“Shaheen” League

Sir,

It was good to hear that the Pakistan Super League (PSL) will be held next year in Doha, Qatar. However, I suggest that the Pakistan Cricket Board rename the PSL the “Pakistan Shaheen League.” The word “Shaheen” adds a resounding Pakistani touch to the name and sets it apart from other cricket leagues.

Mubashir Mahmood,

Karachi.

Integrity for sale

Sir,

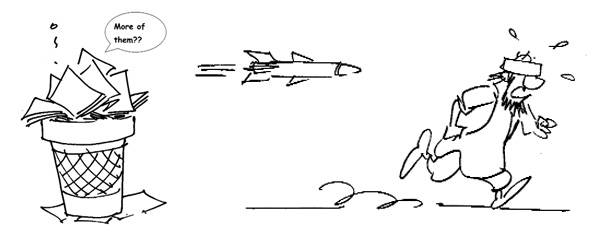

The sacrifices of those who gave their lives to protect the dignity, honour and lives of Pakistan’s citizens should not be allowed to fall prey to the greed of those obsessed with real estate allotments. We owe it to people such as Maj. Aziz Bhatti Shaheed to ensure that the area that now constitutes the Second Defence Line along the BRB Canal remains free of all commercial ventures. At least this would allow our armed forces to move in with their equipment if and when required, with minimal threat to the civilian population.

While the Government of Pakistan must strive for good relations with all our neighbours, there should be no compromise on shoring up our defences. We cannot afford to be caught unawares, given the history of the 1965 war, when India initiated hostilities across internationally recognized borders. Sadly, within India, there remain powerful forces that still harbour ill will towards this country. The events that led up to the 1971 civil war must never be forgotten. If only we had followed Jinnah’s vision of a modern democratic welfare state, Pakistan would have been a far more secure and economically self-reliant sovereign country.

Let us remember that Pakistan was created so that all its institutions – the executive, parliament, judiciary, armed forces and civil bureaucracy – might serve the people and not vice versa. It is, however, the state’s obligation to cater for the welfare of the next of kin of those valiant people who have laid down their lives or been injured in the line of duty. There should be no compromise on national security, nor should greed blind us to the difference between welfare and commercial interests.

Ali Malik Tariq,

Lahore.

Colour-coded

Sir,

This is with reference to the practice among leading political parties of periodically tendering resignations – either to pressurize the government or achieve the party leadership’s motives. I suggest that, in the interests of Pakistan, party members comply with the following stipulations:

1. Tender their resignation on green paper if the act is merely to gain public attention.

2. Use yellow paper if it is to gain public attention, but has some bearing on the concerned person or the state.

3. Use red paper if the resignation is a last resort and will not be reversed under any circumstances. This type of resignation will prove that the person concerned is a person of principle and ready to enter “do or die” mode.

Coloured paper is not the only option – green, yellow or red ink could also be used to achieve the desired objective. It would help make the process more transparent if the resignation was tendered in the presence of the assembly speaker or Senate chairperson – similar to an oath-taking ceremony. This will also discourage the practice of submitting undated resignations to party leaders. Absent members might want to use Skype to call in and confirm their intentions. Unwell members could simply produce a medical board certificate to show they are, indeed, serious about resigning but cannot, regrettably, be there in person. If anything, Pakistan clearly needs a policy governing the process of resignation from the legislative.

Khalid Mustafa,

Islamabad.

Pillion this

Sir,

An analysis of the statistics on crime and terrorism in Karachi reveals that the majority of such heinous acts are committed by people riding motorcycles (which are generally less conspicuous and afford greater mobility and a quicker exit from the scene of the crime). Accordingly, the federal and provincial governments have often enforced a ban on pillion riding and made the use of helmets mandatory for all passengers. In a city that lacks a mass transit system and offers only relatively expensive private transport, this is a kneejerk reaction.

Let us look at some statistics. Currently, there are about 1.75 million motorcycles in Karachi and this number is predicted to increase to over 3.5 million by 2030. Motorcycles offer a cheaper mode of travel and a great deal of flexibility to low-income groups.

How should we address these two diametrically opposed situations? One possible solution (though not without some preliminary effort) would be to make sidecars mandatory for every motorcycle. This would have the advantages of (a) decreasing manoeuvrability and making it harder for criminals and terrorists to blend in on the roads, (b) making it safer for three to four persons to travel together, eventually reducing the number of motorcycle accidents, (c) reducing transport problems, (d) enabling women to ride motorcycles with relative ease and safety, and (e) making it cheaper to travel by motorcycle (currently, it costs a third of what private transport costs).

Agreed, these steps entail certain problems, which can, however, be resolved: (a) congestion on the roads may increase, (b) sidecars represent an additional cost for motorcycle owners, (c) parking problems will likely rise, and (d) the government’s approval will be needed to ply such transport. Given that it is imperative we discourage the use of motorcycles in the hands of terrorists and criminals, while at the same time addressing other constraints, I propose the following: Motorcycles in Karachi should only be allowed with the proviso that they have a sidecar. Those not willing to opt for this should be asked to purchase low-powered electronic motorbikes.

