What a year of globetrotting it’s been thus far, encompassing Southeast Asia, West Africa, the UK and the seat of former Ottoman power, Istanbul. And before that, my 6-week sojourn in Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore Feb-March, the highlights of which I’ve tried to capture in my ongoing travelogue published earlier. As an aunt remarked, I might be well on my way to becoming a modern female version of Ibn Battuta!

Like him, for me travel is never simply an exercise in the pleasures of tourism (though of course it is that too)—but rather, a way of getting immersed in the political and cultural zeitgeist of the moment that reveals the past in the present. Much learning occurs whilst exchanging views with scholars I meet as a result of the academic conferences I’m often attending in these locales. These travels also provide opportunities for solidarity-building around issues that have formed part of my activist scholarship over the decades.

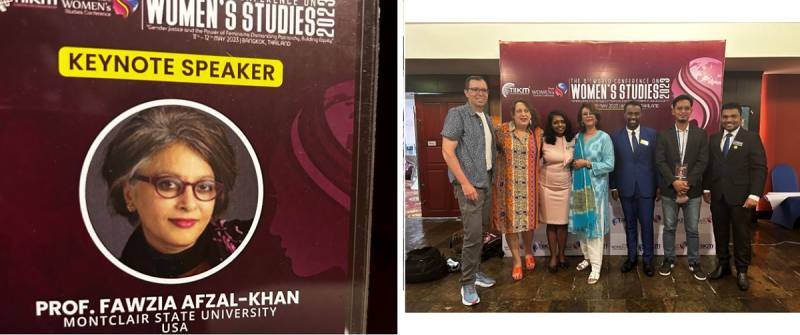

The first of my summer travels took me to Bangkok, where I’d visited my aunt and uncle (he was at the time working for UNICEF there)-40 years ago. Then I was just another graduate student working on my Phd in the USA; now, I returned as keynote speaker for a world conference on Women’s Studies, hosted by TIIKM—The International Institute of Knowledge Management, a conference platform based in Sri Lanka. My topic—the imbrication of capitalist-driven neoliberalism with illiberal and retrograde policies and outcomes for the majority of the world’s population comprised of women—resonated with other attendees and participants, coming as they did mostly from the global south which has suffered the results of a globalisation-from-above program that has hardly delivered the promised results of consumerist joy, lifting all boats.

But we were gathered there to think about resistance strategies, to register our globalisation-from-below paradigm, analysing data and exchanging stories from the West Indies, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Malaysia, China, to The Gambia, South Africa and beyond, around such globally interconnected issues as immigration, asylum, population growth, human trafficking, sustainable urban planning, education, in the process imagining better, fairer futures for all. Such a vision of progressive and equitable futurity is obviously one in which Europe and North America must be held accountable for the role they’ve played over centuries as colonisers and now imperialists who benefit most from the unjust, deeply gendered, economic systems they help keep in place around the globe, elevating national elites at the expense of the masses.

The social justice warrior colleague who invited me as the keynote speaker this year, is a Ashkenazi Jewish bisexual cisgender woman, who takes seriously her role in helping transform academic power structures so that the university can become a decolonial space. She is currently serving in the position of University Director of the Institute of Gender and Development Studies at the Regional Coordinating Office of the University of the West Indies, in Mona, Jamaica. Here, she is leading the effort to revise and update the university’s gender policy, to be more inclusive of alternative sexualities especially transgender communities.

Not only did the conference enable me to learn about the work she is doing working with local Indigenous Maroon communities to create sustainable development initiatives, but she, her friend from Rhode Island who is a lawyer working on human and refugee rights, and I, bonded over the challenges she described she and her progressive colleagues are facing at the Mona campus in their efforts to revise the gender policy to reflect contemporary developments in the area of gender and sexuality. Indeed, while returning to Bangkok after three heavenly days spent in a post-conference treat at the beach resort of Koh Samed, snorkelling and swimming in warm sea of what used to be called the Gulf of Siam—the three of us put our heads together devising and suggesting strategies to our friend, that could help move the progressive revisions along.

