The dissenter, the critic, the rebel, the independent thinker, the human rights activist, the historian, the journalist, and even those who launch armed attacks against the state and citizens, all fall under the state’s radar as potential anti-state offenders. To identify an anti-state “element”, location is everything (historic and current). Distance from the political power centre, from the ethnic and religious majority, and access to actual weapons or dangerous ideologies serve as props for the state to manufacture the anti-state minotaur.

Anti-state anxiety attacks

Since the very birth of Pakistan was in the form of a monozygotic split of West and East, the state versus anti-state tension was perhaps predictable. But even after the political separation of physically and culturally unconnected lands, state-belonging in Pakistan continues to depend on linguistic, ethnic and religious differences. Only gender and class serve as more stable levers that determine state access and patronage.

Under ZA Bhutto’s rule, the distant Bengalis were easier to suspect as prone to sedition, while the intimacy of Ahmedis made it necessary to reinvent them as counterfeit citizens. In Zia ul Haq’s time, women, socialists and Sindhis were condemned as westoxified, godless anti-nationalists. The status of the Baloch, Pakhtuns and Mohajirs has depended on the political and economic contracts that they have brokered or broken with the rentier state.

A little dissonance maintains the image of a magnanimous state that gives its people ‘agency’ – to vote, pray, disagree within approved parameters, or collect some charity. But agency is not opposed to power, which is a commodity jealously guarded by our state that, in turn, is never neutral. To successfully claim rights or wrest a share of resources or powers that are monopolised by the state – either in the form of hard cash or simply, the license to use violence as a means of income or political power - you have to be a patron, benefactor, or proxy of this state.

Exceptionalism and escape

The law of state exceptionalism allows selective forgiveness - for Munawar Hasan but not Hussain Haqqani, for Junaid Jamshed but not Asia Bibi, for Zaid Hamid but not Zahid Hamid, for General Musharraf but not Nawaz Sharif, even for the Tehrik-i-Taliban and Noreen Leghari, the would-be ISIS recruit, but not for Alamzeb the PTM activist in jail, and so on.

The proximity argument holds more weight when we consider how the state has historically sponsored jihadist proxies. Some jihadist outfits and their madrassas are protected as patriotic defenders of the Islamic Republic while others are scheduled as anti-state. Their positions on the list of banned outfits fluctuates as much as the KSE these days. Although the anti-state actor is cast as spurious, hostile and dangerous, there is salvation if he is willing to be de-radicalised and rehabilitated into the fabric of national compliance.

The term ‘actor’ accurately defines how nationalism is a performance (think, Hamza Abbasi) and the ‘non-state actor’ is easier to identify due to his disruptive attacks on the state. But how do so many activists, reformers, intelligentsia and those ubiquitous ‘concerned citizens’ who are constantly pressurising the state to ‘do more’, relinquish rights and privatise itself, manage to escape the anti-state label?

All through the Musharraf regime, the entity that came to call itself ‘civil society’ (including the fourth estate, the media), and that is ostensibly a watchdog of the state, actively embraced and enabled this ‘liberal’ military dictator. For a decade, we witnessed sycophantic fashion designers tailoring the emperor’s robes, and servile organisers of film and culture festivals hosting ribbon-cutting ceremonies for the military usurper. We witnessed fawning film-makers document their dinners with a dictator and opportunistic activists participate in policy-making and elections that fortified a military regime. Pliant bureaucrats would jump with excitement if the uniformed ‘CEO’ turned up to a civic event, and Janus-faced journalists extended the coup-maker their sympathy as the country protested on the streets. Always ready to fiddle with Nero, a facile bourgeoisie swayed along to the political melody played for the adventurist architect of Kargil at countless balls and Qawali mehfils.

Slings, arrows and slogans

If the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and the women’s movement were the courageous forces of resistance against General Zia’s brutal regime, then the only challenge to General Musharraf’s praetorian rule was from the Lawyers Movement. However, the legacies of these battles have been mixed. The women’s movement of the 1990s fragmented into NGO-led projects and lost its radical edge, and the Lawyers Movement is often undermined retrospectively, as one co-opted by the intelligence agencies.

The point here is not about the compromises of resistance movements but to assess the options they faced after their rise against the state. Today, the PTM is the only force of defiance against this Sisi-like, military-led civilian rule. When the state changes its game, so must the politics of resistance.

