I“Chillis have been born in every era and every class….We are all Chillis.”

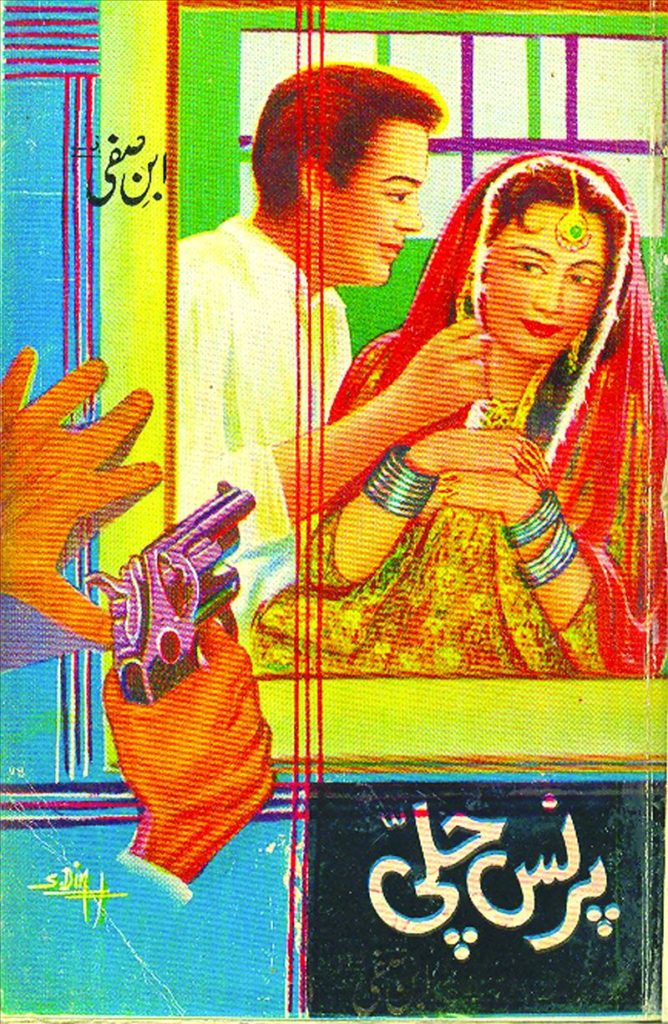

was least prepared by this candid disclaimer given in the author’s preface to the astonishing novel titled Prince Chilli by Ibne Safi, the great pioneer of detective novels in Urdu, who passed away 40 years ago this past July in Karachi. Astonishing, because while this novel can be read as a relatively enjoyable romp of romance and intrigue, it deserves to be much better known as a social satire chronicling the social and cultural background of Pakistan in the 1950s and 1970s.

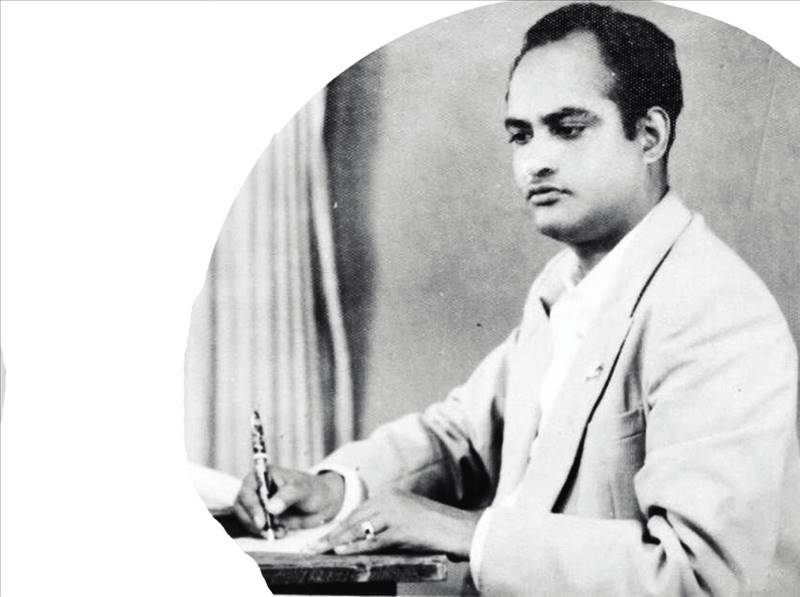

Ibne Safi carved a universal reputation for himself and the genre of detective fiction in Urdu across the Subcontinental divide over his relatively short life. However, merely to define him as a writer of pulp potboilers does no justice to his considerable talent, for he was also a poet and satirist of no mean accomplishment. This is the sense I got from Safi’s son when I met him in Lahore two years ago, one month into the monsoon season, in the first week of August. 2018 was, after all, the 90th birthday year of Ibne Safi. I had resolved to write something on his work at that time, but then instinctively abandoned the project and moved on to other things.