Interestingly, the arguments being made by opposing factions in the West Indian location, soaked as it is in the colonial religious ideology of a fundamentalist Christianity, are virtually identical to those being touted by the right-wing Islamic parties against the transgender rights movement in Pakistan; that such non-normative behaviours and identities are “western imports” which are meant to “destroy” local traditions and moral values. We noted the colonial irony inherent in such views, and I’ve since shared the revised policy document she and her team have co-written, with some of the leaders of the Trans movement in Pakistan.

This is just one instance of at least trying to build transnational solidarities, learning from each other’s experiences.

Meanwhile, against the backdrop of an authoritarian state system, where the elections then underway were seen as a referendum on whether it is illegal to criticise the Thai monarchy (the lese majeste laws)—the results of which continue to plunge the country into a political crisis—I was curious about the Kathoey (more popularly/derogatorily known as Ladyboy) subculture.

While cabaret shows featuring transgender performers are legendary—and I did enjoy attending one—the fact of the matter is that even though performance careers are open to this population, most other professions are not. Importantly, because there is no gender recognition law in place, trans citizens have to carry documents with a gender different from their identity and expression; they can and often are, humiliated by government employees when asked to provide documentation of gender identity.

The trifecta of sexism, classism and Islamism all woven together as a result of the economic fallout of Erdogan’s neoliberal policies, was on full display when I stopped over in Istanbul for 24 hours on my way home to New York from Bangkok. Here too, a follow-up election was underway to decide whether the Islamist Erdogan would return or be ousted after 20 years in power as strongman of Turkey by his secular opponent, Kilicdaroglu.

The desperation of the working classes against rampant inflation was manifest in young men roaming the streets and cafes for gigolo opportunities with foreign older women who look like they have money and are there for a good time (I was no exception for such attention); young cabbies decried the economic policies of Erdogan, saying they were drowning in debt; whereas older, more well-off businessmen such as the owner of a very large rug and carpet showroom I chanced upon, who spoke conversational English and invited me to sit and enjoy the ubiquitous Turkish coffee on a stool outside his shop, watching pedestrians go by, the dome of the Blue Mosque visible on the horizon—expressed nothing but contempt for naysayers against Erdogan.

For him, this was a true leader—who didn’t take orders from the West, who had brought national pride back in the glorious Islamic past of the Ottoman era, encouraging women to dress “decently” in accordance with Muslim mores, and as for accusations of an economic downturn, he asked me: “have you seen anyone begging in the streets here? Bah! Its all Israeli and US propaganda!”

After a few weeks of rest and recuperation, punctuated by workaholic frenzy putting together my presentation for a conference at Oxford—the first ever of its kind on Christians and Christianity in Pakistan—I took off for the UK.

The five days I spent there were blissful and exciting—the irony of locating such joy in the heart of Empire not being lost on me. But here we were, an assorted group of academics working in a variety of disciplines, gathered together to think through the injustices wrought in the name of a majoritarian state ideology against a religious minority. That minority had its roots too in a colonial system, one which exported Christianity as a tool to “civilise” the natives.

I was fascinated to hear about the creation of the widely misunderstood Anglo-Indian “caste”/class, another historical fallout of the British colonial era. It was great fun to hang out post-conference, with this young erudite scholar of Anglo-India, along with one of the conference organisers and his friend, singing Phantom of the Opera as we punted down the Cherwell on the only evening it rained in Oxford.

I am thrilled I got to meet Christian scholars and activists from Pakistan working hard to envision progressive solidarities that might turn Pakistan around, who received well my intervention on Christian popular culture; such cultural contributions I argued, nay, the enduring presence of Christians in Pakistan, helps us to queer the national imaginary-an urgent decolonial task. I am looking forward to working on collaborative projects with my Pakistani Christian brethren to further this activist scholarly agenda in service of a progressive Pakistani future.

