Tahira Naqvi needs no introduction. An erudite, renaissance woman, deeply immersed in all aspects of what one might nostalgically call ‘Subcontinental’ literary culture, she is best known as the translator of Ismat Chughtai’s work, a labour of love she has been engaged in for the past many decades. As a newbie to the academic profession back in the 1990s, I was enamoured of both her translations as well as her short story collections—especially Attar of Roses—the latter harkening back to a time and place in the Beloved Country (Pakistan)—which I too, like Tahira, had left behind in the flush of youth’s desire to fly and discover new places, new passions.

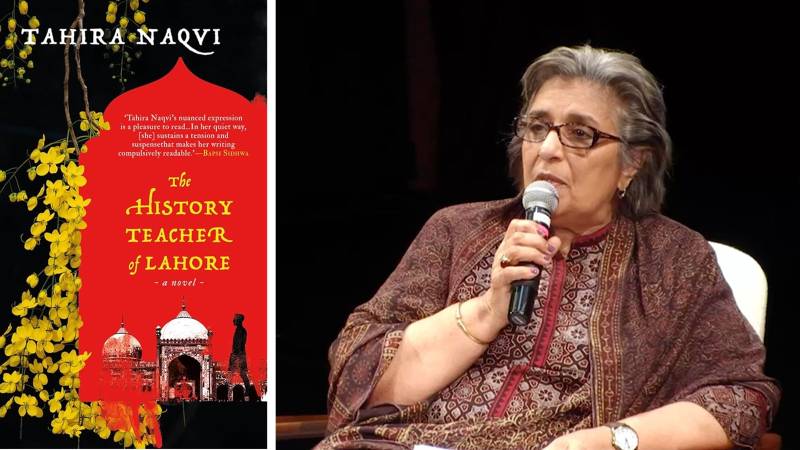

Now, with the publication of her brilliant debut novel, The History Teacher of Lahore (Speaking Tiger Press, 2023), peppered with epigraphs from Sartre’s writings especially his Age of Reason, Tahira Naqvi has produced a history of the people a la Howard Zinn, challenging the official state narrative taught in schools in Pakistan to cement the Islamist era ushered in by the government of General Zia-ul-Haq in the 1980s.

For lovers of both English and Urdu literature, readers immersed in philosophy and politics, this is a novel that asks an important philosophical question: who are we and how do we come to our commitments both political and personal? Herein we learn the truth of the feminist aphorism: the personal is the political. It is a hard-won lesson the eponymous history teacher learns, as too does the reader. A serious question raised in a serious novel of ideas by a woman of substance, a novel for our times. A question that asks us to make a choice, a moral choice: how do we wish to live, and thence to die?

Saloni Sharma reviewing the novel in The Scroll quotes Arif Ali, the History Teacher, who states: “literature and politics were like cousins courting each other and at any given time a marriage seemed imminent.” We might think of literature and its affect then, in the words of another great writer of the subcontinent, Arundhati Roy, whose work is the apotheosis of this union of the literary and the political, as “the space of shelter.” But the sheltering sky under which we as its readers gather in Naqvi’s novel, does not, unlike in the novel of this name (The Sheltering Sky) by colonialist writer Paul Bowles—expose us to dangers from savage “others” (Arabs in Bowles’ racist imagination)—but rather, to the dangers that lurk within us, within the bounds of identity limited by religion and nation, en/gendered by the post-colonial state. The shelter or solace that Naqvi’s novel provides is that of solidarity that sees in its Other a shadow of its own Self.

And indeed, this book lovers’ book, written for writers and aspiring writers and teachers too—is a veritable novel of ideas in the realist tradition of the 19th-century Russians, peopled with characters every bit as memorable and drawn as lovingly and with as much fine details as those in a novel or play by Tolstoy or Chekhov. And these are characters who like us, must decide what manner of human they wish to be! Like Palestinians who are choosing resistance over resignation, her characters too must make a choice: they must ask themselves, as the epigraph to one of her chapter’s reiterates:

“Better to die on one’s feet than live on one’s knees.”

These words sum up the shadow of Jean-Paul Sartre's Age of Reason that suffuses the novel, a novel that pays homage to a Pakistan that is vanishing, a Pakistan on which the Age of Jahilliya has begun to descend as the novel unfolds its painful history lesson, insisting we not forget this history as we move forwards into the present and future.

Part of the history recounted is tied to the beauty of open natural spaces and the gardens Lahore is rightly famous for, under threat as the novel opens, from “haphazard unplanned construction” and houses springing up everywhere decorated like “cheap pastry.” As chronicler of this multilayered history, Arif Ali observes how

“Jinnah Park, on the other hand, dotted with amaltas, shisham, and moulsari, and rows and rows of flowerbeds, had been spared this fate since it was a historical space. But for how long? All it took was a compulsive whim on the part of a standing government to scar history’s face.”

