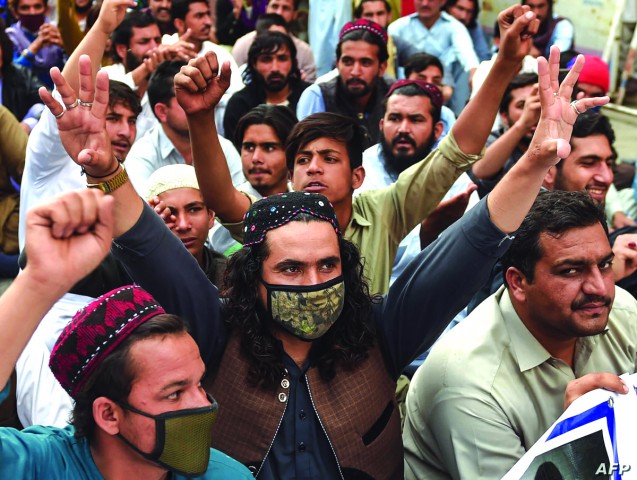

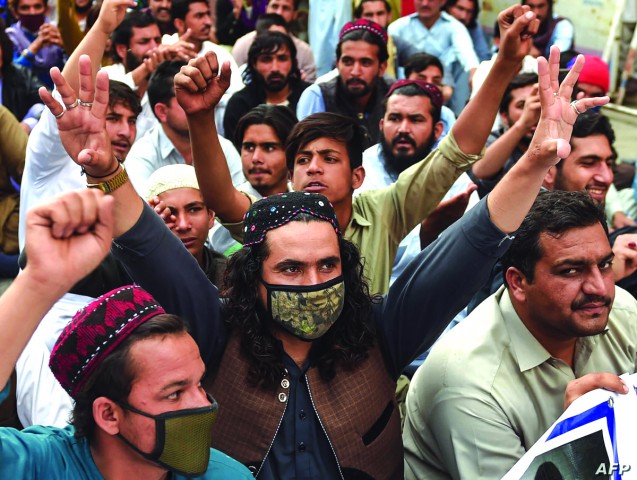

The Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) held a successful rally in Karachi on December 6th. This rally was quite different from the earlier PTM event in Karachi in 2018. It was distinct from other PTM rallies too, especially those happening in Pakistan’s heartland.

This PTM rally in Karachi went through smoothly, without the draconian repression which characterized its rallies elsewhere. The outward reasons for a relative lack of repression this time may be explained by the observation that the Powers That Be are heavily engaged elsewhere, i.e. in managing the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) – which is the opposition parties’ alliance aimed at the overthrow of the ruling regime through massive public gatherings.

However, what is of importance here is not the relatively safe environment in which a PTM rally happened in the mega-city of Karachi, but the fact that the PTM, even after years of its inception and surviving years of intimidation and brutal violence, still has the capacity to hold rallies and draw out crowds. And it can accomplish this even without without weeks of mobilization or capturing the attention of the liberal-left spaces on social media.

This rally happened not on the back of a wave of massive organizing effort, but instead on the basis of a novel narrative in a language whose vocabulary the mainstream of Pakistan wasn’t ready to use – or even familiar with.

It can be assumed now that in mainstream Pakistan’s political sphere, the PTM has stabilized its support among the liberal-left sections, small but vocal at times. But at the same time, PTM holds on to its organic base which consists of war-affected Pashtuns concentrated in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and southern parts of Baluchistan, but also distributed demographically across Pakistan via economic and political migrations.

In fact, PTM for the last few months is holding rallies in different parts of the Pashtun lands, and recently held a mammoth one in the epicenter of the war, Waziristan itself.

It wouldn’t be repetitive to point out that the PTM is articulating a consciousness which is born out of the pain inflicted by the continuous wars in wake of the so-called War on Terrorism.

The question arises as to how the PTM remains relevant and functional despite all the violence, intimidation and suppression by the state? What has the movement achieved so far that people still have faith in its program and the organization itself?

The recent mobilization by Manzur Pashteen and PTM in Karachi cuts to the heart of the faith in the politics and political consciousness represented by PTM. The movement is now three years old, as pointed out, with its program clearly defined and its working out in the open. By all means, it has its internal contradictions too, which are only to be expected in such a broad organic movement. But people flock to PTM not only in the periphery, where the oppression is naked and a revolutionary anger at the Powers That Be is the only relationship possible between the people and the state, but also in the urban metropolitan centres.

