In 1958, Raymond Williams published an essay titled “Culture is Ordinary.” The purpose of this essay was to challenge the elitist and highbrow perceptions of what is considered art. He argued that culture is found at every stage of social hierarchy, in instances as mundane as a mother dropping off her child to school. The accumulation of everyday life is just as much culture as the literary and artistic expressions pondered upon by the very privileged in enclosed rooms.

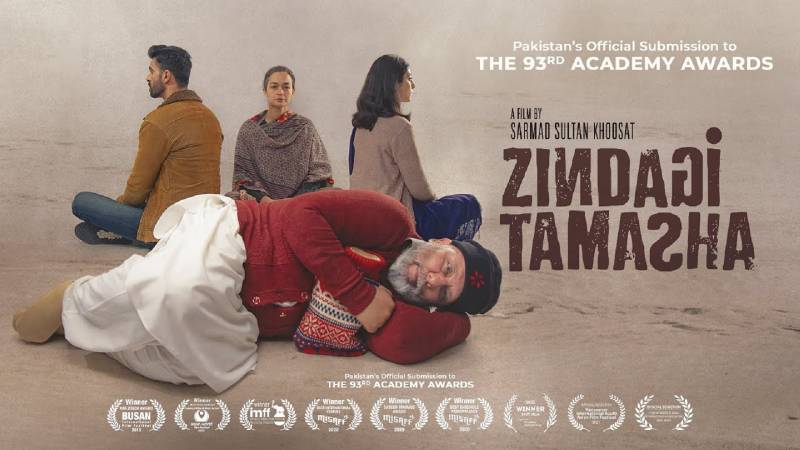

Sarmad Khoosat’s most recent directorial venture, Zindagi Tamasha, is an embodiment of William’s ordinary culture. Pakistan's entry for the Best International Feature Film at the 93rd Academy Awards, the film revolves around the stigma of shame and taboo of an old cleric whose dancing video goes viral, repudiating his years of work as a respectable, religious member of society. His crime is that he let his guard down amongst his closest old friends and danced in an effeminate manner. In a society that takes pride in the rigidity of its gender norms, there is no room for forgiveness. Even if it was a private setting and his act was not meant for public consumption, the fact that an old man was caught dancing and imitating an enticing woman means that he must be cancelled. His life, his achievements all amount to nothing. He is socially ostracised to the point of being abandoned by his own daughter. The protagonist’s very palpable inability to breathe is felt across the screen.

Despite all the censor board approvals and certificates, the film was not allowed to release in Pakistan, as it highlights the bigotry of the very powerful religious clergy. After legal battles on multiple fronts, the director, Sarmad Khoosat released the film on YouTube. He gave his account details in the description box of the film and left it to the viewer’s discretion if they wanted to pay for the cinema’s ticket. It is a small, independent production house operating, trying to bring stories and characters to life, and so, from their perspective, any support would be appreciated.

Khoosat himself makes a compelling cameo in the film, being his most vulnerable self in front of the camera. I hope Pakistan as a nation can honour its cultural icons in the zenith of their professional glory by facilitating their artistic expressions. The state cannot remain ‘neutral’ anymore, it must actively support its artists if it wants to preserve whatever iota of culture outlets are left.

We find that Khoosat’s effortless story telling is a genre of its own. The characters unfold in front of your eyes without any big confrontational dialogues or melodramatic sequences. There are moments of reformation weaved so beautifully into the story that it comes across as natural as it gets. It is life as we know it, subtle but impactful. The extraordinary vision of the writer, Nirmal Bano, can be seen in her ability to perceive a story from the most ordinary of circumstances around her.

This is an effort to humanise people that we confine to robotic characteristics.

In a close-knit society like Pakistan, one is apparently answerable to everyone around them. The private life must be a replication of the public life, and vice versa. No room to err, no room to be human. One can belong to the most dominant religious group, be a part of the clergy, or, for instance, enjoy all the perks of being a bourgeois - and yet be admonished if they dare to sway from the roles defined for them.

There is a beautiful sequence in the film where a clear demarcation is drawn between the Khwaja Sira community (Transgenders) and the mainstream society. All of them gather to watch the tamasha (circus) of Khwaja Sira being thrown out of their house and nobody publicly steps up to save them. Such is the circus of life; we all make a spectacle out of someone else’s suffering, not knowing that this can be us the very next minute. The protagonist’s humiliation stems from the public perception of who he is supposed to be. There is no question of infidelity or abuse of power in any capacity, yet the man is criminalised. Not by law, but by society.