Pakistan is facing existential multi-dimensional crises of politics and economy with a highly dysfunctional state. It is about much more than democracy and debt. Short-term fixes and political engineering may not work this time. The country needs a radical break from the past policies but nobody wants to do it. Hence Pakistan could sink deeper into the quagmire especially if the IMF programme is not resumed within the next few weeks. There is no sign that the talks with the IMF are going to start soon as was previously indicated by the prime minister.

The government projected around $10 billion of pledges made at the Geneva Climate Conference of Pakistan’s donors as a great success but 90 percent of those are in the form of project loans to be utilised over a period of time and hence unlikely to help with the immediate balance of payments crisis. Further, there is a big question mark on whether the lending institutions would disburse the loans without the resumption of the IMF programme.

For the time being, Pakistan has managed to avoid default due to a $3 billion lifeline provided by the United Arab Emirates in the shape of a rollover of the $2 billion of existing debt and new financing of $1 billion. The Saudi Fund for Development (SFD) also agreed to fund $1bn worth of oil imports on deferred payment. The emergency assistance followed frenetic efforts by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and the army chief when they recently visited these gulf countries and pleaded for assistance as the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves fell to $4.3 billion – the lowest since February 2014 – during the first week of January.

Some believe Pakistan will muddle through the economic crisis because it is resilient, and has seen tougher times. This rear-view mindset is dangerous and based on flawed reasoning. I believe it will ultimately default, worse is yet to come. It is not like the past crises. Even during 1998-99, the track record of the current finance minister was nothing short of a disaster.

The IMF projects Pakistan’s total external debt to be around $138 billion by the end of the current fiscal year ending June 2023. Out of this, $103 billion is estimated to be public or government debt. Pakistan has to repay about $21 billion this year, and a total of $75 billion, or $25 billion per year, in the following three years to June 2026.

Pakistan’s current account deficit for the current fiscal year could be around $8 billion (compared to $17 billion in the previous year) primarily due to a sharp fall in imports. Pakistan’s goods imports fell by 22 percent (or by $9 billion) to $31 billion during the first half (July-December 2022) of the current fiscal year. However, the exports also fell by 5.8 percent to $14.2 billion.

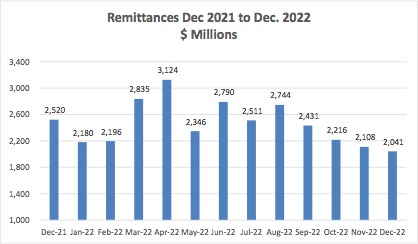

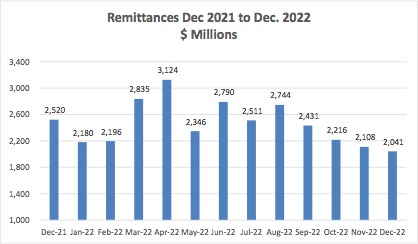

Remittances that averaged $2.6 billion a month during the FY 2021-22 have shown a declining trend, especially during the past three months (see the chart) since Ishaq Dar took over. The monthly average fell to $2.4 billion during the six months that ended in December 2022. At the current rate, total remittances could fall by $3 billion this year compared to the last fiscal year.

In addition to the remittances, there is another risk to Pakistan’s current account. Brent oil price that has traded $80-90 a barrel range since November 2022 could rise in 2023. Brent oil price’s highest weekly average in 2022 was $122 in June and the lowest was $76 in the first week of December 2022. Miftah Ismail managed a tough period when the oil prices were at their recent peaks but Pakistan’s external financial situation has worsened during the past three months despite falling international oil prices.

Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, believes that a barrel of Brent oil could reach $110 by the third quarter of 2023 if China and other Asian economies fully reopen from coronavirus restrictions.

Given the risks, it is indeed sad that the entire focus of the government has been on getting more loans and aid, and scant attention has been paid to reforms that could boost growth and exports, reduce unemployment and bring down inflation. Pakistan's elites know nothing more than to borrow.

Given that the debt servicing requirement would be around $25bn per annum for the next three years, Pakistan should seriously consider restructuring and rescheduling, instead of piling up more debt due to domestic political pressures.

Pakistan may be able to avert a default in the near term -- but make no mistake, it must and will have to radically change its protectionist trade and industrial policies to boost exports because that is the only sustainable way to reduce external debt and prevent the recurring balance of payments crises. The question is how?

Year 2022 was an abnormal year due to high oil prices. But in 2021 imports of intermediate inputs accounted for 53 percent of Pak imports, fuels for 24 percent and capital goods for 11 percent. Consumer goods accounted for only 7 percent of imports, while mobile phones for 4 percent. The issue is not just the imports.