Under ZA Bhutto, the materialist slogan ‘Roti, Kapra Aur Makaan’ resonated with a global wave of welfare socialism. Under Zia ul Haq’s dictatorship, the Jamaat e Islami’s morally righteous slogan, ‘Pakistan Ka Matlab Kiya? La illa ha illAllah’ signified the replacement of Muslim modernism by Islamic nationalism and the reengineering of a South Asian identity towards the Arabisation of Pakistan. The pro-democracy and women’s movements countered religio-nationalist rhetoric of the ‘90s with subversive slogans like, ‘Pakistan Ka Matlab Kiya? Laathee, Gollee, Martial Law’ and ‘Chacha Wardee Lahenda Kioun Naiee, Pension Lay Kay Janda Kioun Naiee?’

Today, not just dissenting bodies but even abstract slogans are being rendered as anti-state. We can scoff at the absurd anxiety that mere rhetoric can cause but it is symptomatic of a deeper unease within the military after the war on terror and Musharraf’s trial and what Habermas termed, the ‘legitimacy crisis.’

There are many historic examples of defiance against the state’s hegemony but the reason for the current national despair is the realisation that, not only is this now in short commodity but all state pillars are on the same page - number 1999. Military rule and democracy, western neoliberal economies and religious politics, and civil society and the state are not in conflict or in the mood to exercise checks and balance.

The tribal areas that were already not pre-modern for a long time, are merging into the postcolonial state and have to be tamed within the existing state arrangement. Ironically, for a generation of millennials who have postcolonial studies oozing from their keyboards, no one is interested in influencing the structural aspects of this transition beyond ‘supporting’ the charismatic anti-hero of the state, Manzoor Pashteen.

The not so high moral ground

It is admittedly both romantic and thrilling to support dissent in these dark times. The young radicals of the PTM are admirably and eloquently exposing the state’s historic misadventures and demanding secular correctives to the religio-militancy inflicted by the Taliban and the state in FATA. The secular nature of the PTM’s undertaking confounds the establishment which is only accustomed to using religion as a driver of state narrative.

The other complication is that Pashteen, Dawar and Ali are playing by the rules of national politics in promoting their legitimate, democratically representative demands. Unfortunately, it is bad timing for democratic secular politics and at some point soon, the PTM will have to review its endgame.

Despite the malaise of cooperation or even co-optation by military regimes, women activists who infiltrated or held some interface with the state, deserve credit for extracting visible results and influencing tremendous progress for women’s rights in policy and practical terms. Similarly, several leading lawyers who dissented against Musharraf went on to become judges and attorney generals, while others continue to represent state parties. Many leaders of the ‘principled Left’ readily partake of state projects or are well-tenured in neoliberal academia. The ideological ground from where progressive critics launch their defiance, especially against the state, is never really very high nor far.

When all other movements have made compromises, struck deals, negotiated NROs and found corner offices within the Pakistan state, is it fair to expect the PTM youth movement to age with no concessions? How long will they sustain being at the receiving end of the ego and vengeance of a state that is looking for new enemies for the sake of its own survival and legitimacy?

Self over sovereignty

Sovereignty is a fickle commodity. Prime Minister Imran Khan is so blinded by a self-preserving political bloodlust that with no embarrassment, he reinforces clear conflict of interests and compromises national sovereignty through his appointments to government and state offices. Compare the PTI’s hiring of non-resident and has-been technocrats from the ‘treacherous’ and ‘corrupt’ governments of the PPP and Musharraf, and its import of a serving IMF official as governor of the state bank, against the moral outrage for our threatened collective ‘national honour’ in the cases of Raymond Davis, the Kerry Lugar bill, drone-warfare, and Memogate. Odd, how statesmen like Shahzad Akbar and Shah Mehmood Qureshi who crusaded against such causes seem to have lost their self-righteous appetite for ‘state sovereignty’ now that they are in power.

It may be time for young leaders of the PTM to assess the risks of being the bait of obsession for the state machinery and its hypocritical stage-managers in government. There may be wisdom in seeking a principled yet, effective way to extract the best possible concessions from a state that is not withering away any time soon. It is too much to hope that this state will listen, heal, allow people to develop narratives of dignity and, instead of blaming the external, reflect on its own role in causing antithetical sentiments towards the state.

The writer is the author of Faith and Feminism in Pakistan, and can be contacted on afiyaszia@yahoo.com

Anti-state anxiety attacks

Since the very birth of Pakistan was in the form of a monozygotic split of West and East, the state versus anti-state tension was perhaps predictable. But even after the political separation of physically and culturally unconnected lands, state-belonging in Pakistan continues to depend on linguistic, ethnic and religious differences. Only gender and class serve as more stable levers that determine state access and patronage.