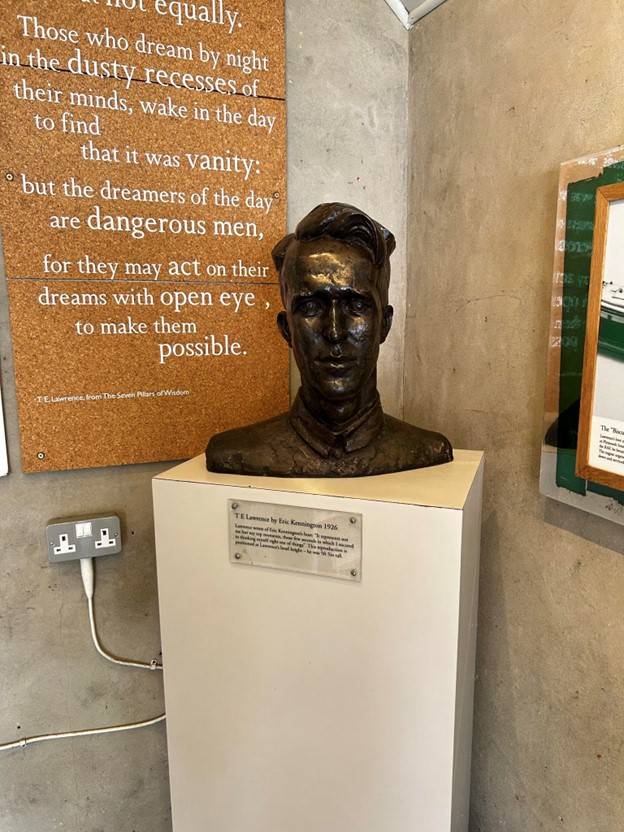

And of course I must mention my own postcolonial obsession with the figure of TE Lawrence, who attended Jesus college at Oxford after growing up in the town, and about whose spy activities in South Asia I’ve recently completed the first draft of a play co-written with Pakistan’s leading playwright, Shahid Nadeem of Ajoka.

Learning of his last residence, a labourer’s cottage he refurbished to suit his spartan tastes (but with a state of the art bathtub and plumbing!)—near Bovington Camp in Dorset, I prevailed upon my dear friends Robert and Badral Young, with whom I stayed for a few days post-conference in their lovely home in town—to drive me out there. Robert, a well-known scholar in postcolonial studies, understood my obsession, and kindly drove the three of us out there for a truly memorable summer outing.

The visit to Lawrence’s house, Clouds Hill, provided a fascinating window into the mind and habits of an extraordinary intellect, exemplifying in one person, the push-pull of colonialist fantasies inspiring the deeds of adventure, that led to Empire. Being in Oxford itself is like being in the belly of the beast, from which there seems to be no escape. The Great Game continues, and we are but players that strut and fret upon its stage, signifying nothing.

And yet, that isn’t quite right is it? Landing in Accra, Ghana, a few weeks ago at my final conference for the academic year, the annual International Federation of Theatre Research, where I am a long-term member of the Feminist Working Group, I was reminded of a history of Third Worldist struggle of which I, like many of my generation, are still participants in, no matter the unfashionability of the concept, or its pronounced failure. We continue to strut and fret in hopes of activating better futures.

