination of the entire series of exhibitions, and Gulgee’s creative process more widely. This is conspicuous in the installation of the coal carpet, into which copper characters and Zero Gravity are embedded. Not only does this recall and connect the usage of a coal carpet in Gulgee’s Karachi exhibition – it transcends the self-referential and takes on a different form in ‘7.7’, not only providing a visual vector towards Zero Gravity and the ‘hanging’ room, but establishing a dark backdrop for the acute spotlighting to highlight the glinting mastery of metalwork and melding seamlessly into the overall darkness of the space.

Furthermore, Gulgee’s emphasis on the importance of performative pieces interacting with his sculptural installations has distinguished each manifestation of ‘7’, as well as his artistic output more generally. In a triumvirate of performative pieces, Gulgee encouraged the audience at the opening of ‘7.7’ to interact with his concept, without falling into the trap, ubiquitous in contemporary art, of didactic concept-explanation. During the opening, Sara Pagganwala spoke nonsensical Urdu (to a non-Urdu speaking) audience whilst inexplicably marking them with coal taken from the coal carpet; and Ana Rusiniuc silently marked herself with coal dust in almost choreographed repose, in and around the rectangular outcrop. These performances were perfectly complimented by an interactive performance entitled Love Letters, in which viewers of the exhibition write their own ‘love letters’ on a piece of paper, subsequently sealing them in glass bottles and placing them around the exhibition. Each of the performances imbued the audience with a tangible sense of both the creative process behind, and exegetic precept of ‘7’: Rusinuic’s performance embodied the highly-personal and meditative nature of Gulgee’s artistic process; Pagganwala’s performance gave the audience a tactile sense of the way in which Gulgee’s personal messages – his artwork – were interacting with each of them, in an incomprehensible yet overt manner; and Love Letters provided the audience with a cornerstone with which they could connect to the concept and process, by writing their own personal messages and sealing them, never to be seen or understood by anyone else, and installing them as part of the exhibition.

‘7.7’ challenges its audience to resist the temptation to see the exhibition as a departure from the previous iterations of ‘7’, encouraging the viewer to consider the installation in a more profound manner. Given such consideration, it becomes clear that ‘7.7’ is a continuation, an amalgamation, of the various aspects that have allowed audiences across the globe to engage with Amin Gulgee’s sculptural love letters.

‘7.7’ continues until the 26th of August. It is curated by Paolo de Grandis and Claudio Crescentini and co-curated by Carlotta Scarpa.