And of course, along with the nostalgia is embedded a critique not just of unplanned urbanization, but also the “scarring” of the entire nation state by the ugliness of religious and ethnic intolerance and extremism that was about to burst upon the scene, just as this young history teacher embarks on the beginnings of his adult life.

The nostalgia featured in the musings of the young history teacher includes references to Hollywood movies like Where Eagles Dare, starring Richard Burton, playing at the Plaza cinema on Mall Road one summer; for a reader of my generation, the reference unleashed a host of memories of teenage years, trying to get permission from strict parents to let us “girls” drooling over Burton and Peck and Niven, to go see such movies that excited us so! Sadly, the Plaza cinema is no more, just as the following scene, lovingly captured by Naqvi through the eyes of her narrator, now belongs in the history books, capturing “a whole way of life” (to quote Raymond Williams)—that has passed away:

“A tall, burly man and a woman in a black burka trudged by whispering to each other. A young man and a woman sat close together on the grass, the woman, her head covered with a brightly coloured dupatta, looking furtively around her as her companion whispered something in her ear, making her smile and blush. Some distance away two young boys, thirteen or fourteen, with restless, glinting eyes, were rolling kite string into a ball, a small, tattered kite lying beside them forlornly…”

It is a scene where the sacred and the profane mingle also, for as Arif Ali observes:

“In the background, Noor Jahan’s voice rang out in a sexy Punjabi song, while in the dhaba next-door rang out ‘shah-e-madina, shah-e-madina,’ the refrain invoking the Prophet.”

It is this homage to eclecticism of thought and being, to a co-mingling and co-existence of different spiritual and historical traditions and modes of living and experience, that bespeak Arif the History Teacher’s induction into the wide-ranging literary classics his mentor Kamal Ahmed introduces him to: from Rabindranath Tagore to Abdullah Hussain to Ibn-e-Safi via classic novels of the western literary tradition such as by Dickens and the Brontes ,and the philosophical treatises of Nietzsche and Sartre – these are all woven in to the novel as the warp and woof of our protagonist’s existence.

Thus, when he is first exposed to the lyrical words of Tagore’s text, Gitanjali:

“Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads!

Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark corner

of a temple with doors all shut?

Open thine eyes and see thy God is not before thee!

He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground

And where the path-maker is breaking stones.

He is with them in sun and in shower, and his

garment is covered with dust.”

The poem reminds him of the Punjabi poet Bulleh Shah’s verse:

“Bullah I know not who I am,

I am not of the mosque, nor the temple,

I am not among the pure, or amongst the impure

I am neither Moses nor the Pharaoh”

The novel’s characters and their daily existence—what Williams called in a different context, the very definition of culture as “a whole way of life”—this Pakistani cultural reality prior to its downward slide into fundamentalist thought, is revealed on the pages of the novel to be steeped in Sufi “ishq.”

The novel's nostalgia covers facets from the personal to the political, charming in taking us back the vista of years to half buried memories of love affairs conducted across neighbouring rooftops with Salmas and the Arifs of our own youthful pasts

In this regard, it is Kamal Ahmed who steals the show, who is in fact, the novel's real “love interest”—the standard-bearer of “ishq.” No one in his family had seen or heard from him in years till he suddenly reappears in Arif’s friend Sabir’s family home in Sialkot after the patriarch of the family passes away. Sabir’s grandfather had in a way, whilst alive, been the reason his son Kamal left and stayed away so long, both on account of his passion for books that prevented his pursuit of material (so-called) success, and also because he became involved according to Sabir, with a woman of “ill-repute.” This led to his being cut off from his inheritance and though offered his rightful share by his brother after the paterfamilias’ death, Kamal refuses the money. Described by Arif as a man who "was contemptuous of wealth…a man who refused a fortune”—Kamal Ahmed becomes (rightfully)the hero of the novel’s hero. We are told, “Arif’s admiration for him grew." Given the moral arc of the novel and of our hero’s own journey and growth, Kamal Ahmed’s code of conduct and personal values is itself also a throwback to a value system, of qualities one admired and looked up to in people, that sadly, exists rarely if at all, in the corrupt Pakistani society of today.

Indeed, the beating heart of the novel lies in the queer desire of Arif, the murshid, to be reunited with his pir, Kamal Ahmed, after the latter disappears once again from Sialkot in the middle of the night, leaving Arif feeling bereft and betrayed. Kamal Ahmed seems to have felt compelled to leave on a quest to save someone else, to answer the summons of a suffering “beloved” back in Lahore. It is only later that we, the readers, realize how this “beloved,” a woman named Nadira who hails from the Red Light area of Lahore—is not in need of Kamal’s saving. Rather, she is a saviour, side by side, equally, with Kamal Ahmed, in their joint quest to fight the forces of tyranny and religious intolerance that are descending on the country and rendering it unsafe for its religious minorities as well as women without patriarchal class protection.