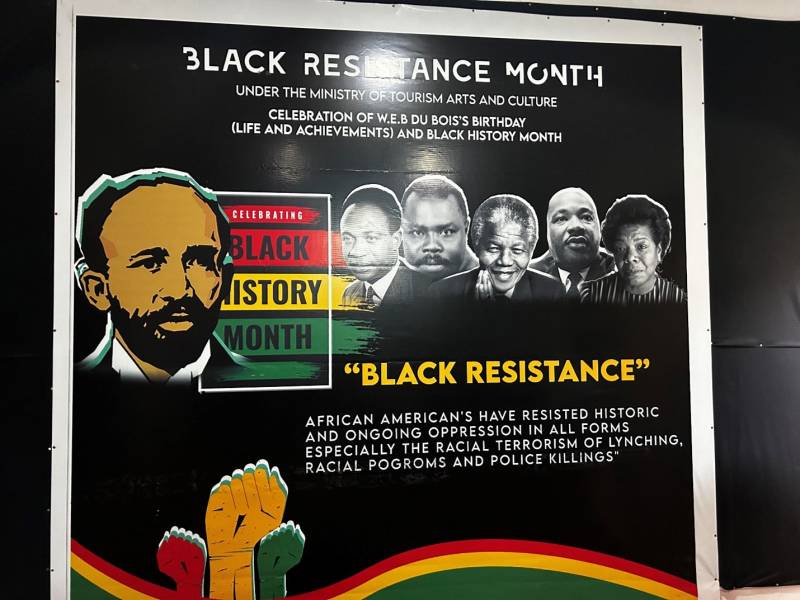

On the flight over, I (re) read WEB Dubois’ 1903 book of essays on race (and racism) in America, The Souls of Black Folk. I was struck by the contemporary resonance of so much he outlines, including his spot-on analysis of the roots of racism: capitalism, or in more contemporary parlance, what we would refer to as racial capitalism. His critique of Booker T. Washington fits the model of autocritique that remains so necessary in a third wordlist project today, to help move the “darker” nations beyond the neocolonial stage they are mired in post national independence, due to the sell-out politics embraced and followed by westernised ruling elites.

Indeed, such is the argument laid out in historical detail by Vijay Prashad in his 2007 book, The Darker Nations, where he describes how the progressive, promising Third world Project “came with a built-in flaw.” That flaw manifested itself in the alliance of worker and peasant classes in formerly colonised nations, with the landlords and emerging industrial classes to create a common/united front in the fight for independence.

Unfortunately, the people’s belief that the new independent nation state would promote a socialist program turned out to be an illusion, because once in power, “rather than provide the means to create an entirely new society, these regimes protected the elites among the old social classes” (xvii).

Today, we see the after effects of the faith placed in these neoliberal regimes, which tout individual empowerment as worthy goals, measurable in GDP increases tied to growth economies. These are themselves beholden in debt to the lending conglomerates of the New World Order such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which force structural adjustment programs down the throats of debtor countries as conditions of loan payments; these SAPS as we know, in the name of market reforms, pull the rug out from under the feet of the poor in these countries, gutting any notion of a welfare state that cares for, rather than crushes, its citizens.

Booker T. was wrong, in Dubois’ opinion, for promoting to Black folks an ideology of collusion with white supremacists as a way to partake in the crumbs of a profit-driven racial capitalism.

No wonder he made common cause with visionaries and revolutionaries like Kwame Nkrumah, who led Ghana-formerly known as the Gold Coast- to winning its freedom from British colonial rule in 1957—the first country on the African continent to do so. And I was thrilled to visit the house given by Nkrumah to Dubois, when the latter, at the age of 93, landed in Accra in 1961 at the invitation of the former; the two had become very attached to each other following their first meeting at the fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester in 1945, where three future African presidents were in attendance: Hastings Banda of Malawi, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana.

Dubois’s commitment to helping African nations achieve their freedom and build pan-African solidarity, endeared him to these leaders, and Nkrumah invited him to move to Ghana and help edit a new encyclopaedia on the African diaspora. He was given Ghanaian citizenship and while happily living and working in Accra, he passed away at the age of 95 in 1963.

It was quite moving to see posters and photos of him and his wife Shirley, a progressive activist, playwright, music composer and scholar and member of the American communist Party who spent several years in China and Egypt, meeting and greeting revolutionary figures like Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Maya Angelou as well as Mao Zedong, displayed alongside two large Chinese wall decorations gifted to them, and of course, the modest sized library containing an eclectic array of books, as well as graduation robes of colleges he attended including Fisk and Harvard universities. He and his wife are both buried in a tomb on the grounds of the house, and the ceiling is decorated in a motif that recalls a spider’s web: W.E.B.

It was this sense of a web of connections that pulled me in to the sights, smells, music and history of Ghana as discoverable in a short one week visit. When walking around Nkrumah Memorial Park, for instance, I found myself nodding in agreement with a statement attributed to Nkrumah painted on a wall: “I’m not African because I was born in Africa, but because Africa was born in me.”

