Horizontally Weak

Uprisings, especially in the shape of mass protests, become bandwagons that the media and amoral political forces jump on. While on it, they exhibit unabashed excitability and roll out finger-wagging lectures packed with moral and alarmist platitudes against the 'powers that be.' It is only after the uprisings fail (and most do) that political scientists and commentators begin to produce more realistic studies of the protests.

In October 2023, a book If We Burn, by the American journalist Vincent Bevins began to gather a lot of traction among political/social activists. The thesis of Bevins' book is shaped by his first-hand experiences as a foreign correspondent for various American and British newspapers. In the 2010s, he covered multiple uprisings — especially in the Middle East, Brazil, Ukraine, Hong Kong, Tunisia, South Korea and Turkey. A majority of these uprisings were being navigated by leftist and liberal groups.

Bevins confessed that the media did not fully understand the volatile nature of the uprisings. It was only later that Bevins understood the uprisings were bound to fail because most of them repeated the mistakes of some past (failed) uprisings. The biggest mistake, in Bevins' view, was the postmodern nature of the protests. They were largely moulded on 'horizontal' lines or in which there are no decision-making hierarchies, and everyone involved is 'equal.' Many political scientists, too, have claimed the same. But perhaps Bevins' most startling conclusion is that horizontal uprisings end up triggering the opposite of what they actually set out to achieve.

Except the uprisings in South Korea and in Tunisia in the 2010s, which somewhat managed to trigger more fruitful outcomes, the other uprisings that Bevins covered crashed and burned. According to Bevins, the structural holes that these mass protests managed to create were quickly filled by the more vertically organised (right-wing) forces, and by the state itself.

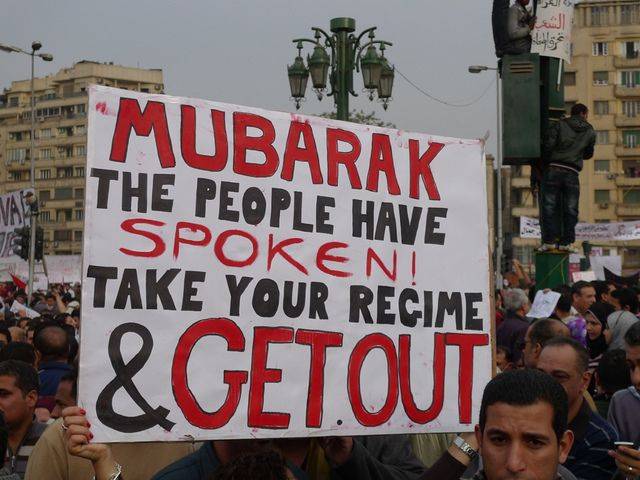

For example, in 2011, mass protests in Egypt succeeded in greatly upsetting the status quo. The uprising forced a dictator, Hosni Mubarak, to resign. But there was no organised party or coalition among the protesters capable of filling the vacuum created by the dictator's departure. Elections were held after his fall. These were won by perhaps the country's most organised party, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). An established Islamist outfit, MB had entered the protests at a much later stage. The protests were mostly propelled by leftist, liberal and 'moderate' groups and individuals. MB was a late entrant.

Uprisings organised along horizontal lines have their roots in the 1960s' student uprisings in the US and Europe

The demands of the protesters included police reforms, an end to the dictatorship, and the introduction of 'actual democracy.' Yet, when democracy was introduced in the vacuum that was created by the protests, the horizontal nature of the protesting groups meant that no single group or even a coalition of groups, was able to come together and fill it. Only MB had the kind of vertical structure needed to organise a focused election campaign and have a cohesive message. The leftist and liberal vote, and most of the moderate votes, were scattered among multiple other parties. This scattering handed the MB a decisive victory.

Yet, MB struggled to fill the vacuum. The party's opponents saw it as an opportunistic outfit that had come to power by 'exploiting' the 'struggle' of groups who had been the most prominent players in the protests. What's more, many such groups had gone out of their way to insist that the protests were about establishing democracy and not an Islamist alternative. But didn't MB come to power through a democratic process? The problem was that, unlike the decaying dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak, whose growing unpopularity had united diverse groups of people during the protests, MB was a polarising force due to its overt Islamist programme and history.

