The powerful play goes on… a show of glamour and folly, buttressing exclusionary notions of the past, with democratic undertones, and a tawdry production – the play in question being the 75-year long history of Pakistan, of course.

At the time of partition, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammed Ali Jinnah knew well that as a nascent nation, we had to ascribe to one primary identity before a native one – that of being a Pakistani. While this might come off as too rudimentary to be explicitly put out for a newly born nation, the Quaid knew exactly why it was necessary: for the previous 200 years the British had perched atop the Indian subcontinent not because of their military might or superior intellect but simply because they were able to exploit on ethnic lines and create divide within. Identifying as Pakistanis before anything else would, he believed, put this threat in the realm of mere remote possibility.

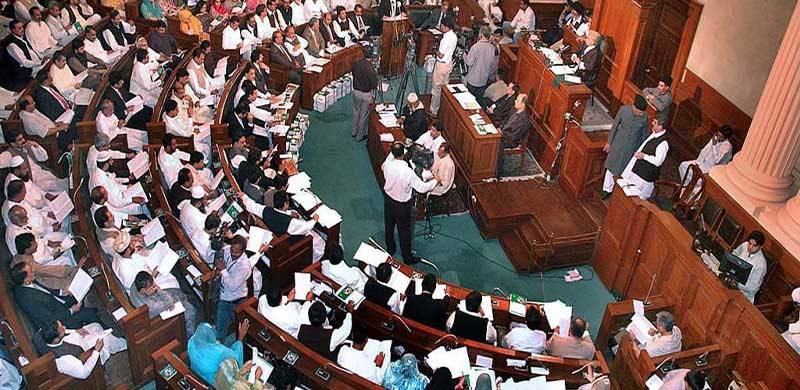

After all, we are a diverse nation, not just in populace and thought but also in system – from martial laws to democracy to federal state, it seems that we have tried it all.

But there’s been one constant for most of our history.

The gaudy corridors of power have always echoed in the plains of Punjab and resonated well with its people. Probably because it constitutes a majority, population wise, but that does not take away from its virulent effects.

One of many is the degeneration of the sense of belonging into the sense of deprivation felt by other parts of the country. Again, not the first time. Independence of Bangladesh in 1971 would be a fitting archetype. While it was the West as a whole depriving the East, the man of the hour, Yahya Khan happened to be a Punjabi.

It is not to say or allude to the idea that being a Punjabi is somehow criminal, but it definitely calls for a day of reckoning. Most nation states in the world have sub-states or provinces – some bigger than others – but with greater power comes greater responsibility. If misused, the chasm between provinces would only grow further. And this responsibility starts with acknowledgement of power and initiative that one harbours while also understanding and trying to help mitigate the problems of others without any thought for self-service.

Another constant has been the old-fangled fetishizing of the word ‘traitor’ whose initial reception in our history has been incendiary — arguably for the right reasons. Treason equates betrayal as it has been codified within our constitution. But particularly in Pakistan’s pretext, this betrayal has not necessarily been to the state but to instruments once intended for civilian service alone, under civil control: institutions like the military-oligarchal complex. Punjab’s ensuing silence leaves us with troubling notions, perhaps, it hardly contribute to accountability mechanisms for said institutions because they are at the other end of the bargain.

Besides, we know what happens to those who do – some never see their families or the sun ever again. Some sharpened critics might rightly point out that the so-called seditious rebels ‘betray’ because they have been aggrieved for the longest time. The Punjabis, on the other hand, see no grief. From wealth to power to infrastructure to monopolies – in every walk of life, from bureaucracy to industry – Punjabi’s unfettered access to privilege has rendered them blind, and now, they have become far too complacent to simply care.

Just a few days back, on an online discussion forum, someone went far enough to say that it would take Punjabis to suffer the same fate as those of other targeted communities to understand the intensity of their plight and to not leave it untouched.

It is ridiculous to know that such issues of national importance have gone almost wholly unrecognized in the mainstream media, not to mention the mystique that surrounds it. It is not even about one province or community nor is it about making a fatuous point. When the marginalized start to adopt a bellicose attitude, things are meant to get very real – even for those who are unaffected.

