In the wake of the brutal massacre in North Waziristan last week, where six Saraiki labourers from Dera Ghazi Khan lost their lives, what adds to the distress is the apparent lack of attention and empathy from various segments of society towards the suffering of the Saraiki people.

In October 2023, ten labourers lost their lives in Turbat, Balochistan, in two separate incidents. The individuals targeted in the attack on the 14th of October hailed from my hometown in the Multan district. Regrettably, these incidents seldom garner national attention, and when they do, coverage is often confined to social media, only to be forgotten.

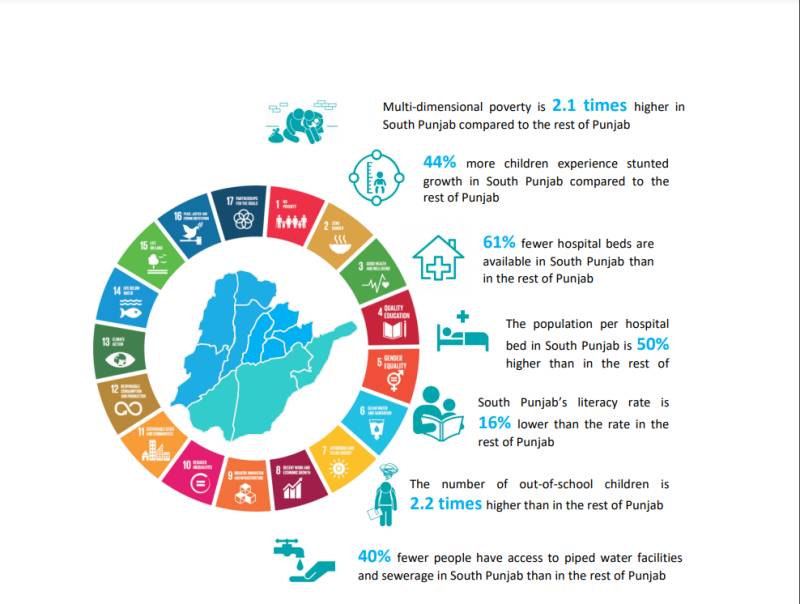

Rauf Klasra, a prominent voice from the Wasaib, aptly labelled ‘Pardes’ as a villain for Saraikis in his column. Over the last few decades, thousands of labourers and essential workers have migrated to the Middle East and remote areas of Pakistan. However, this migration has not led to noteworthy improvements in their lives or the lives of their loved ones. They continue to be victims of poverty, helplessness, and now brutal violence. A 2022 report published by the UN in Pakistan highlighted highly concerning development indicators in South Punjab, with multi-dimensional poverty twice as high as in the rest of Punjab.

As a Saraiki, it comes as no surprise to me that the unfortunate deaths of impoverished Saraiki labourers often result in framing a narrative such as "Terrorists killing Punjabis," a label employed by progressive writers like Muhammad Hanif and seasoned journalists like Hamid Mir. It is condemnable that they outrightly ignore the historical claims of the Saraiki intelligentsia and fail even to mention the struggle of the Saraiki people for a separate identity. Saraiki nationalists, scholars, and intellectuals have long highlighted the marginalisation of the Saraiki identity in the national discourse.

While we acknowledge that many journalists and columnists may have good intentions, it prompts a crucial inquiry into journalistic integrity and the responsibility associated with reporting.

This ongoing gaslighting only exacerbates the trauma, and if left unaddressed, it will pass on to future generations.

Twitter user Younas Jam has criticised the stance taken by prominent media figures, describing it as 'murdering the identities of the deceased Saraikis.' In his commentary, he addresses the structural oppression contributing to the denial of fundamental rights for the oppressed.

The question that @mohammedhanif raised at the end of this column is really interesting, “Students should ask Kakar which animal can he relate to from Animal Farm?”