In 2013, the MB regime, too, began to face protests, just a year after being elected. It was accused by its opponents of authoring a constitution that gave President Mohammad Morsi' dictatorial powers.' Ironically, the anti-Morsi protests included many groups who were part of the anti-Mubarak protests as well. When the protests turned violent, the country's powerful military establishment toppled the MB regime and declared martial law. In another irony, many groups who had succeeded in pushing out Mubarak, hailed the coup. It was equally ironic when those hailing the coup also set fire to photographs of the then US President Barak Obama and the US ambassador in Egypt at that time.

Whereas Mubarak was seen as a US puppet, MB's Morsi began being seen (by his opponents) as someone 'planted by the US on the behest of Israel.' The military stepped in to address the 'growing polarisation' and 'confusion' in the country. It ejected MB from the vacuum and filled it with an authoritarian regime led by a 'popular' military and anti-Islamist general. Most liberal forces decided to support the general while the leftists remained dispersed.

Uprisings organised along horizontal lines have their roots in the 1960s' student uprisings in the US and Europe. For now, let's dub it as 'horizontalism.' As an idea and protest tool, it emerged from what came to be known as the 'New Left.' The New Left was an intellectual movement which deeply critiqued Marxism. It looked to expand Marxism's scope to address multiple issues which the movement bemoaned Marxists were either ignoring and/or had no interest in. These were mostly social issues such as racism, gender inequalities, and the marginalisation of vulnerable communities.

To the New Left, even when Marxism did address these, they were put in outdated and authoritarian contexts, as demonstrated by the 'totalitarian' regime in the Soviet Union and in 'communist' countries that were in the Soviet orbit. The New Left was suspicious of hierarchies which, it lamented, had given birth to 'elites' even in communist countries. Horizontalism greatly attracted the 1960s' generation of young men and women who had begun to confront the status quo through multiple sets of rather idealistic and even utopian ideas.

It quickly became apparent that horizontalism, too, was a utopian notion. It was the outcome of a highly romantic framing of unity and equality. Everyone was to become a leader in movements pitched against the 'exploitative and racist capitalist system.' In May 1968, student protests erupted in Paris. Universities became battlegrounds where students rioted against the police. France came to a standstill. University walls were plastered with posters of Marx, Mao and Lenin. The intensity and ferocious nature of of the protests were such that President Charles de Gaulle (a war hero) decided to leave the country.

Many French newspapers were abuzz with excitement. Editorials advised politicians to 'listen to the youth,' while others saw the 'making of another great French Revolution.' As reporters walked around university campuses looking for leaders and outfits leading the 'revolution,' they came across numerous young folk, some calling themselves Marxist-Leninists, some Maoists, some Trotskyites, anarchists, socialists, etc. There was no core leadership with a core message. There were multiple leaders with multiple agendas and messages.

The groups involved had their own ideas of democracy, socialism, etc. They were often ideologically hostile towards each other

No one could answer a simple question with any clarity. And that question was, 'What now?' A hole had been punched, and a vacuum had appeared after the president flew out of the country to somewhere in Germany. The military, concerned about the 'anarchy' created by the protests, lured the president back to France after guaranteeing him safety. de Gaulle at once announced fresh presidential elections, even though he did not contest the polls himself. A candidate backed by de Gaulle's party, the Union of Democrats of the Republic (UDR), won 58.21% of the total vote and the presidency.

So what happened? Hardly a month after France was supposedly 'on the brink of a revolution,' 58.21% of the electorate chose to vote for the same party that the 'revolutionaries' thought they had toppled. The truth was no coalition or outfit that was part of the protests united to challenge UDR. Different left and liberal groups had begun to vehemently disagree with each other after ousting the president. They had no cohesive message or programme to offer as alternatives. The conservative 'Gaullists' came charging back with a clear message ('stability'), and a party with a vertically visible leader. The Gaullists were, in fact, strengthened and went on to sweep the 1973 parliamentary elections as well.

