A few days ago I was at the photo lab in my local grocery store, perusing the wall of faces and families.

This is the time of year when people take those quickie family portraits — those forced-feeling pictures of the kiddies to send to Grandma and Granddad for the holidays.

Looking at those faces made me think about my mother and her family’s tradition of taking annual photographs.

The ritual seemed so different back then and, as I discovered, had a much broader purpose.

My mother comes from the Bohra community in South Asia, which is a sub-sect of the Shia branch of Muslims.

In Pakistan and India, the Bohras are a small, insular and relatively wealthy community.

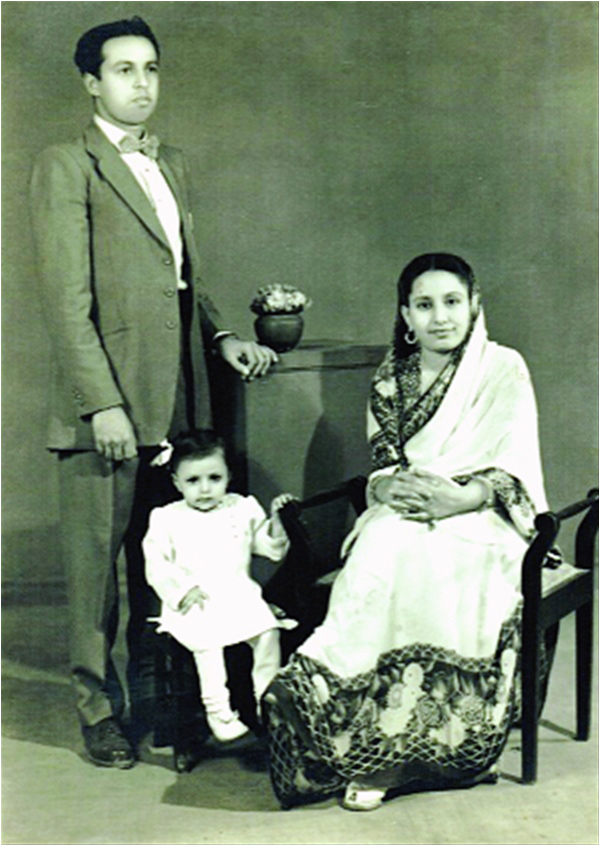

My maternal grandfather, Ghulam Abbas Tapal, was a big shot amongst the Bohras of Karachi both before and after the partitioning that created India and Pakistan in 1947.

He was a successful businessman who ran a lumber company — a man that people admired and, maybe, feared.

Every year, my grandfather took his family - my grandmother Rubab, my mom (the eldest), and their younger children - to have their photographs taken at Shangri-la Photo Studios in a busy market district of Karachi.