Under ZA Bhutto’s rule, the distant Bengalis were easier to suspect as prone to sedition, while the intimacy of Ahmedis made it necessary to reinvent them as counterfeit citizens. In Zia ul Haq’s time, women, socialists and Sindhis were condemned as westoxified, godless anti-nationalists. The status of the Baloch, Pakhtuns and Mohajirs has depended on the political and economic contracts that they have brokered or broken with the rentier state.

A little dissonance maintains the image of a magnanimous state that gives its people ‘agency’ – to vote, pray, disagree within approved parameters, or collect some charity. But agency is not opposed to power, which is a commodity jealously guarded by our state that, in turn, is never neutral. To successfully claim rights or wrest a share of resources or powers that are monopolised by the state – either in the form of hard cash or simply, the license to use violence as a means of income or political power - you have to be a patron, benefactor, or proxy of this state.

Exceptionalism and escape

The law of state exceptionalism allows selective forgiveness - for Munawar Hasan but not Hussain Haqqani, for Junaid Jamshed but not Asia Bibi, for Zaid Hamid but not Zahid Hamid, for General Musharraf but not Nawaz Sharif, even for the Tehrik-i-Taliban and Noreen Leghari, the would-be ISIS recruit, but not for Alamzeb the PTM activist in jail, and so on.

The proximity argument holds more weight when we consider how the state has historically sponsored jihadist proxies. Some jihadist outfits and their madrassas are protected as patriotic defenders of the Islamic Republic while others are scheduled as anti-state. Their positions on the list of banned outfits fluctuates as much as the KSE these days. Although the anti-state actor is cast as spurious, hostile and dangerous, there is salvation if he is willing to be de-radicalised and rehabilitated into the fabric of national compliance.

The term ‘actor’ accurately defines how nationalism is a performance (think, Hamza Abbasi) and the ‘non-state actor’ is easier to identify due to his disruptive attacks on the state. But how do so many activists, reformers, intelligentsia and those ubiquitous ‘concerned citizens’ who are constantly pressurising the state to ‘do more’, relinquish rights and privatise itself, manage to escape the anti-state label?

All through the Musharraf regime, the entity that came to call itself ‘civil society’ (including the fourth estate, the media), and that is ostensibly a watchdog of the state, actively embraced and enabled this ‘liberal’ military dictator. For a decade, we witnessed sycophantic fashion designers tailoring the emperor’s robes, and servile organisers of film and culture festivals hosting ribbon-cutting ceremonies for the military usurper. We witnessed fawning film-makers document their dinners with a dictator and opportunistic activists participate in policy-making and elections that fortified a military regime. Pliant bureaucrats would jump with excitement if the uniformed ‘CEO’ turned up to a civic event, and Janus-faced journalists extended the coup-maker their sympathy as the country protested on the streets. Always ready to fiddle with Nero, a facile bourgeoisie swayed along to the political melody played for the adventurist architect of Kargil at countless balls and Qawali mehfils.

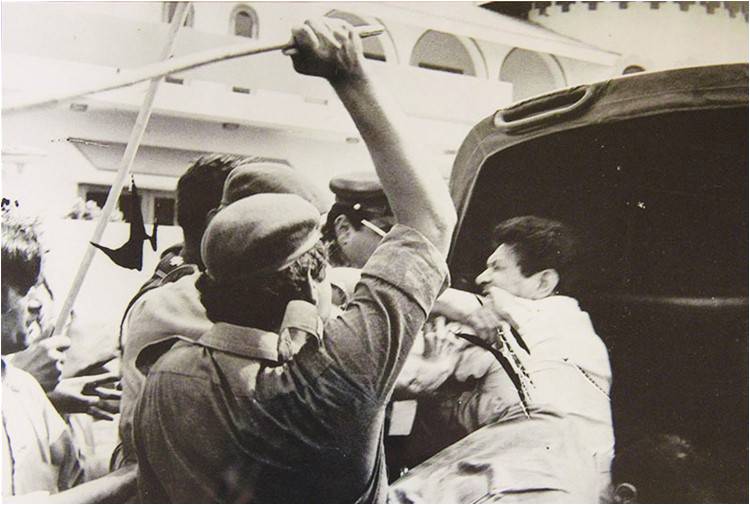

Slings, arrows and slogans

If the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and the women’s movement were the courageous forces of resistance against General Zia’s brutal regime, then the only challenge to General Musharraf’s praetorian rule was from the Lawyers Movement. However, the legacies of these battles have been mixed. The women’s movement of the 1990s fragmented into NGO-led projects and lost its radical edge, and the Lawyers Movement is often undermined retrospectively, as one co-opted by the intelligence agencies.