Be it missing persons in Balochistan or water distribution with Sindh or Baba Jan’s case, these issues cannot be cosseted in an enclosed box with a slothy attitude. The bottom line is that Punjab has to get more involved. It has to tout the old narrative of one nation and stand tall with everyone.

This is not some sort of starry-eyed romanticism, but Punjab has to give birth to traitors who defy the existing system and norms that exist within. The powerful play has to be re-written and Punjab “may contribute a verse”.

At the time of partition, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammed Ali Jinnah knew well that as a nascent nation, we had to ascribe to one primary identity before a native one – that of being a Pakistani. While this might come off as too rudimentary to be explicitly put out for a newly born nation, the Quaid knew exactly why it was necessary: for the previous 200 years the British had perched atop the Indian subcontinent not because of their military might or superior intellect but simply because they were able to exploit on ethnic lines and create divide within. Identifying as Pakistanis before anything else would, he believed, put this threat in the realm of mere remote possibility.

After all, we are a diverse nation, not just in populace and thought but also in system – from martial laws to democracy to federal state, it seems that we have tried it all.

But there’s been one constant for most of our history.

The gaudy corridors of power have always echoed in the plains of Punjab and resonated well with its people. Probably because it constitutes a majority, population wise, but that does not take away from its virulent effects.

One of many is the degeneration of the sense of belonging into the sense of deprivation felt by other parts of the country. Again, not the first time. Independence of Bangladesh in 1971 would be a fitting archetype. While it was the West as a whole depriving the East, the man of the hour, Yahya Khan happened to be a Punjabi.

The gaudy corridors of power have always echoed in the plains of Punjab and resonated well with its people. Probably because it constitutes a majority, population wise, but that does not take away from its virulent effects.

It is not to say or allude to the idea that being a Punjabi is somehow criminal, but it definitely calls for a day of reckoning. Most nation states in the world have sub-states or provinces – some bigger than others – but with greater power comes greater responsibility. If misused, the chasm between provinces would only grow further. And this responsibility starts with acknowledgement of power and initiative that one harbours while also understanding and trying to help mitigate the problems of others without any thought for self-service.

Another constant has been the old-fangled fetishizing of the word ‘traitor’ whose initial reception in our history has been incendiary — arguably for the right reasons. Treason equates betrayal as it has been codified within our constitution. But particularly in Pakistan’s pretext, this betrayal has not necessarily been to the state but to instruments once intended for civilian service alone, under civil control: institutions like the military-oligarchal complex. Punjab’s ensuing silence leaves us with troubling notions, perhaps, it hardly contribute to accountability mechanisms for said institutions because they are at the other end of the bargain.

Besides, we know what happens to those who do – some never see their families or the sun ever again. Some sharpened critics might rightly point out that the so-called seditious rebels ‘betray’ because they have been aggrieved for the longest time. The Punjabis, on the other hand, see no grief. From wealth to power to infrastructure to monopolies – in every walk of life, from bureaucracy to industry – Punjabi’s unfettered access to privilege has rendered them blind, and now, they have become far too complacent to simply care.

Some sharpened critics might rightly point out that the so-called seditious rebels ‘betray’ because they have been aggrieved for the longest time. The Punjabis, on the other hand, see no grief.

Just a few days back, on an online discussion forum, someone went far enough to say that it would take Punjabis to suffer the same fate as those of other targeted communities to understand the intensity of their plight and to not leave it untouched.

It is ridiculous to know that such issues of national importance have gone almost wholly unrecognized in the mainstream media, not to mention the mystique that surrounds it. It is not even about one province or community nor is it about making a fatuous point. When the marginalized start to adopt a bellicose attitude, things are meant to get very real – even for those who are unaffected.

Be it missing persons in Balochistan or water distribution with Sindh or Baba Jan’s case, these issues cannot be cosseted in an enclosed box with a slothy attitude. The bottom line is that Punjab has to get more involved. It has to tout the old narrative of one nation and stand tall with everyone.

This is not some sort of starry-eyed romanticism, but Punjab has to give birth to traitors who defy the existing system and norms that exist within. The powerful play has to be re-written and Punjab “may contribute a verse”.