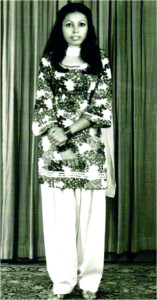

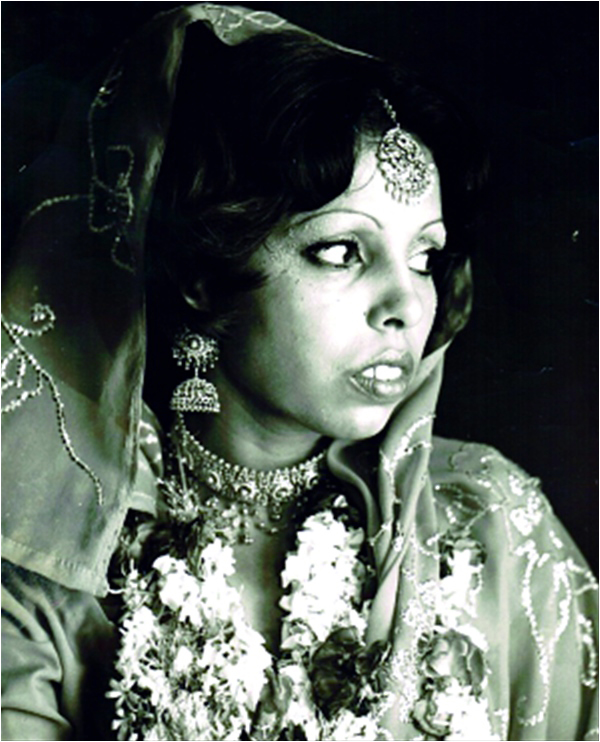

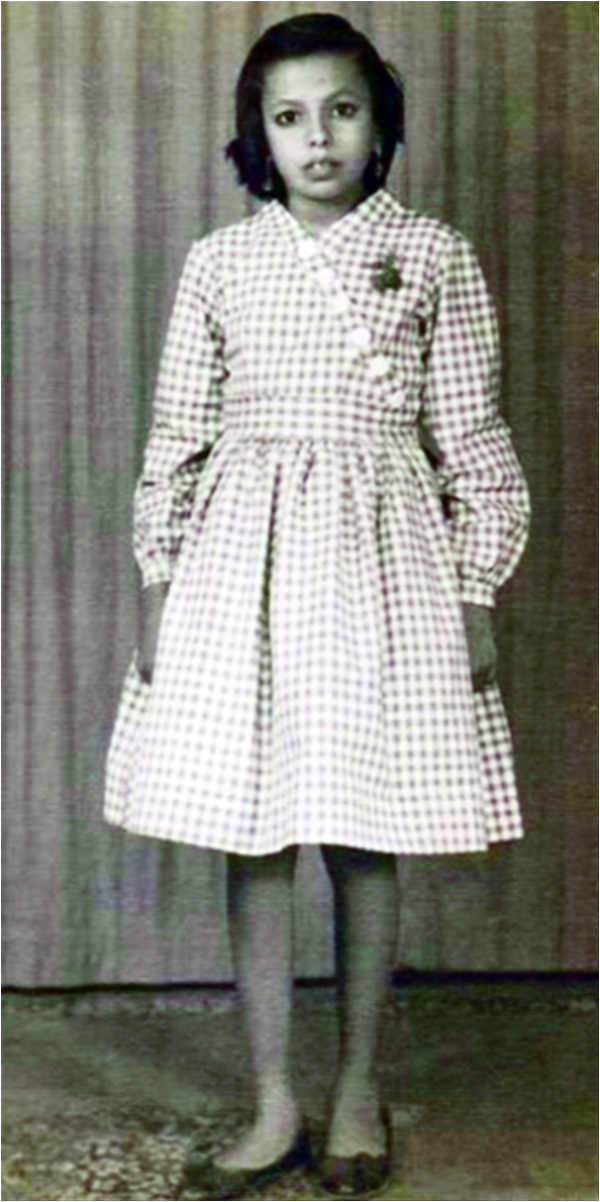

In my mother’s case, that meant that every year, from the age of one onwards, she would have her annual portrait taken.

My grandfather defied the rest of the community by continuing to go to the Shangri-la Photo Studios

Shangri-la was also run by a member of the Bohra community, a man I know only as Mr. Kerai. A short, dark skinned, bald man with a pleasant and shy manner.

His humble studio had a small reception area and big umbrella lights.

My mother doesn’t recall seeing an assistant, or a line-up at the studio, or even any other clients whenever they visited. The reason for that I discovered only this year.

The story goes that Mr. Kerai one day fell very ill and had to be hospitalised. It was in the hospital that he met an attractive young nurse with whom he fell in love.

In Pakistan and India, the Bohras are a small, insular and relatively wealthy community

There was one small problem. She was a Christian - not a Bohra, not a Shia, not even a Muslim.

Mr. Kerai was committing social suicide by falling for this girl.

And despite the warnings from his friends and family, he went ahead and married the pretty Christian nurse who had tended to him. They lived in a small house behind his photo studio and went on to have two daughters.

But their love came at a cost. Mr. Kerai’s family quietly estranged themselves from him and his wife, and never spoke to him again.

Word spread quickly in the Bohra community that the owner of the Shangri-la Photo Studios had married a Christian.

Nobody spoke to him about it directly, I was told. But Mr. Kerai and his wife were whispered about constantly at social gatherings.

As a result, Mr. Kerai lost not only his standing in the community, but almost all of his clients.

Now, my grandfather, as I mentioned earlier, was a man of local importance.

He was a reserved man, not political at all. But when he saw how Mr. Kerai was being treated, he defied the rest of the community by continuing to go to the Shangri-la Photo Studios.

Other photographers in the community wanted my grandfather’s business: they were eager to boast about having the Tapal family as their clients.

But my grandfather politely rejected those offers, waved off the gossip and stayed loyal to Mr. Kerai, even though he probably risked losing some social standing by frequenting the Shangri-la.

For more than 20 years, beginning in 1950, my mother and her parents went to Mr. Kerai for their family portraits. It is quite possible that they were the only Bohras who went there.

Even though Karachi is one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Pakistan, a financial hub and a seaport that has been open to the world for centuries, it is still a place where one’s clan matters.

My family’s photo habits changed only in the 1970s, when my mother went to university and met my father - a defiant socialist who criticized her for getting her picture taken every year like some sort of bourgeois princess.

At that point, she stopped going. Then her younger siblings stopped going and pretty soon the Tapals no longer went to the Shangri-la Photo Studios.

Shortly after that, Mr. Kerai shut down the business. It was the 1970s and many Pakistani Christians were moving to Canada for a better life. Mr. and Mrs. Kerai and their two daughters were among them.

This month, my mother turns 60 and she and I have been reviewing her life through Mr. Kerai’s portraits.

I don’t know where Mr. Kerai is today but he has given our family a great gift.

Not only did he document my mother’s change in age, fashion and hairstyle, but his pictures tell the story of my grandfather’s integrity.

When I look at those pictures I think about Mr. Kerai and my grandfather - two men who believed that love and honour come above all else. Two men who taught me that sometimes the story behind the picture is much more meaningful than the image itself.

This piece first appeared on CBC News online. It is being republished with the kind permission of the author, Natasha Fatah