It flowers in the 12th century and is in bloom also in the 19th. Thereafter, a new era emerges. But from Farid to Farid there are eight centuries of classical and exhilarating expression of the ardent pursuit of truth and a bold dissection of the phenomena of self, life and all the enigmas it offers, and yes, death. Eight luminous beads that reflect the same light but in varied shades, come to comprise what is generally recognised as the rosary denoting the lustrous tradition of classical Punjabi spiritual poetry. Eight different people, different minds, different temperaments, different voices, different milieus and different words. But a unity of conviction as well as of thought. Divergence in appearance and style but no difference really between the journeys and the destinations. Or between the underlying and connected anguish, passion, and ecstasy.

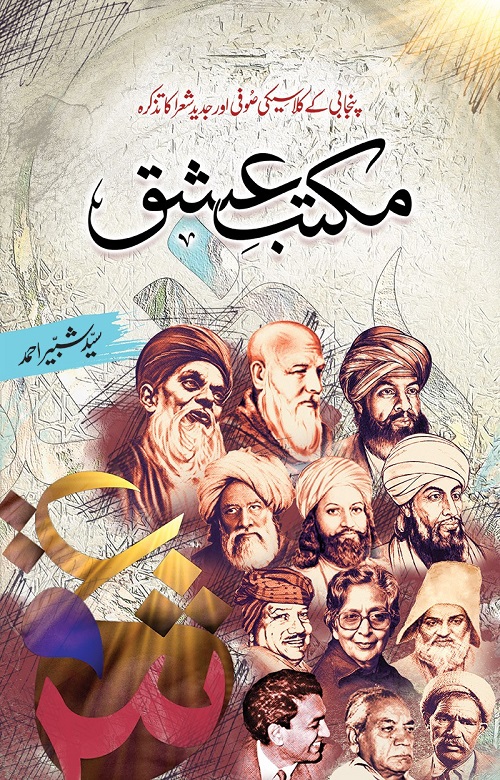

Syed Shabbir Ahmad’s lovingly compiled volume on Punjabi poets is a testimony to his lifelong devotion to the genre - a vitalising and refreshing pool from which he has obviously drunk often and deeply. It is a fantastic primer for anyone seeking an introduction to this glorious tradition

With Baba Farid Ganj Shakar it begins. The vital insight that the lamp of spiritual awakening must be lit within to disperse the darkness of a moonless night. So that change is not outwardly, but actual. He says:

باہر دِسّے چاننا، دل اندھیاری رات

Bahir dissay chanana, dil andhiari raat

Once one lights that flame of awakening, one soon discovers that one bends one’s will to someone else’s - not unlike a soaring kite flown by someone. As Shah Hussain puts it so beautifully:

ساجن دے ہتھ ڈور اساڈی میں ساجن دی گڈی

Saajan dai hath dor asadi mein saajan di guddi

With that awakening arrives also the recognition that the elixir that one seeks also lies within one. Thus, Sultan Bahu exhorts:

ناں کر منت خواج خضر دی تیرے اندر آب حیاتی ھو

Naan kar minnat Khwaj Khizar di tairay andar aab hayati hoo

What boundless bliss then it is to find true spiritual communion. A joyous Bulleh Shah hears a peacock calling in the forest of love:

ایس عشق دی جھنگی وچ مور بولیندا

Ais Ishq di jhungi vich mor bulenda

Lost in the wonders of love, the Sufic heart remains aware always of the transient and finite nature of earthly life. Waris Shah reflects that he hasn’t ever come across anyone who could entice back those who have left us.

ایہا کوئی نہ ملیا میں ڈھونڈ تھکی جیہڑا گیاں نوں موڑ لیائوندا ای

Aiha koi na milya mein dhoond thaki jaihra gayan nun mor liaonda ei

Inflamed and subsumed by true love Hashim Shah describes how this heathen thing which is a passionate temperament makes one perpetually wander in the streets.