This integration of the periphery with the metropolitan through the bodies, lived realities and experiences of Pashtuns as the underclass facing structurally similar oppression, and an integral and single struggle, makes PTM a unique emancipatory movement of its kind. Just as the oppression Pashtuns face in Pakistan is spatially distributed (but also connected) so, too, is the political program and articulation of the consciousness born out of that spatial-structural discrimination by PTM. It’s a movement in a whole!

That the PTM represents an integrated response to the particular political oppression Pashtuns face across Pakistan also answers the question about what it has achieved so far and why it remains relevant. When there is a hybrid regime where the dictates of the security apparatus run the state’s policies and where a violent ethos define the national imaginary and the political project of the state, then the ability to form and organize on a different discourse in itself becomes a revolutionary act. But what the PTM has achieved so far is not only discursive. The principle of non-violence, which also informs the faith in a political consciousness connected to the everyday life and experiences of the masses, has been at the heart of the PTM’s appeal.

And it cannot be emphasized enough that the PTM’s appeal relies on the hope that the oppression will end. Hope is a revolutionary concept. The PTM appeals to the masses and to its organic base not only because it can articulate their everyday experiences and through it the masses express their anger, frustration, helplessness and pain – but also that through the PTM people can have a subjectivity, a political agency for the have-nots!

The PTM was written off: not once but many times. Often the internal contradictions (which are perhaps not contradictions per se but different visions about carrying the movement forward) are presented as the final endgame and there are predictions of implosion. But all these hopes of the Powers That Be, the security apparatus and the class that they belong to, not only not consider but also mock, erase and deny the power of feeling of the masses. It is more likely that the PTM will sustain any external suppression and any internal differences if it continues to reflect the structure of feelings and experiences of the masses who it draws its power from. And it is to the credit of the PTM that it goes back again and again to the masses to reaffirm its program and to continue the dialectical movement between everyday pain and its articulation in political consciousness. Because of the material conditions of the Pashtuns lands, and the reality of Pashtuns spread across the country, finding a single program which can capture the “diversity-in-unity” of the Pashtuns’ experience in Pakistan takes a vision which only a few are capable of – i.e. those who can be as “radical as reality itself.” Till now, with all its shortcomings and human failings, the PTM has been able to not only give but enlarge that vision.

The connection of the urban with the periphery is an analysis which often is missed in discourse on PTM. It is not because of any essential Pashtun quality that a movement which has to speak for all Pashtuns has a need to escape the ‘periphery’ (which is what the Pashtun lands have been turned into). Instead, it is because of the discriminatory economic policies and wars due to which Pashtuns have to migrate to the metropolitan core. The ability of the PTM to organize the Karachi rally, all on its own with a week or so of mobilization, proves that the metropolitan is not that far from the periphery. It posits that there is an intimate relation between the periphery and the mainland, on the level of political imaginary, which at times requires a clarity of vision and a belief in organic consciousness to translate into a political program.

This undying enthusiasm and faith in a movement whose arsenal and tactics consist of bare bodies and of willingness to subject these bodies to the brutality of state violence to expose the nakedness of the state’s exclusionary logic tells a story of making political subjects (with immense disruptive-emancipatory potential) out of a scattered people who were helpless against decades of barbaric oppression. A lot has been said and will be said about the emotive response to the PTM’s slogans, evocative rallies and heart-wrenching scenes at its events, but what remains the defining feature of the PTM (and its gatherings) is that it has given a voice to the voiceless.

It remains a story of the forcefully silenced finding their voice. And that is why it refuses to “go away.”

This PTM rally in Karachi went through smoothly, without the draconian repression which characterized its rallies elsewhere. The outward reasons for a relative lack of repression this time may be explained by the observation that the Powers That Be are heavily engaged elsewhere, i.e. in managing the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) – which is the opposition parties’ alliance aimed at the overthrow of the ruling regime through massive public gatherings.

However, what is of importance here is not the relatively safe environment in which a PTM rally happened in the mega-city of Karachi, but the fact that the PTM, even after years of its inception and surviving years of intimidation and brutal violence, still has the capacity to hold rallies and draw out crowds. And it can accomplish this even without without weeks of mobilization or capturing the attention of the liberal-left spaces on social media.

This rally happened not on the back of a wave of massive organizing effort, but instead on the basis of a novel narrative in a language whose vocabulary the mainstream of Pakistan wasn’t ready to use – or even familiar with.

It can be assumed now that in mainstream Pakistan’s political sphere, the PTM has stabilized its support among the liberal-left sections, small but vocal at times. But at the same time, PTM holds on to its organic base which consists of war-affected Pashtuns concentrated in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and southern parts of Baluchistan, but also distributed demographically across Pakistan via economic and political migrations.

In fact, PTM for the last few months is holding rallies in different parts of the Pashtun lands, and recently held a mammoth one in the epicenter of the war, Waziristan itself.