Thus, when six years later, Arif stumbles upon Kamal in Lawrence Gardens (Bagh-i-Jinnah), he discovers an old love more frayed at the edges but strong in its denunciation of the rot of extremism masquerading as piety that had set into the fabric of society with the era of Zia-ul-Haq at the head of an increasingly corrupt army. The novel becomes a commentary on present day societal ills and the loss of decency and old-fashioned noble chivalry and heroic impulses embodied by the uncle: a writer, reader, activist dedicated to saving the lives of those unfortunates being targeted under the spate of vicious new laws.

Its nostalgia covers facets from the personal to the political, charming in taking us back the vista of years to half buried memories of love affairs conducted across neighbouring rooftops with Salmas and the Arifs of our own youthful pasts, an age of innocence trampled by the rise of the era of mullahs.

That era comes to be defined by blasphemy laws and the cruel havoc these wrought on Pakistan’s Christian and Ahmedi and Shia minorities. Arif first finds himself unwittingly roped into helping his idol Kamal and his friend/lover Nadira, of the Red Light district, in rescuing a young Christian boy, a student not unlike his own, whose father stands accused of blasphemy and hence the boy too is in the firing line of the mullah-inspired lynch mob. But as the following quote shows, it doesn’t take Arif long to understand and feel the tug at his heart, and his conscience, which will make him into a willing and even passionate, disciple of his pir.

"A gentle tug at his hand as they maneuvered a pothole made him look down at his ward. David remained quiet, his eyes apprehensive, his manner deferential. Of medium height, thin and handsome, his dark wavy hair cut short and combed back, he looked older than ten and could have been one of the students at Government Model School. His name could have been Kamal, Ahsan, or Kasim, he could be Muslim, Ahmadi or Shia, and his appearance would be the same. Arif wanted to shield him, to protect him not only now, but forever. At this moment there was nothing he wouldn’t do for the boy."

As Arif contemplates a bit later on:

"But uppermost on his mind was David. For some reason he felt he was complicit in society’s crime against the boy. He had not asked anything of Allah in a long time. Once home, Arif sat on a chair in his room, and closing his eyes, prayed for David’s safety, his thoughts continually returning to the boy’s quiet parting smile, his bewilderment at his circumstances, his helplessness."

Arif, much like Raju in RK Narayan’s popular novel (later a Bollywood film) The Guide, grows into the man he is meant to be, as a result of these haunting experiences: he transforms from being a follower, a murshid, into becoming a guide, a pir, his guiding philosophy, that of ishq.

As the novel winds to its disturbing conclusion, we see how it will be a while before the young can comprehend how a Mughal Prince Salim could love both Anarkali and later his wife, Noor Jehan, with seemingly equal passion and devotion. As Kamal Ahmed explains via the wisdom of poetry, "But, love is not a one-time affair...The beloved has a thousand facets, every facet a different colour/ I keep a specially chiselled diamond in my bosom.” In other words, we have to keep hope alive in the midst of despairing winds of history, as the Sufis taught us.

Such is the complexity of love we diasporics too hold in our hearts for the motherland left behind, a motherland we both despise for what it has become and desire for what it once was.

Tahira Naqvi’s novel is that specially-chiselled diamond that reflects the many contrasting and paradoxical faces of such complicated desire; we must all hold it in our bosoms, reminding us of bygone loves lost, yet in hopes of ever more loves to come. After every winter’s fleurs du mal, there do emerge the flowers of spring.

And for us to ensure that spring never vanishes as promise for our planet’s health, we are directed to one of the novel’s concluding epigraphs by Sartre where he points out: "Life has no meaning a priori…it is up to you to give it a meaning, and value is nothing but the meaning that you choose."

Or as our own beloved Faiz Ahmed Faiz put it:

“Yeh char din kee khudai to koi baat nahin

Hum bhi dekhain ge lazim hai keh hum bhi dekhain ge”

In a way Tahira Naqvi has painted a picture of the Pakistani nakba-the catastrophe all of us of a certain age have witnessed and are continuing to witness because of our worship of false values and our cowardice in speaking up and alongside our society's Others—our deepest Selves.

But just as Palestine one day will be free so too will Pakistan from the neocolonial grip of its own fanatics.

“Dark clouds filled only with lightning and sparks of fire

Are once again looming over the garden,

Surely there will be some light in the darkness

Let us, friends, also light a lamp of our own.”

—Syed Ikram Hussain Ishrat, the author’s father, quoted in The History Teacher of Lahore