ہاشم خاک رلاوے گلیاں، ایہہ کافر عشق مزاجی

Hashim khak rulaway galiyan, aih kafir ishq mazaji

But ultimately everything comes to an end. Mian Muhammad Bakhsh captures the pathos of this mortality when he says that neither the lamp flame lasts forever nor do the doting moths.

سدا نہ لاٹ چراغاں والی سدا نہ سوز پتنگاں

Sada na laat charaghan wali sada na soz patangan

So then why tarry and get attached to a place where the beloved is not visible, asks Khawaja Ghulam Fareed:

غلام فریدا اُوتھے کی وسنا جتھے یار نظر نہ آوے

Ghulam Fareeda uthay ki wasna jithay yaar nazar na avay

Syed Shabbir Ahmad’s lovingly compiled volume on Punjabi poets is a testimony to his lifelong devotion to the genre - a vitalising and refreshing pool from which he has obviously drunk often and deeply. It is a fantastic primer for anyone seeking an introduction to this glorious tradition as well as a great read for even those familiar with this remarkable body of poetic expression. It not only provides helpful brief biographies of the poets and an overview of their context and times, but a representative selection of their works with explanations as well as the author’s nuanced assessment of their places and distinctiveness in the Punjabi poetic tradition. In addition to engaging essays on the eight Sufi poets known as masters of Punjabi verse as well as great mystics and moral role models in the first section called “Sufi Rang”, we are offered essays on thirteen modern Punjabi poets of great vigor, variety, and individuality in the section called “Punjab Rang.” Whilst classical Sufi Punjabi poetry is part and parcel of our collective consciousness and lore, this modern poetry also resonates deeply at multiple levels with anyone who has experienced Punjab - who has loved it and felt the love it offers.

Syed Shabbir Ahmad’s lovingly compiled volume on Punjabi poets is a testimony to his lifelong devotion to the genre - a vitalising and refreshing pool from which he has obviously drunk often and deeply. It is a fantastic primer for anyone seeking an introduction to this glorious tradition as well as a great read for even those familiar with this remarkable body of poetic expression. It not only provides helpful brief biographies of the poets and an overview of their context and times, but a representative selection of their works with explanations as well as the author’s nuanced assessment of their places and distinctiveness in the Punjabi poetic tradition. In addition to engaging essays on the eight Sufi poets known as masters of Punjabi verse as well as great mystics and moral role models in the first section called “Sufi Rang”, we are offered essays on thirteen modern Punjabi poets of great vigor, variety, and individuality in the section called “Punjab Rang.” Whilst classical Sufi Punjabi poetry is part and parcel of our collective consciousness and lore, this modern poetry also resonates deeply at multiple levels with anyone who has experienced Punjab - who has loved it and felt the love it offers.

Why does it impact us so? I can only speak for myself. How does one describe the fragrance of the lilac Dharaik flowers as summer sets in? Or the distant echoing sound of the village mill that as a child I often confused with the persistent song of the Coppersmith Barbet. And as one strolled deeper into summer, the strident crow during unending afternoons. The frenzied Koel as monsoons swept in and drenched everything. The sound of someone singing the Heer traveling darkening crop fields as the day extinguished. For certain memories, sensations and emotions, I have always found the language indigenous to one’s ancestral land and organic to one’s early years to be far more evocative than others. Especially when it comes to verse. Invariably it creates mental images of flora, fauna, seasons, times of the day and indeed moments of hilarity and rapture as well as deep sadness that start sounding less evocative when translated. Less colourful. Less musical.

In Punjab Rang we come across a broad spectrum - philosophical speculation, revolutionary zeal, deep anguish and the thrill of love.