The era of protests and student uprisings in the late 1960s (elsewhere in Europe and the US) produced similar results. They were organised horizontally; they had no single or unified leadership and no clear programmes other than wanting to end the war raging in Vietnam. The groups involved had their own ideas of democracy, socialism, etc. They were often ideologically hostile towards each other. One can call this leftist sectarianism. Yet, in the US and across many European countries, the protests did succeed in punching holes and seriously disrupt the status quo. But these holes were almost always filled by vertically organised (rightist) forces.

The US in 1968 too seemed to be on the brink of a social collapse, as mass student protests and riots set many of the country's streets and campuses ablaze. But in November 1968, it was the Republican Party candidate Richard Nixon who won the presidential election. In 1972, he won again, this time by a landslide. In the book Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, historians Maurice Isserman and Michael Kazin wrote that 'the left blazed through the Sixties like a meteor, reshaping the cultural landscape, particularly in the areas of gender and race … [but it was] the Right that established itself as a unified and potent political movement during the same decade.'

Groups on the right had no qualms about allying themselves with mainstream parties on the right, such as the Republican Party, whereas leftist groups refused to do the same with even the more left-liberal wings of the Democratic Party. In fact, in April 1968, radical left groups rioted outside a Democratic Party convention in Chicago. Instead of strategically supporting the Democratic Party to keep Nixon out, the left plunged into offering nothing more than amusing spectacles. For example, a radical left outfit called the 'Yippees', ran a pig as its candidate for the 1968 presidential election!

Opening doors for the right

The postmodern left that was given birth by the New Left could never overcome its romance with leaderless movements and uprisings. It shunned the vertical organisational mechanisms developed and propagated by classical communist ideologues such as Vladimir Lenin. This is why, even when and if, after succeeding to punch holes in a hated ruling structure, the postmodern left fails to produce a cohesive strategy or any cohesive programme. It just becomes a spectacle — one which may disturb the status quo but quickly scatters and recedes. The more organised forces on the right take advantage of the opening created by the left.

Unlike student uprisings in Europe and the US, most protesting student groups in Pakistan decided to ally themselves with two major parties

In 2013, various radical left groups organised rallies against the rise of bus fares in the Brazilian city of São Paulo. Brazil had a social democratic government at the time. The mayor of São Paulo was sympathetic towards the protesters and agreed to accept their demands. But the rallies became even larger and then turned violent. The media jumped in and began to lecture the government on how to resolve the issue. According to Bevins, during the initial stages of the protests, the media had not taken them seriously. But once they began to expand and confront the police, the protesters were dubbed as 'patriots' by the media.

As the horizontal left began to scatter, organised far-right groups jumped in, and the rallies became protests against 'corruption'. According to Bevins, these protests went a long way in popularising the anti-corruption narrative which triggered vertically organised right-wing protests in 2015, and the eventual rise of the populist Jair Bolsonaro who ousted the socialists by winning the 2018 presidential election. He received 55.13% of the total vote.

In 1968, leftist/progressive student groups kickstarted a protest movement in Pakistan. Their target was the Ayub Khan dictatorship that had been in power since late 1958. The anti-Ayub movement quickly spread in both wings of the country, West Pakistan and the erstwhile East Pakistan. Unlike student uprisings in Europe and the US, most protesting student groups in Pakistan decided to ally themselves with two major parties: The secular Bengali nationalist Awami League (AL) in the East, and the rapidly expanding left-leaning Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) in the West.

The student movement in Pakistan was, therefore, more organised. It adjusted its aims and programmes according to those of the AL and PPP. Many student outfits merged with the two parties. The parties had more resources and experience to navigate the movement in such a manner that not only was Ayub forced to resign, but the next general, Yahya Khan, was successfully pushed to hold the country's first major parliamentary elections in 1970.

What's more, many student leaders who had either allied themselves with PPP and AL, or had joined them, were given party tickets to contest the elections. Some actually won and were appointed as ministers, while some were brought in as advisors. Indeed, East Pakistan broke away in December 1971 after a brutal civil war, but an elected government came to power in West Pakistan, which, of course, was now the only Pakistan. The PPP had won the largest number of seats in West Pakistan and thus enjoyed a majority in the new National Assembly. It was also able to form governments in two of the country's largest provinces, Punjab and Sindh.