— Younas Jam (@iYounasJam) January 8, 2024

This question should also be asked from the people who are constantly trying to murder 1/5https://t.co/uqjYgmEhoo

To clarify, those who were killed in Turbat and Waziristan were Saraikis belonging to underprivileged regions, seeking opportunities in remote areas to earn a dignified livelihood. They are not only victims of terrorism but also of poverty and systemic oppression. It is essential not to overlook this dual aspect of their plight.

The most concerning response has emerged not from mere internet trolls, as previously believed, but rather from an organised ethnic-supremacist and racist movement. They exploit the deaths of Saraiki labourers to advance their sinister agendas, fuelling hatred against Pashtuns and Balochs, particularly on social media platforms like Twitter.

He said "Seraikis back to the grave"

— The Donnie Darko (@TheDonnieDarko1) November 28, 2023

These are Punjabi ethnic supremacists racists pic.twitter.com/M3NT89lxJ0

It is disheartening when people downplay the gravity of racist posts that incite violence by dismissing them as only internet phenomena. It is crucial to highlight the rhetoric in mainstream electronic media and on critical public forums. In 2021, a retired army general insinuated that Southern labourers in the capital were mere beggars pretending to be workers.

Recently, at a PIDE conference, a participant echoed a similar sentiment, asserting that three out of four beggars come from the South. These ignorant and racist remarks not only elicit strong responses from Saraikis on social media but also from significant political bodies and student societies, such as the Saraiki Students Council at Quaid e Azam University in Islamabad.

To the left in Punjab, dear comrades a retarded General has given derogatory remarks against Saraiki laborers working in the twin cities.

— Amjad Mehdi (@amjadmehdi17) August 3, 2021

He attacked our symbol of resistance “☭”. Hope you’ll join us calling out this bigot publicly.

#سرائیکی_بھکاری_نہیں_تم_لٹیرے_ہو pic.twitter.com/aGyD88ITdt

i am literally part Saraiki would anyone of you losers have even known? what is wrong with Pakistan - what a rotted place saying we should be sent back to the grave?? for what!?!?!?!?

— Sabah Bano Malik (@sabahbanomalik) November 28, 2023

Mere days after Firdous Ashiq Awan spews racist bile against Sindhis we see an analyst claiming Seraikis are beggars.

— Nawab Hassan Hussein Qureshi (@HtotheQ) August 2, 2021

The racism against Pakistan's different ethnicities continues unabated but do not think we will take it lying down. We will call out your vile actions!

General (Rtd) Ejaz Awan's derogatory remarks against Seraiki people have caused a wave of anger. It represents colonial mindset of our Khaki elites who look down upon citizens from peripheries. Ejaz Awan must apologize for his racist comments.#سرائیکی_بھکاری_نہیں_تم_لٹیرے_ھو

— Ammar Ali Jan (@ammaralijan) August 4, 2021

Furthermore, there are two distinct reactions to the pleas of the Saraiki people. Firstly, there is a complete erasure of the Saraiki identity, as individuals, including not only racists and bigots but also prominent figures, display irresponsibility and ignorance by refusing to acknowledge the murdered labourers as Saraikis. This erasure extends to the appropriation of our language and culture.

Secondly, there is the issue of stereotyping and racism against Saraikis, with people unfairly labelling them as dacoits robbing Karachi, beggars ruining Pindi and Islamabad, and settlers occupying Punjab.

Saraikis are vigorously countering these hateful campaigns and making their voices heard, which is particularly significant in the current landscape of dissent politics.

Without delving into the intricacies of the debate surrounding the realisation of a separate province, it is crucial to emphasise that the Saraiki Wasaib is home to diverse ethnicities, cultures, and speakers of different languages.

Present-day Saraiki youth are actively engaged in self-education, participating in national discourse through a robust presence on social media, managing student societies at major educational institutions, and notably, contributing to pop culture, even utilising hip hop to express dissent.

In conclusion, the Saraiki movement is undeniably vibrant, offering new hope for a more prosperous future for the Wasaib.