The spectre of Marx and Lenin has resurfaced under the rubric of the Bangladesh crisis. From normal Bangladeshis, enthusiastic opinion makers and army of armchair critics unequivocally referring to the fall of Hasina’s fifteen years long authoritarian rule as Marx used to refer to the tragedy of history, followed by farce. Quoting Lenin’s famous words that ‘decades where nothing happens, and some weeks when decades happen’ is cheering on past events. The events were dramatic but not unimaginable as one hears the suppressed voices of students who were just asking the Hasina regime to behave democratically. They have been knocking at the parochial mindset of Hasina’s unforgivable rule.

The fact is that the power vacuum would be impossible for Nobel Prize winner Mohammad Younus to fill. He will be seen as a new messiah who will end the misery caused by Hasina’s undemocratic government even as the quota rule that used to be unjustifiably favor the few chosen against the majority of common Bangladeshis has been permanently suspended. The Bangladesh Supreme Court has already done its part, but the mischief of political nonsense at the behest of Hasina’s government didn’t comprehend that the new generation of Bangladeshis are not the children of Sheikh Mujib’s Bangladesh; they have no connection with the becoming of Bangladesh, irrespective of history books reminding them.

Bangladesh was not a post-colonial state, but a break away nation, from another break away nation - Pakistan. The chokehold of colonialism and its physical infrastructure ended in South Asia temporally in 1947, when India became independent from the yoke of British colonialism, and Pakistan became the first breakaway nation. The common understanding of a post-colonial state is the end of temporal features of colonialism - the direct rule. Second, the responses and experiences of interactions between the colonial power and the colonized people. In both manners, the seat of colonial imperialist tendencies remains intact through institutions. India is still colonized in that sense because its entire institutional mechanism from the bureaucracy to judiciary is still ‘very British’. Both break-away nations, Pakistan and Bangladesh carried that institutional imperialism.

Elections, including free and fair elections, are not a guarantee of success for post-colonial nations. The irony is that most electoral democracies are equally intolerant and favor majoritarian tyranny.

Another great irony has been that post-colonial nation-states didn’t know how to carve a new political identity without having a non-European sociohistorical experience with modernity. The critique of European modernity didn’t get any alternate responses, to form a different political identity based on indigenous territorial, historical, and ethnoreligious formations. The institutionalization of political identity was reduced to elections in all post-colonial states and break-away nations.

Elections, including free and fair elections, are not a guarantee of success for post-colonial nations. The second irony is that most electoral democracies are equally intolerant and favor majoritarian tyranny. For breakaway nations, that too becomes worse than that if there are no free and fair elections.

In Pakistan, the Army has a state and until it is the ruler of the fate of normal Pakistanis, no popular leader or messiah like Imran Khan could make any difference. The Army and its structure remain both the depositor and executioner of the colonial enterprise. Bangladesh can’t be different, therefore one needs to pause and reflect on what exactly happens after the effect of Hasina’s exit.

The Case of Bangladesh

All regimes including those run by authoritarians require two kinds of legitimacy - internal and external. The misrule of Hasina’s regime was written on the walls. There was no opposition, no inclusive characters of the regime. From the bureaucracy to the judiciary, all institutions were either co-opted or hijacked and opposition leaders were ousted from any participation. Public rage was simmering and perhaps echoes the sentiments of the common people who didn’t stop with the fall of Hasina’s rule. She never enjoyed internal legitimacy and carried her regime with the support of colonial institutional structures. As a breakaway nation, Bangladesh never had a settled democracy. The brutal killing of its founding father Sheikh Mujib, father of Sheikh Hasina and his entire family, was done at the behest of its army. Breakaway nations experience such events episodically because they don't have the ideological foundations of a new nation based on their own sociohistorical experiences.