By 1974, many young leftists, who had allied themselves with the PPP, began to criticise the ruling party for diluting its 'socialist' agenda, and becoming authoritarian. Nevertheless, at least, these leftists had managed to fill the vacuum that their protests had created. But they could not have done this without allying their groups with a vertically organised mainstream political party. Learning from this experience, many leftists tried to once again ally themselves with major parties during the 1977 protest movement against the PPP regime. But here's the catch: Unlike the 1968 movement, this movement was largely being navigated by Islamist parties.

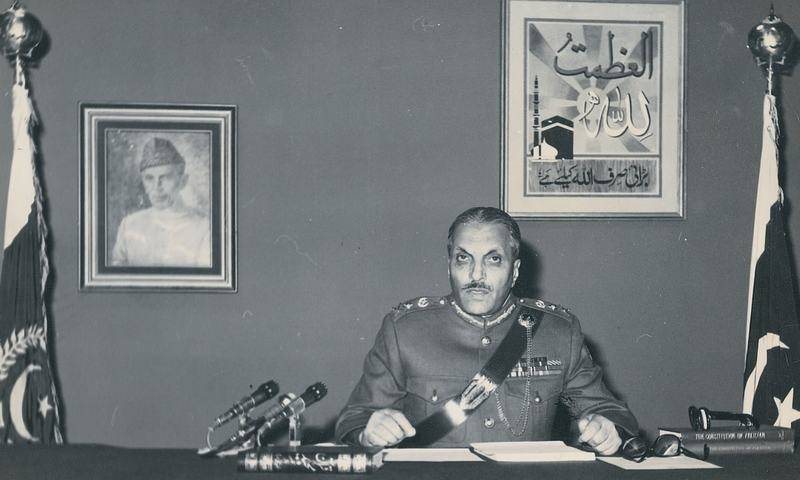

The anti-PPP leftists and progressives who participated in the 1977 movement completely misread the situation. The movement's initial demand was the nullification of the results of the 1977 elections that the PPP swept, but the opposition alliance alleged were 'rigged.' The leftists were predicting the coming to power of a coalition government after a fresh election, of which they, too, would become a guiding part. Something like the centre-right coalition that had come to power in India after the March 1977 elections. But as the anti-PPP movement intensified, the Islamist parties in the alliance became more prominent. Being better organised, they succeeded in turning the protests into becoming a movement for Nizam-e-Mustafa (Sharia rule).

The movement had forced the regime to retreat. The retreat created space which the Islamists ought to have occupied, but it was the even more organised military establishment which jumped in and occupied this space. Yet another military dictatorship was installed. It usurped the movement's Islamist overtones and remained in power till August 1988.

The post-80s horizontal left in Pakistan — scattered among tiny socialist groups — has faced embarrassing defeats in multiple elections. They somehow believe that their vote-bank is continuously being usurped by mainstream parties

During the 1980s, many leftist groups returned to support the PPP during the three major anti-dictatorship movements (1981, '83, '86). But this was the Pakistani left's last hurrah. After democracy returned in 1988, and the PPP was thrust back in power, this is when the left went horizontal.

However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, though, some major figures from the left decided to formally join mainstream parties. For example, one of the founding members of the left-wing Sindh National Students Federation (formed in 1968), Jam Saqi, quit a faction of the Communist Party of Pakistan in 1991 and joined the PPP.

During the last three decades, multiple leftist outfits have appeared, disappeared and, reappeared and disappeared again. They have little or no influence at all, or the kind of pull that they had till 1988. Due to some inexplicable reason, they refuse to ally themselves anymore with mainstream left-leaning parties. The post-80s horizontal left in Pakistan — scattered among tiny socialist groups — has faced embarrassing defeats in multiple elections. They somehow believe that their vote-bank is continuously being usurped by mainstream parties such as the PPP and by the Pakhtun and Baloch nationalist parties. This is really a delusion. But this hasn't stopped them from lending support to Islamist parties opposed to the PPP in Sindh, and right-wing populist parties such as the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in Punjab. As an outcome, they themselves have become the opposite of what they set out to achieve.