I was transported back to my childhood and early adolescence, spent running on the beaches of Bathurst, Gambia, learning how to swim in the sea there, playing with my friends on the groundnut fields that surrounded our compound; then from there to Kampala, Uganda, attending Nakasero and Demonstration Secondary Schools, glimpsing Lake Victoria on clear days from the lawns of my parents’ home nesting in the hills of Bugolobi, discovering the pleasures of Bollywood cinema at the local drive-in, and the purple passion fruit with its bright orange flesh---fragrant, delicious Africa!

My feminist spirit was delighted to see and dance to an all-woman band cheekily named The Lipstick Queens, playing into the wee hours of the morning at a local club, the 233 Jazz Bar and Grill; and to meet, through our feminist research group, two young Ghanaian women who were bold and beautiful, challenging heteronormative patriarchal norms of their culture fearlessly through their gender activism around bodily rights among other struggles; it was a treat to see and hear them as they led a community workshop/speakeasy that introduced the feminist pan-African activist writings of the late Ama Ata Aidoo, who challenged neocolonialism alongside sexism and internalised racism and colourism within the Ghanaian society.

Watching students at University of Ghana perform a play written by a local playwright who has given Greek tragedy an Afrocentric twist, was wonderful, as we sat in the university amphitheatre treated to a production that made full use indigenous music, dance and storytelling traditions. Cultural decolonialism in action!

A day trip out of Accra was organised for conference attendees, where after a 4-hour bus ride --during which we fed ourselves on fried plantains and warm bread rolls being plied during traffic jams by a bevy of straight-backed local women carrying the supplies in tall mounds on their heads--we braved a hike on swaying rope bridges across a rainforest canopy; it was quite an adventure!

And then we drove to the coast, another couple of hours, until, rounding a hill, we came upon a white-washed castle sitting strategically on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. The irony of such a vision could hardly be lost on anyone: this was the perfect emblem of white power, conducting its dastardly deeds of kidnapping native Africans, raping and torturing them in the castle dungeons, putting those who survived such brutish treatment onto ships bound for the New World; there, to endure 400 years of slavery in servitude to the White Man, his Wife, their Children: the blackguards of history.

The labour of those Africans, torn from their lands and families, their communal culture and traditions of respect for the earth and water, that enforced labour is what fueled the engine of a rapacious capitalism that today has led the world to the edge of self-destruction.

A few days ago, not long after our return from Accra, my husband and I made a rather long road trip to Toronto, to visit childhood friends of his he hasn’t seen much of in the decades that have passed since. It was a conscious effort to make room for a love that we too often push aside in pursuit of other goals in our work-fueled frenzy encouraged by this profit-driven system we all participate in. After a most wonderful and yes-loving-reunion, we stopped by to observe the glory of Niagara Falls. Here, surrounded by natural beauty packaged into a consumerish hell of all kinds of merchandise, fast food, ticket fees etc—signboards acknowledging these lands and their waterways as belonging to Indigenous tribes who respected Mother Nature-- felt terribly hypocritical. But I want to read them in the spirit of the love we can and must rediscover in the course of our flawed human journeys.

This is the love that, according to one legend, led the Thunder Beings, a group of native Spiritual elders whose role was to protect life, to save a young woman referred to as the Maid of the Mist, from certain death when, depressed, she paddled her canoe over the Niagara Falls but instead of crashing over the cataract, landed safely at the bottom. The lesson here that is imparted to visitors is that just as these ancestral beings fulfilled their obligation to protect life by saving and then nursing the Maid of the Mist back to a fulfilling and happy life in times past, so too, in our present time, these spirit beings continue to nurture life through harnessing the kinetic energy of the Falls to provide power for families across Canada and North America.

Revealing the past in the present, saving our present through understanding our connection to our past. If we can join together our critical and creative abilities, create pathways of acknowledgment, of repentance and forgiveness, in the spirit of collaboration that defined the Non-Aligned Movement following the Bandung conference of 1955 which was meant to free us all from the shackles of colonialism and imperialism—well then, maybe there’s hope for our shared world. Let’s imagine, and bring into being, a world not just beyond borders, but one that can stitch together the fraying edges of an ecologically devastated humanity. Let us refuse, together, brown, black, and white, the ongoing colonisation of our lands, minds, and bodies.