The export market share of Pakistani firms has declined since 2000 – particularly over the last decade. In 2000, USD13 out of every USD10,000 worth of goods and services exported worldwide originated in Pakistan. This fell to only USD11 in 2020. In contrast, Vietnam increased its export market share from USD21 to USD127 over the same period.

The decline in Pakistan’s export market shares is generalised across sectors. Pakistan’s share in the global market for hides and skins, for example, shrank from 1.5 percent in the early 2000s to 0.8 percent in 2020. The share of Pakistan’s flagship export sector, textile and apparel, shrank from 2.3 percent to 1.8 percent over the same period.

The services sector also showed stagnation, with only modern services (that include exports of computer and professional services), has shown dynamism. Overall, Pakistan’s presence in global markets shrank since the turn of the century, while global trade almost tripled.

Actually, severe import restrictions hurt the industry as well as export-oriented industries. Pakistan's export per working person is less than half of Bangladesh's and less than 20 times of Vietnam. A World Bank study says Pakistan's export potential is USD 88bn but remains untapped due to high import duties, lack of market access, poor support services for entrepreneurs, and low productivity of Pakistani industrialists.

In short, given the rampant rent-seeking by big businesses under the umbrella of the ruling establishment, incentives and market environment are not favourable.

Pakistan’s merchandise export bundle (four-fifths of total exports) has not changed substantially for decades. Textile and apparel account for almost 60 percent, while the animal, vegetable, and foodstuff sectors combined account for 20 percent. Indeed, the number of product varieties exported by Pakistan fell over the decade, from an average of 3,167 in 2007–09, to an average of 2,894 in 2017–19. This implies that Pakistan fell in the world ranking of product varieties exported, from the 38th percentile to the 45th percentile.

Ishaq Dar's insistence on keeping the official exchange rate low compounded the problem. But it is not the only reason for Pakistan's dismal export growth. His bigger mistake was to increase import tariffs after 2013, which proved to be a major cause of stagnating exports, according to a study by economists at Oxford University.

According to Dr. Manzoor Ahmad, a trade economist, during the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) previous government, when import substitution policies were followed and customs duties were regularly increased – reflecting a tax share increase of almost 50 percent at the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) – Pakistan’s exports started falling. In terms of GDP, they decreased from 12.24 percent in 2013 to 8.58 percent in 2018, the lowest level since 1972.

Ministry of Commerce National Tariff Policy study (2019) stated: "The experience of developing countries demonstrates that the pace of development in those countries, which have undertaken programs of structural reform, tariff rationalization, and trade liberalization, was faster than the others. During the last decade, all the 20 fastest export growth economies have reduced import tariffs, while in Pakistan the trend has been the opposite with an increase of 11% in import tariffs. Additionally, the imposition of regulatory duties has increased the effective tariffs even higher. Currently, Pakistan maintains the highest average weighted tariff amongst the 70 countries having more than US$ 20 billion in annual exports.

Trade liberalisation helps boost trade overall (imports directly, but also exports by raising the relative rate of return of investing in the export sector). However, in the extreme case – where investors have no confidence -- trade liberalisation by itself is likely to boost imports without generating a significant export supply response. To maximise the growth boost, trade liberalisation must be part of a broader process of domestic reforms.

Elements of a business environment supportive of international integration are the 4 Cs: Confidence, [security, sound macro], Cost [labour and capital cost, regulations], Connectivity [openness, logistics] and Competence [education, skilled human resources]. Pakistan has specialised in low-skill, low-capability, low-value-added, and low-sophistication products.

Pakistan has turned more inward-oriented since the turn of the century. Increased inward orientation poses a problem because greater integration into the global marketplace is closely linked with faster productivity growth.

Moreover, 90 percent of Pakistan’s economy is driven by consumption with chronically low savings and investment levels. It must find ways to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) but FDI prospects are severely constrained by political instability, poor governance, including a highly flawed justice system, lack of skilled human resources, politically driven religious extremism in addition to the perception of Pakistan as a high-risk country due to geo-political conflicts and terrorism.

In short, although Pakistan desperately needs foreign investment, its political and economic policies have effectively discouraged and prevented foreign investment.

Some analysts believe the economic solutions are obvious: Pakistan needs political stability. This is a simplistic view and probably symptomatic and reflective of the inward orientation of many Pakistanis.

There is little recognition in Pakistan that as globalisation swept across the world after the fall of the Berlin Wall, countries like India, China, and Bangladesh seized the opportunities offered by trade liberalisation and progressed but Pakistan’s ruling elites continued to view the world through a cold war mindset and thought foreign aid would continue to enable Pakistan to extract geo-strategic rents.