We find Qadir Yar amongst whose prominent works is his Qissa Puran Bhagat and who dwells on the nature of Divinity and the phenomenon of infinity:

رب بے پروا بے انت ہے جی اوہدا انت حساب نہ آئوندا ای

Rab bai parwa bai unt hai jee ohda ant hisaab na aonda ee

What particularly fascinates me is how time and again we have the great romantic lore of Punjab revisited, reinterpreted and reinvented. Here the working-class popular poet Jogi Jehlami laments Ranjha’s regret and helplessness as Heer is taken away by the Kheras:

ڈاہڈا ستایا عشق نے دردر پھرایا عشق نے

ٹِلے پہنچایا عشق نے جوگی بنایا عشق نے

پر ہیر سی جو دوستو اوہ سیدا کھیڑا لے گیا

میں ویکھدا ای رہ گیا میں ویکھدا ای رہ گیا

Dahda sataya ishq nai dar dar phiraya ishq nai

Tillay puhanchaya ishq nai jogi banaya ishq nai

Par Heer si jo dosto ooh Saida Khera lai gaya

Mein waikhda e reh gaya mein waikhda e reh gaya

However, in Professor Mohan Singh’s verse - one of the founders of modern Punjabi poetry - Heer is asked to let go the Kheras if she truly desires Ranjha:

میرا رانجھن موڑ دے

میرا رانجھن مینوں موڑ دے

جے ہیرے تینوں لوڑ رانجھن دی

لڑ کھیڑیاں دا چھوڑ دے

نالے رانجھن نالے رکھنی ایں کھیڑے

اے جھیڑے تیرے کون نبیڑے

Mera Ranjhan mor dai

Mera Ranjhan mainon mor dai

Jai Heeray tenon lor Ranjhan di

Lar Khairiyan da chord ai

Nalay Ranjhan nalay rakhni ain Kheray

Ai Jhairay teray kon nabairay

Whilst this appears to lay the blame on Heer, what a strong rejoinder by the popular poet Ahmad Rahi. Here Heer says to Ranjha that had he been more resolved and assertive like Mirza Jatt, they would have both fared far better. Empowered by his strength she would have taken on Kaidu and the Qazi, and both would have evaded their tragic deaths.

جے توں مرزا ہُندوں رانجھیا

تے میں تتڑی زہر نہ پھکدی

ساڈے پیار دی سانجھی پینگ نُوں

بھیڑی موت توڑ نہ سکدی

تری کڑی کمان دے مان تے

وے میں کیدو، قاضی ڈکدی

نہ توں بن آئیوں مردوں

نہ میں بن آئیوں مر دی

Jai tun Mirza hundon Rajhiya

Tai mein tatri zehar na phukdi

Saday pyar di sanjhi peeg nun

Bhairi maut tro na sakdi

Teri kari kuman dai man tai

Way mein Kaido, Qazi dakdi

Na tun ban ayon madon

No mein ban ayon mardi

In Syed Shabbir Ahmad’s lovely anthology, we also find the haunting poetry of the ascetic Daim Iqbal Daim who envisions the unending cycle of love and longing that transcends life and death. The eternal tales appear and reappear in new forms and the story continues and stretches on and on like the Thal desert. So appropriate given his themes is his nom de plume - Daim or eternal:

سک جان پانی دریاواں دے اگ عشق دی بل بل نئیں مکدی

سڑ سڑ پروانے نئیں مکدے ایہہ شمع وی جل جل نئیں مکدی

لیلاں دیاں کالیاں زلفیں تھیں مجنوں دیاں لمیاں راتاں نیں

راہ مکدے راہی مک جاندے، ایہہ منزل چل چل نہیں مکدی

سکھیو تسی جم جم سکھ وسو، دُکھیاں دی کہانی نہ چھیڑو

آہ دل دی دھڑکن سینے دی، نیناں دی ڈل ڈل نہیں مکدی

کدھی شمع نہ دائم بجھنی اے، اونہاں کیچ دیاں اسواراں دی

سسی دے ڈونگے پینڈے نیں، تھل نہیں مکدا گل نہیں مکدی

Suk jaan pani daryawan dai ag ishq di bal bal naeen mukdi

Sar sar parvanay naeen mukday aih shama vi jal jal naeen mukdi

Laila diyan kaliyan zulfan thain Majnoon diyan lamiyan raatan nain

Rah mukday rahi muk janday, aih manzil chal chal naeen mukdi

Sakhiyo tussi jam jam sukh wasso, dukhiyan di kahani na chairo

Aah dil di dharkan seenay di, nainan di dul dul naeen mukdi

Kadhi shama na daim bujhni ai, onhan Kaich diyan aswaran di

Sassi dai doongay painday nain, Thal naeen mukda gal naeeen mukdi

Featured also in the anthology is Lahore’s valiant son Ustad Daman whose soul was set on fire by the passion and defiance of that other great son of Lahore - Shah Hussain. Daman always stood up to autocrats with great verve and elan. Here he says he shall firmly stand by Fatima Jinnah against General Ayub Khan:

پتر نال مقابلہ ماں دا اے

پتر اسیں وی آں، اپنی ماں ول آں

سانوں صدر دے سائے دی لوڑ کوئی نہیں

اسیں ٹھنڈی بہشتاں دی چھاں ول آں

Puttar nal muqabala maan dai ai

Puttar asi vi aan, apni maan val aan

Sanon sadar dai sayay di lor koi nain

Aseen thandi bahishtan di chaan wal aan

Then we have the revolutionary poet Darshan Singh Awara, also from the rich soil of Jhelum, who assails false piety, empty ritual and self-indulgent clergies and their neglect of ordinary people:

جتھے گھر وچ گھپ انھیرا اے پر مندریں دیوے بلدے نیں

گھر بچے بھکھے مردے نیں خنگاہیں کتے پلدے نیں

Jithay ghar vich ghup anhaira aiy par mandar deeway balday nain

Ghar bachay bhukhay marday nain khangaheen kuttay palday nain

In addition, the volume contains essays on another major pioneer of modern Punjabi poetry Shareef Kunjahi; the revolutionary Naseer Kavi of Tilla Jogian; and three accomplished poets who defined Punjabi popular and film songs - the aforementioned Ahmad Rahi, Huzeen Qadri, and Bari Nizami. Indeed, this anthology is very valuable in informing us more about those who have made wonderful contributions but are relatively lesser known.

The only female voice in the anthology is the highly poignant and melancholic one of Amrita Pritam whose famous lament on Partition violence and call of anguish to Waris Shah haunts us to date. There is such moving wistfulness in her poetry. Here is a brief example:

میں تینوں فیر ملاں گی، کتھے، کس طرح، پتا نہیں

شاید تیرے تخیل دی چھنڑک بن کے

تیرے کینوس تے اتراں گی

Mein tainon fir milan gi, kithay, kis tarah, pata nahin

Shayad teray takhayul di chanrak ban kai

Teray canvass tai utraan gi

Any such anthology would be incomplete without Punjabi’s Keats, the charming Shiv Kumar Batalavi whose distinctive love poetry continues to impact readers on both sides of the border. I love the imagery of this poem which compares the colour of the newly dawned day to the lover’s complexion:

اج دِن چڑھیا تیرے رنگ ورگا

تیرے چُمن پچھلی سنگ ورگا

ہے کِرناں دے وچ نشا جیہا

کسے چھینبے سپّ دے ڈنگ ورگا

جے ضرباں دیواں وہیاں نوں

تاں لیکھا ودھدا جانا ہے

میرے تن دی کلی کرن لئی

تیرا سورج گہنے پینا ہے

تیرے چُلھے اگ نہ بلنی ہے

تیرے گھڑے نہ پانی رہنا ہے

ایہ دن تیرے اج رنگ ورگا

مُڑ دن دیویں مر جانا ہے

Aj din charhiya teray rang warga

Teray Chumman pichli sang warga

Hai kirnan vich nasha jaiha

Kisay chainbay sapp dai dang wargha

Jai zarban daiwan wahiyan nun

Taan laikha wadhda jaana hai

Meray tan di kali karan layi

Tera suraj gehnay paina hai

Teray chulhay ag na balni hai

Teray gharay na pani rehna hai

Aay din teray aj rang warga

Mur din diwain mar jana hai

Syed Shabbir Ahmad’s labour of love is a great service to a beautiful language and its millions of lovers. It has been characteristically published by Book Corner Jhelum with fine taste and attention to detail. One hopes that Shah sahib will continue to enrich our lives through more books on Punjab and Punjabi verse.