The government should initiate the following additional measures: (a) undertake the necessary changes in the transport rules to allow the use of sidecars with motorcycles, (b) offer sidecars at subsidized rates by entering into agreements with selected manufacturers, (c) standardize the model for safety reasons, (d) reduce the cost by effecting economies of scale and offering sidecars on instalments and microcredit programs, (e) reduce private transport and create separate lanes for motorcyclists, wherever feasible, and (f) reduce duties on motorcycles.

Shahriyar Nawaz Haq,

Karachi.

Men at work

Sir,

“You will be proud to know I have brought in PRs 100 billion to Pakistan without any assistance from the government,” the DG of the Frontier Works Organization (FWO) said to us. His sense of pride was visible, not for himself, but for Pakistan. The university students sitting in the conference room realized that it was not just the roads the FWO builds, but also the organization’s spirit that contributes to building Pakistan.

This is how every individual can prove to be important in nation building. Meeting the engineers stationed at a construction site near the Panead River in the scorching heat made us realize just how committed they were to their work. I could never have thought that building roads might be motivational, but for this group of workers, it certainly seemed to be. Even the risk of accidents and death while working in hazardous terrain did not leave them discouraged. Hats off to the FWO for the work they do.

Mahrukh Sarfraz,

Rawalpindi.

Carry on, doctor

Sir,

“You are going to be a doctor.” A statement that has pushed many people into a dilemma, compelling them to pursue a career that is, practically speaking, not possible for everyone – not because they are any less capable, but because the situation can be manipulated to generate money. Every year, thousands of students across the country apply to medical school and are required to sit an entrance test. The test effectively nullifies their four years of college education and requires them to prove their eligibility for entrance in two short hours.

Are four years of examinations not enough? Must students be put through yet another test? A test in which the enormous number of applications received creates massive scope for revenue? The minimum criterion for a successful application is 60 percent. Students who have been unable to reach this target in their four years of college have to compete with those able to pull off 90 percent. This minimum criterion simply gives the academy preparation system a chance to exploit students desperate to get into medical school and prepared to find any way of doing so.

Above all, there are simply not enough medical colleges in Pakistan, thus fuelling the competition and leaving unsuccessful students discouraged, their careers having been brought to a halt before even taking off. Doctors are in demand, certainly, but the institutions needed to produce this workforce do not reflect the demand for healthcare services. The sector faces a lack of scenario planning: only a well-planned and well-implemented system will ensure that talented students are not lost for the wrong reasons. There is no point having an entry test for any institution unless the circumstances deliberately created to exploit this are stopped.

Namra Naseer,

Rawalpindi.

Fallen, not defeated

Sir,

“Never think we are weak or feeble. Never think you can hide from us or breathe in peace: we will target you even from the depths of the Arabian Sea or the highest mountain.” This message, relayed to the terrorists that continue to plague Pakistan, left me feeling grave, but moved. These are the words of Maj. Qasim, who was part of the Pakistan Army’s operations in Orakzai Agency. He is nothing short of a living miracle here at the Armed Forces Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine (AFIRM) and, indeed, the epitome of courage.

Maj. Qasim suffered head and upper limb injuries during the operation in Orakzai. “I am here to get well. I have to go back as soon as possible and play my part in bringing peace to the country for you and for the generations to come,” he said to me vigorously. He has been at AFIRM for a whole year now. His doctors say that, when he first came to them, he had lost his vision, speech and mobility as a result of the severe injuries he had sustained. With the help of occupational, vocational and other therapies here at AFIRM – and, of course, his own determination and unabashed optimism – Maj. Qasim is now gradually recovering.

This is not the only case of its kind. AFIRM has dealt unremittingly with many such cases and remains committed to providing health services to the people who need them most. Initially, as I walked through its halls, involved in my research, I thought it to be like any other hospital. But AFIRM is much more than that: its patient–doctor relationships, high-quality treatment and well-maintained departments set it apart. AFIRM was established in 1980 and has been upgraded over the years. It serves not only the armed forces, but also civilians, for instance, people with physical disabilities or accident and trauma victims. The best example of this is the role it played just after the 2005 earthquake in northern Pakistan, where the sheer number of casualties proved a seemingly insurmountable challenge. AFIRM provided a large number of earthquake-affected people complete treatment, including physical therapy, amputations and prosthetic limbs.

“I have only lost a leg, not my spirits!” There is a kind of glee in Sepoy Noorshad Ali’s voice as he puts on his prosthetic running blade (sports leg) instead of his prosthetic lower limb. Ali, also a keen sportsman, lost his leg in an LED blast in Mohmand Agency during the counter-terrorist operation there. The running blade furnished by AFIRM is a special prosthetic device, which allows him to continue playing sports despite his injury.

Sepoy Usama Ashraf was admitted to AFIRM two months ago, having lost a leg in a mine blast in Mohmand Agency during Operation Zarb-e-Meezan. All that is left is a heavily bandaged stump just below his knee. But his eyes mist over as he says how grateful he is to the army, to AFIRM and to his comrades. “Even now, two months down the line,” he says, “I still receive a call every day from my friends and unit officers, wishing me health and prosperity.”

I remain astonished by their unfazed spirit and determination. Even a quadratic amputee (one who had lost both his upper and lower limbs) I met at AFIRM was full of hope. I realize now that the only battle we need to win is the battle within.

Areesha Latif,

Lahore.