It wouldn’t be repetitive to point out that the PTM is articulating a consciousness which is born out of the pain inflicted by the continuous wars in wake of the so-called War on Terrorism.

The question arises as to how the PTM remains relevant and functional despite all the violence, intimidation and suppression by the state? What has the movement achieved so far that people still have faith in its program and the organization itself?

The recent mobilization by Manzur Pashteen and PTM in Karachi cuts to the heart of the faith in the politics and political consciousness represented by PTM. The movement is now three years old, as pointed out, with its program clearly defined and its working out in the open. By all means, it has its internal contradictions too, which are only to be expected in such a broad organic movement. But people flock to PTM not only in the periphery, where the oppression is naked and a revolutionary anger at the Powers That Be is the only relationship possible between the people and the state, but also in the urban metropolitan centres.

The ability of the PTM to organize the Karachi rally, all on its own with a week or so of mobilization, proves that the metropolitan is not that far from the periphery. It posits that there is an intimate relation between the periphery and the core, on the level of the political imaginary

This integration of the periphery with the metropolitan through the bodies, lived realities and experiences of Pashtuns as the underclass facing structurally similar oppression, and an integral and single struggle, makes PTM a unique emancipatory movement of its kind. Just as the oppression Pashtuns face in Pakistan is spatially distributed (but also connected) so, too, is the political program and articulation of the consciousness born out of that spatial-structural discrimination by PTM. It’s a movement in a whole!

That the PTM represents an integrated response to the particular political oppression Pashtuns face across Pakistan also answers the question about what it has achieved so far and why it remains relevant. When there is a hybrid regime where the dictates of the security apparatus run the state’s policies and where a violent ethos define the national imaginary and the political project of the state, then the ability to form and organize on a different discourse in itself becomes a revolutionary act. But what the PTM has achieved so far is not only discursive. The principle of non-violence, which also informs the faith in a political consciousness connected to the everyday life and experiences of the masses, has been at the heart of the PTM’s appeal.

And it cannot be emphasized enough that the PTM’s appeal relies on the hope that the oppression will end. Hope is a revolutionary concept. The PTM appeals to the masses and to its organic base not only because it can articulate their everyday experiences and through it the masses express their anger, frustration, helplessness and pain – but also that through the PTM people can have a subjectivity, a political agency for the have-nots!

The PTM was written off: not once but many times. Often the internal contradictions (which are perhaps not contradictions per se but different visions about carrying the movement forward) are presented as the final endgame and there are predictions of implosion. But all these hopes of the Powers That Be, the security apparatus and the class that they belong to, not only not consider but also mock, erase and deny the power of feeling of the masses. It is more likely that the PTM will sustain any external suppression and any internal differences if it continues to reflect the structure of feelings and experiences of the masses who it draws its power from. And it is to the credit of the PTM that it goes back again and again to the masses to reaffirm its program and to continue the dialectical movement between everyday pain and its articulation in political consciousness. Because of the material conditions of the Pashtuns lands, and the reality of Pashtuns spread across the country, finding a single program which can capture the “diversity-in-unity” of the Pashtuns’ experience in Pakistan takes a vision which only a few are capable of – i.e. those who can be as “radical as reality itself.” Till now, with all its shortcomings and human failings, the PTM has been able to not only give but enlarge that vision.

The connection of the urban with the periphery is an analysis which often is missed in discourse on PTM. It is not because of any essential Pashtun quality that a movement which has to speak for all Pashtuns has a need to escape the ‘periphery’ (which is what the Pashtun lands have been turned into). Instead, it is because of the discriminatory economic policies and wars due to which Pashtuns have to migrate to the metropolitan core. The ability of the PTM to organize the Karachi rally, all on its own with a week or so of mobilization, proves that the metropolitan is not that far from the periphery. It posits that there is an intimate relation between the periphery and the mainland, on the level of political imaginary, which at times requires a clarity of vision and a belief in organic consciousness to translate into a political program.

This undying enthusiasm and faith in a movement whose arsenal and tactics consist of bare bodies and of willingness to subject these bodies to the brutality of state violence to expose the nakedness of the state’s exclusionary logic tells a story of making political subjects (with immense disruptive-emancipatory potential) out of a scattered people who were helpless against decades of barbaric oppression. A lot has been said and will be said about the emotive response to the PTM’s slogans, evocative rallies and heart-wrenching scenes at its events, but what remains the defining feature of the PTM (and its gatherings) is that it has given a voice to the voiceless.

It remains a story of the forcefully silenced finding their voice. And that is why it refuses to “go away.”