The point here is not about the compromises of resistance movements but to assess the options they faced after their rise against the state. Today, the PTM is the only force of defiance against this Sisi-like, military-led civilian rule. When the state changes its game, so must the politics of resistance.

Under ZA Bhutto, the materialist slogan ‘Roti, Kapra Aur Makaan’ resonated with a global wave of welfare socialism. Under Zia ul Haq’s dictatorship, the Jamaat e Islami’s morally righteous slogan, ‘Pakistan Ka Matlab Kiya? La illa ha illAllah’ signified the replacement of Muslim modernism by Islamic nationalism and the reengineering of a South Asian identity towards the Arabisation of Pakistan. The pro-democracy and women’s movements countered religio-nationalist rhetoric of the ‘90s with subversive slogans like, ‘Pakistan Ka Matlab Kiya? Laathee, Gollee, Martial Law’ and ‘Chacha Wardee Lahenda Kioun Naiee, Pension Lay Kay Janda Kioun Naiee?’

Today, not just dissenting bodies but even abstract slogans are being rendered as anti-state. We can scoff at the absurd anxiety that mere rhetoric can cause but it is symptomatic of a deeper unease within the military after the war on terror and Musharraf’s trial and what Habermas termed, the ‘legitimacy crisis.’

There are many historic examples of defiance against the state’s hegemony but the reason for the current national despair is the realisation that, not only is this now in short commodity but all state pillars are on the same page - number 1999. Military rule and democracy, western neoliberal economies and religious politics, and civil society and the state are not in conflict or in the mood to exercise checks and balance.

The tribal areas that were already not pre-modern for a long time, are merging into the postcolonial state and have to be tamed within the existing state arrangement. Ironically, for a generation of millennials who have postcolonial studies oozing from their keyboards, no one is interested in influencing the structural aspects of this transition beyond ‘supporting’ the charismatic anti-hero of the state, Manzoor Pashteen.

The not so high moral ground

It is admittedly both romantic and thrilling to support dissent in these dark times. The young radicals of the PTM are admirably and eloquently exposing the state’s historic misadventures and demanding secular correctives to the religio-militancy inflicted by the Taliban and the state in FATA. The secular nature of the PTM’s undertaking confounds the establishment which is only accustomed to using religion as a driver of state narrative.

The other complication is that Pashteen, Dawar and Ali are playing by the rules of national politics in promoting their legitimate, democratically representative demands. Unfortunately, it is bad timing for democratic secular politics and at some point soon, the PTM will have to review its endgame.

Despite the malaise of cooperation or even co-optation by military regimes, women activists who infiltrated or held some interface with the state, deserve credit for extracting visible results and influencing tremendous progress for women’s rights in policy and practical terms. Similarly, several leading lawyers who dissented against Musharraf went on to become judges and attorney generals, while others continue to represent state parties. Many leaders of the ‘principled Left’ readily partake of state projects or are well-tenured in neoliberal academia. The ideological ground from where progressive critics launch their defiance, especially against the state, is never really very high nor far.

When all other movements have made compromises, struck deals, negotiated NROs and found corner offices within the Pakistan state, is it fair to expect the PTM youth movement to age with no concessions? How long will they sustain being at the receiving end of the ego and vengeance of a state that is looking for new enemies for the sake of its own survival and legitimacy?

Self over sovereignty

Sovereignty is a fickle commodity. Prime Minister Imran Khan is so blinded by a self-preserving political bloodlust that with no embarrassment, he reinforces clear conflict of interests and compromises national sovereignty through his appointments to government and state offices. Compare the PTI’s hiring of non-resident and has-been technocrats from the ‘treacherous’ and ‘corrupt’ governments of the PPP and Musharraf, and its import of a serving IMF official as governor of the state bank, against the moral outrage for our threatened collective ‘national honour’ in the cases of Raymond Davis, the Kerry Lugar bill, drone-warfare, and Memogate. Odd, how statesmen like Shahzad Akbar and Shah Mehmood Qureshi who crusaded against such causes seem to have lost their self-righteous appetite for ‘state sovereignty’ now that they are in power.

It may be time for young leaders of the PTM to assess the risks of being the bait of obsession for the state machinery and its hypocritical stage-managers in government. There may be wisdom in seeking a principled yet, effective way to extract the best possible concessions from a state that is not withering away any time soon. It is too much to hope that this state will listen, heal, allow people to develop narratives of dignity and, instead of blaming the external, reflect on its own role in causing antithetical sentiments towards the state.

The writer is the author of Faith and Feminism in Pakistan, and can be contacted on afiyaszia@yahoo.com