Pakistan needs a 180-degree turn in its policies but its leaders and policymakers seem to be living in a fantasy land and gravely underestimate the challenges. Would they get their act together or would it take an event like a sovereign default to drive home the reality: there is no free lunch forever and in Pakistan’s case, those days might be numbered.

The government projected around $10 billion of pledges made at the Geneva Climate Conference of Pakistan’s donors as a great success but 90 percent of those are in the form of project loans to be utilised over a period of time and hence unlikely to help with the immediate balance of payments crisis. Further, there is a big question mark on whether the lending institutions would disburse the loans without the resumption of the IMF programme.

For the time being, Pakistan has managed to avoid default due to a $3 billion lifeline provided by the United Arab Emirates in the shape of a rollover of the $2 billion of existing debt and new financing of $1 billion. The Saudi Fund for Development (SFD) also agreed to fund $1bn worth of oil imports on deferred payment. The emergency assistance followed frenetic efforts by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and the army chief when they recently visited these gulf countries and pleaded for assistance as the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves fell to $4.3 billion – the lowest since February 2014 – during the first week of January.

Some believe Pakistan will muddle through the economic crisis because it is resilient, and has seen tougher times. This rear-view mindset is dangerous and based on flawed reasoning. I believe it will ultimately default, worse is yet to come. It is not like the past crises. Even during 1998-99, the track record of the current finance minister was nothing short of a disaster.

Brent oil price that has traded $80-90 a barrel range since November 2022 could rise in 2023. Brent oil price’s highest weekly average in 2022 was $122 in June and the lowest was $76 in the first week of December 2022. Miftah Ismail managed a tough period when the oil prices were at their recent peaks but Pakistan’s external financial situation has worsened during the past three months despite falling international oil prices.

The IMF projects Pakistan’s total external debt to be around $138 billion by the end of the current fiscal year ending June 2023. Out of this, $103 billion is estimated to be public or government debt. Pakistan has to repay about $21 billion this year, and a total of $75 billion, or $25 billion per year, in the following three years to June 2026.

Pakistan’s current account deficit for the current fiscal year could be around $8 billion (compared to $17 billion in the previous year) primarily due to a sharp fall in imports. Pakistan’s goods imports fell by 22 percent (or by $9 billion) to $31 billion during the first half (July-December 2022) of the current fiscal year. However, the exports also fell by 5.8 percent to $14.2 billion.

Remittances that averaged $2.6 billion a month during the FY 2021-22 have shown a declining trend, especially during the past three months (see the chart) since Ishaq Dar took over. The monthly average fell to $2.4 billion during the six months that ended in December 2022. At the current rate, total remittances could fall by $3 billion this year compared to the last fiscal year.

In addition to the remittances, there is another risk to Pakistan’s current account. Brent oil price that has traded $80-90 a barrel range since November 2022 could rise in 2023. Brent oil price’s highest weekly average in 2022 was $122 in June and the lowest was $76 in the first week of December 2022. Miftah Ismail managed a tough period when the oil prices were at their recent peaks but Pakistan’s external financial situation has worsened during the past three months despite falling international oil prices.

Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, believes that a barrel of Brent oil could reach $110 by the third quarter of 2023 if China and other Asian economies fully reopen from coronavirus restrictions.

Given the risks, it is indeed sad that the entire focus of the government has been on getting more loans and aid, and scant attention has been paid to reforms that could boost growth and exports, reduce unemployment and bring down inflation. Pakistan's elites know nothing more than to borrow.

Given that the debt servicing requirement would be around $25bn per annum for the next three years, Pakistan should seriously consider restructuring and rescheduling, instead of piling up more debt due to domestic political pressures.

Pakistan may be able to avert a default in the near term -- but make no mistake, it must and will have to radically change its protectionist trade and industrial policies to boost exports because that is the only sustainable way to reduce external debt and prevent the recurring balance of payments crises. The question is how?

Year 2022 was an abnormal year due to high oil prices. But in 2021 imports of intermediate inputs accounted for 53 percent of Pak imports, fuels for 24 percent and capital goods for 11 percent. Consumer goods accounted for only 7 percent of imports, while mobile phones for 4 percent. The issue is not just the imports.

The export market share of Pakistani firms has declined since 2000 – particularly over the last decade. In 2000, USD13 out of every USD10,000 worth of goods and services exported worldwide originated in Pakistan. This fell to only USD11 in 2020. In contrast, Vietnam increased its export market share from USD21 to USD127 over the same period.

The decline in Pakistan’s export market shares is generalised across sectors. Pakistan’s share in the global market for hides and skins, for example, shrank from 1.5 percent in the early 2000s to 0.8 percent in 2020. The share of Pakistan’s flagship export sector, textile and apparel, shrank from 2.3 percent to 1.8 percent over the same period.