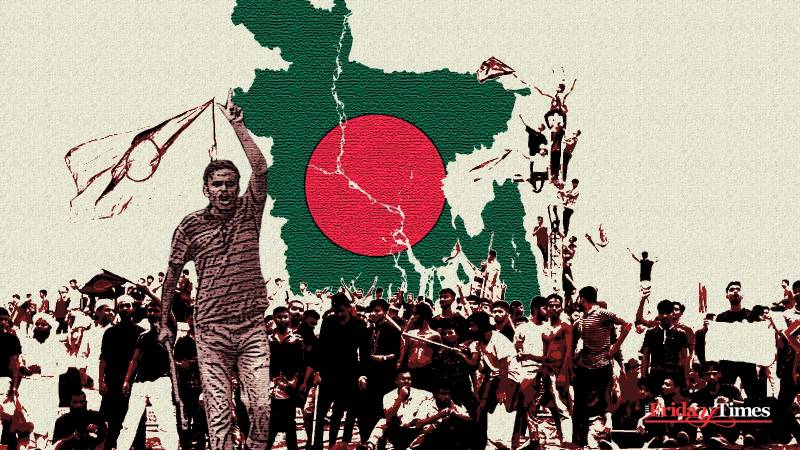

The act of revenge in the guise of revolutionist acts in streets of Bangladesh post Hasina’s exit including the defacing of Bangbandhu Mujib’s statues carries some significance. It is an act of claiming a separate political identity, distinct from Mujib’s Bangladesh. The violence one sees across Bangladesh, including the burning of textile factories and the killing of supporters of the Awami League goes however much deeper than carving a new political reality.

The power structure in Bangladesh’s history was always contested and poised against the possibility of a functional democracy. The Army will remain powerful and no new government can act independently until the separation between political institutions and security agencies is discrete.

The revolutionaries have turned to anarchy because there is no alternative in place. The BNP or Jamaat might be rejoicing over the outcome in their own interests, but they too will soon face a similar outcome, because there is no alternative for breakaway nations until the idea of a new nation and a new political identity is settled, after removing imperialistic institutions.

The power structure in Bangladesh’s history was always contested and poised against the possibility of a functional democracy. The Army will remain powerful and no new government can act independently until the separation between political institutions and security agencies is discrete, and they find a common understanding on what democracy means, and how to manage its inclusiveness and legitimacy from within.

If one looks at India, its democracy is functioning, with free and fair elections. India might have an independent judiciary, local governance and participation from the opposition, but it still lacks inclusivity and tolerance. It is still a nation in the making.

For India, despite many challenges since independence, its heterogeneity, territorial vastness, secular legacy and separate ethnonationalism does not lend any support to possible military takeovers, despite its colonial institutional structures remaining powerful. But for Pakistan and Bangladesh, these advantages are a non-factor.

The revolution on the streets forced the fall of Hasina, but it won’t be possible to create a democratic Bangladesh until it remains a simple breakaway nation, with all of its contradictions in place. Anarchy is a powerful force that the majority loves when there is a power vacuum.

Breakaway nations remain seated under the colonial guise through their own institutions. Even external legitimacy always remains subservient to a survival strategy. Bangladesh has been overly dependent on India, China and the US for external support to maintain the Awami League’s misrule. Another vital component missing for Bangladesh is a mismatch between the state’s politics and economics. Any upcoming political leadership will find it difficult to maintain its rule if there is misgovernance and the economic indicators could decide what could be the fall out of the mismatch.

One might argue that Bangladesh has excelled under Hasina’s rule, but economic indicators should also match political inclusiveness. The fact was she was ruling a dissatisfied majority through an iron fist. The lack of economic inclusivity, the deliberate suppression of political freedoms, intact colonial institutions, fragile external legitimacy and no legitimacy from bottom-up summed up the farce that Marx had referred to, that ultimately sealed the fate of Hasina’s rule.

For breakaway nations, there won’t be any relief until they create a bottom-up approach in balancing the top-down institutional framework for an independent and autonomous political identity. Perhaps that could be a possible approach to securing internal legitimacy and inclusive governance, not just elections or the nomination of Mohammad Younus. Dr. Younus might be the messiah that Bangladeshis want, but it would be impossible to create a democratic postcolonial nation-state if they understand that political identity is directly connected to political institutions.

The revolution on the streets forced the fall of Hasina, but it won’t be possible to create a democratic Bangladesh until it remains a simple breakaway nation, with all of its contradictions in place. Anarchy is a powerful force that the majority loves when there is a power vacuum. To establish a more durable political order could take years, despite the recent weeks having brought change that would otherwise have taken decades.