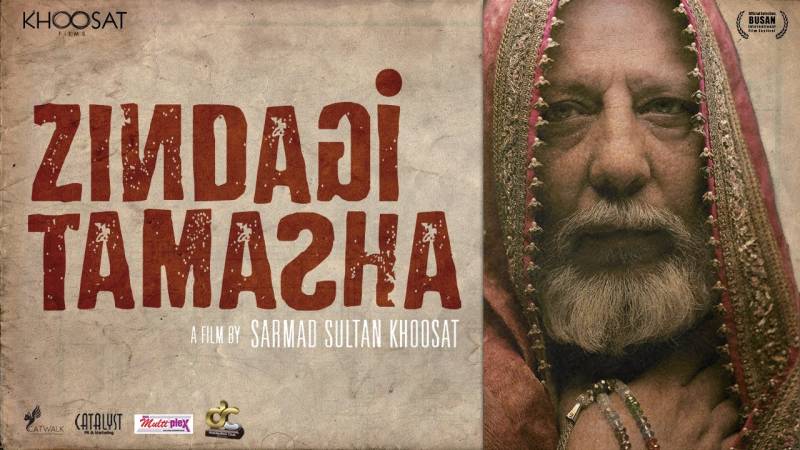

Sarmad Sultan Khoosat’s Zindagi Tamasha or 'The Circus of Life' (2019, Bussan & 2023, YouTube) is now available to the Pakistani audience. Despite the release certificate issued to the film by the Punjab Censorship Board in 2022, the film couldn’t be released in Pakistani cinemas, due to many controversies surrounding it. This article is an outcome of my discussion about the film with two London based filmmakers and academics – Parviin Karuna from India, and Dr. Baber Hussain from Pakistan.

A middle-aged man Rahat Khawaja is a devout Muslim and a naat khwa’an (reciter of poems in praise of the Holy Prophet PBUH), and a real-estate agent by profession. He has a flare for dance and music – something that according to society’s norms, is not acceptable for a good Muslim, particularly a naat khwa’an. The trouble begins when a video of Rahat’s dance, which he performed at the wedding of a friend’s son, goes viral. His daughter, Sadaf, a TV producer, feels ashamed of that video and confronts him. However, Rahat’s wife, who is on her death bed, remains a constant source of support for him, till her last breath. Living in the narrow alleys of the old city of Lahore means being a part of a closely knit social circle, which Rahat cannot escape. He is forced to record a video message by the Imam of the masjid in which he must apologise for his shameful act – the dance at the wedding. On the second take of the recording, Rahat bursts out in anger, as he is not ashamed of what he did. In extreme anger and disgust, Rahat reminds the Imam of stealing masjid charity funds for the construction of his house, and calls him a bacha baaz – a paedophile. This turns the Imam into his eternal enemy.

Barah Rabi-ul Awal arrives – the celebrations for the birthday of the Holy Prophet PBUH. Rahat prepares his naats and cooks niyaz (the food cooked and distributed among neighbors and friends, often a sweet dish) for the occasion. At the tent, where this naat event is taking place, the same Imam warns him to leave and threatens to provoke others against him. The Imam and his associates start reciting Darood-o-Salam (praise for the Holy Prophet PBUH), while giving him a dismissive stare. Rahat retreats with a heavy heart. Later, he takes his niyaz on a tray for distributing it to the neighbours. Nobody wants to take his niyaz, because he has fallen from grace because of his shameful indulgences. On this occasion, a eunuch steps forward, takes the niyaz tray from Rahat, and distributes it among the children in the street.

The tawaif or a randi, like the eunuch – and also Rahat Khawaja with his non-conformist attitude in Zindagi Tamasha, are born in a situation which they cannot change. They are born with a label, and are destined to die with it.

The eunuch’s noble and humane act on this occasion, raises a deeply political question. Khoosat’s film links with a recurrent theme in films and literature from the Subcontinent – what does it mean to be labelled a randi – a whore, or an immoral, licentious person? In a novel about the Partition of India, The Broken Mirror, Krishna Baldev Vaid has also raised this question. Set in LalaMusa, a town in western Punjab, the characters find themselves in a predicament as Partition unfolds. The violence that erupted from Rawalpindi has now travelled down to LalaMusa. Old friends – Hindu, Muslim and Sikh – who once dined and partied together, now start massacring each other. Amidst all this madness, Mumtaz Shanti – the randi, frequented by the Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims alike – proves to be the only humane and sane character in the town, just like Khoosat’s eunuch.

Likewise, there is Guru Dutt’s Gulabo in Piyasa (1957), who saves the protagonist’s life towards the end of the film, when he is declared an imposter and people are provoked to tear him into pieces. We have a long list of such characters from both Indian and Pakistani literature and cinema. For example, recall Rosie Marco in Vijay Anad’s Guide (1965), Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (1971), Hasan Tariq’s Umrao Jaan Ada (1972), and later Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan (1981).

All these films have raised that one fundamental question which Khoosat does in his own right – what does it mean to be a a vile and immoral woman/person? The tawaif or a randi, like the eunuch – and also Rahat Khawaja with his non-conformist attitude in Zindagi Tamasha, are born in a situation which they cannot change. They are born with a label, and are destined to die with it. Khoosat’s hero, Rahat, faces the same dilemma – his softer or feminine side, which he displays in his dance, despite being a devout Muslim. ‘God has always protected me from such immoral indulgences’, he yells out, when a young man from his neighbourhood takes him to an underground party.

What is the controversy here?

Parviin Kumar observed that in the tent scene, the filmmaker had an opportunity to balance the strong feelings created in the roof top scene, where Rahat’s apology is being recorded. The entry of an elderly, gentle, religious character in the tent scene could dispel the idea that the film aims to target all molvis – the whole lot of the clergy. By choosing to not do so, the filmmaker appears to have generalised that all of them are bad. This is a filmmaker’s suggestion to another filmmaker. However, it remains the director’s prerogative how he wants to portray his characters, and the way he wants to tell the story.

Dr. Baber Hussain was more interested in the last scene of the film. Sadaf, Rahat Khwaja’s daughter, visits her father to return her mother belongings, which she had taken after her death. She removes her necklace, and tells her father to wear it. From the start, she simply doesn’t approve of his dance and music, which she now holds responsible for her mother’s death – Rahat was sleeping with the TV on, and a film was running on loud volume, when his wife passed away. This was on the night of the tent incident. She is totally cross with her father for this very reason. This also shows a role reversal in the traditional patriarchal setup – the daughter wants to control her father, as she disapproves of his dance and music.

Shot mostly in the dark narrow alleys, the film has a grim and claustrophobic ambience. It also suggests the stifling conditions in which the protagonist finds himself.

In the closing shot, we see Rahat wearing his wife’s pink cardigan. Hussain was concerned whether the film endeavours to evoke sympathy and acceptance for the LGBT community through Rahat’s character. But it doesn’t appear to be the case. Rahat is not a gay man and there are no depictions of homosexuality in the film. Yes, his personality has a feminine side to it, but that too is only known to his old friends, and his wife had some idea about it.

Shot mostly in the dark narrow alleys, the film has a grim and claustrophobic ambience. It also suggests the stifling conditions in which the protagonist finds himself. The film leaves us with some questions that certainly unsettle already settled matters in Pakistani society: can’t a devout Muslim be into music and dance? The film also questions the religious authority vested in the hands of the clergy, who can use it for personal gains and for vendetta seeking purposes. In this sense, one can read the film as a purely political text.

Bill Forsyth, a celebrated British filmmaker, once said that a good film makes the audience come out of the theatre talking about it – Zindagi Tamasha has all the potential to do that.