The services sector also showed stagnation, with only modern services (that include exports of computer and professional services), has shown dynamism. Overall, Pakistan’s presence in global markets shrank since the turn of the century, while global trade almost tripled.

Actually, severe import restrictions hurt the industry as well as export-oriented industries. Pakistan's export per working person is less than half of Bangladesh's and less than 20 times of Vietnam. A World Bank study says Pakistan's export potential is USD 88bn but remains untapped due to high import duties, lack of market access, poor support services for entrepreneurs, and low productivity of Pakistani industrialists.

during the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) previous government, when import substitution policies were followed and customs duties were regularly increased – reflecting a tax share increase of almost 50 percent at the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) – Pakistan’s exports started falling. In terms of GDP, they decreased from 12.24 percent in 2013 to 8.58 percent in 2018, the lowest level since 1972, says Dr Manzoor Ahmad.

In short, given the rampant rent-seeking by big businesses under the umbrella of the ruling establishment, incentives and market environment are not favourable.

Pakistan’s merchandise export bundle (four-fifths of total exports) has not changed substantially for decades. Textile and apparel account for almost 60 percent, while the animal, vegetable, and foodstuff sectors combined account for 20 percent. Indeed, the number of product varieties exported by Pakistan fell over the decade, from an average of 3,167 in 2007–09, to an average of 2,894 in 2017–19. This implies that Pakistan fell in the world ranking of product varieties exported, from the 38th percentile to the 45th percentile.

Ishaq Dar's insistence on keeping the official exchange rate low compounded the problem. But it is not the only reason for Pakistan's dismal export growth. His bigger mistake was to increase import tariffs after 2013, which proved to be a major cause of stagnating exports, according to a study by economists at Oxford University.

According to Dr. Manzoor Ahmad, a trade economist, during the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) previous government, when import substitution policies were followed and customs duties were regularly increased – reflecting a tax share increase of almost 50 percent at the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) – Pakistan’s exports started falling. In terms of GDP, they decreased from 12.24 percent in 2013 to 8.58 percent in 2018, the lowest level since 1972.

Ministry of Commerce National Tariff Policy study (2019) stated: "The experience of developing countries demonstrates that the pace of development in those countries, which have undertaken programs of structural reform, tariff rationalization, and trade liberalization, was faster than the others. During the last decade, all the 20 fastest export growth economies have reduced import tariffs, while in Pakistan the trend has been the opposite with an increase of 11% in import tariffs. Additionally, the imposition of regulatory duties has increased the effective tariffs even higher. Currently, Pakistan maintains the highest average weighted tariff amongst the 70 countries having more than US$ 20 billion in annual exports.

Trade liberalisation helps boost trade overall (imports directly, but also exports by raising the relative rate of return of investing in the export sector). However, in the extreme case – where investors have no confidence -- trade liberalisation by itself is likely to boost imports without generating a significant export supply response. To maximise the growth boost, trade liberalisation must be part of a broader process of domestic reforms.

Elements of a business environment supportive of international integration are the 4 Cs: Confidence, [security, sound macro], Cost [labour and capital cost, regulations], Connectivity [openness, logistics] and Competence [education, skilled human resources]. Pakistan has specialised in low-skill, low-capability, low-value-added, and low-sophistication products.

Pakistan has turned more inward-oriented since the turn of the century. Increased inward orientation poses a problem because greater integration into the global marketplace is closely linked with faster productivity growth.

Moreover, 90 percent of Pakistan’s economy is driven by consumption with chronically low savings and investment levels. It must find ways to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) but FDI prospects are severely constrained by political instability, poor governance, including a highly flawed justice system, lack of skilled human resources, politically driven religious extremism in addition to the perception of Pakistan as a high-risk country due to geo-political conflicts and terrorism.

In short, although Pakistan desperately needs foreign investment, its political and economic policies have effectively discouraged and prevented foreign investment.

Some analysts believe the economic solutions are obvious: Pakistan needs political stability. This is a simplistic view and probably symptomatic and reflective of the inward orientation of many Pakistanis.

There is little recognition in Pakistan that as globalisation swept across the world after the fall of the Berlin Wall, countries like India, China, and Bangladesh seized the opportunities offered by trade liberalisation and progressed but Pakistan’s ruling elites continued to view the world through a cold war mindset and thought foreign aid would continue to enable Pakistan to extract geo-strategic rents.

Pakistan needs a 180-degree turn in its policies but its leaders and policymakers seem to be living in a fantasy land and gravely underestimate the challenges. Would they get their act together or would it take an event like a sovereign default to drive home the reality: there is no free lunch forever and in Pakistan’s case, those days might be numbered.