At the outset, one must understand and appreciate that the tradition of a social or political satirical novel in Urdu is not very old. That is not to say that there was never any satire in Urdu fiction. If we are to take Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor’s word for it, then the first-ever Urdu social- satirical novel was Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s dystopian Bees Sau Gayara (Twenty Hundred and Eleven) which celebrates its 70th publication anniversary in September this year. This information makes Safi’s effort under review only the second Urdu novel intended as a purely social-political satire. Both novels were originally written in the 1950s and both have been neglected by readers and critics alike, perhaps being overshadowed by their creators’ more illustrious careers in humour and detective stories respectively.

Unlike Akhtar’s novel, Safi’s Prince Chilli has a very interesting publication history, which enables the reader to put the novel in the perspective of two important periods in Pakistan’s political history. In the preface to the novel, Safi informs us that he originally wrote the first part of the novel in 1958 titled Zulfen Pareshan Ho Gayeen (The Tresses Became Scattered), while the second part together with the first was published in its present form in 1977, after almost two decades. The date on the expanded edition is November 1, 1977. Both the years are significant; 1958 was the year when Pakistan’s first military dictatorship under Ayub Khan came to power, while the country’s first democratically elected prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was overthrown in July 1977 by Pakistan’s third military ruler General Zia-ul-Haq. Given this background, the novel is basically a story of those powerful groups which are spread throughout the country in the form of student unions. Politicians, bureaucrats, police and influential people use these student organizations for their respective objectives. Consequently, many students become inclined towards student politics and their influence and importance also increases greatly. Along with the student organizations, this story also unveils greed and family fights. Chilli is actually not the name of an individual, but a condition which can overcome anybody. Safi writes about this himself in the aforementioned preface to the novel, which is itself a model of his mood and his mastery of humour:

“The history of Chilli is perhaps as old as that of evolution. Chillis have been born in every era and every class. From Prince Chilli to Sheikh Chilli; from the Stone Age to the Space Age, one will see an abundance of Chillis. He even dreams of ruling the Heavens by establishing himself upon the throne of empire, and as Sheikh Chilli, starting with the egg, even washes his hands with the pot of ghee. Whatever the case, he indeed provides a source of entertainment for the ‘non-Chillis’, whether he falls upon his head alongwith the throne from the sky to the earth like Afrasiab owing to the treachery of the hawks, or whether he makes the pot of ghee fall off his head while scolding his imaginary children.

Had there been no Chillis, human history would have been totally blank. There would have been neither wars nor the flourishing of the rule of prostitutes. There would have been neither rise nor fall. The world would not have been so bright at all and various types of Chillis would not have put their lives at stake for it.

Chilli is a standard; a measure. Analyze the whole life of the wisest person keeping in mind his end and then do think placing a finger to your chin, ‘Yar he too was a Chilli.’

‘Chillism’ is a universal reality. We are all Chillis. But it is very odd that separating ourselves from this crowd, we remain in search of other Chillis for entertainment. If you don’t believe me, then just have a look at your castles in the air, and if the hawks tied round the feet of the throne do not deceive you, then I will be responsible. If the pot of ghee does not fall off the head, I will be answerable. Meaning that, ‘I am Chilli, you are Chilli, indeed the whole world is Chilli’”

The late 1950s – the period when the novel was written – was a problematic period for Pakistan’s history. It was not a halcyon time to be a student. Pakistani colleges faced immense social and cultural problems. Even before the anti-labor, anti-student coup of 1958, Pakistani students faced issues of rising tuition fees, inadequate or nonexistent library facilities, better classes and the establishment of a proper university, for the fulfillment of which the leftist Democratic Students Federation (DSF) came into being in 1953. The government responded by founding a parallel organization called the National Students Federation (NSF), consisting of the old nationalist student wing of the All India Muslim League, the Muslim Students Federation (MSF) and conservative students to counter these demands. Indeed in the novel itself, the main protagonist Raees-ul-Hasan is shown to be enrolled in the second year of college for the past 8 years. Both students and professors were wary of him; he was a day scholar but chose to remain in the student hostel. Then there were social problems like gambling through cards prevalent on campus and ignored by the warden to preserve his own privileges. Here it may also be mentioned that a very poignant symbol of the clash of the old versus the new is that Prince Chilli is willing to shave off his beard in return for being patronized by his newfound ‘Chacha’ Raees. This patronization comes into effect when Chilli’s father disinherits him after learning of the latter’s shaving off his beard, since the Prince cannot pay his tuition fee and mess charges any more; Raees has access to a fund he has set up for the Association for Raising the Children of Incompetent Parents! n

(to be continued)

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

was least prepared by this candid disclaimer given in the author’s preface to the astonishing novel titled Prince Chilli by Ibne Safi, the great pioneer of detective novels in Urdu, who passed away 40 years ago this past July in Karachi. Astonishing, because while this novel can be read as a relatively enjoyable romp of romance and intrigue, it deserves to be much better known as a social satire chronicling the social and cultural background of Pakistan in the 1950s and 1970s.

Ibne Safi carved a universal reputation for himself and the genre of detective fiction in Urdu across the Subcontinental divide over his relatively short life. However, merely to define him as a writer of pulp potboilers does no justice to his considerable talent, for he was also a poet and satirist of no mean accomplishment. This is the sense I got from Safi’s son when I met him in Lahore two years ago, one month into the monsoon season, in the first week of August. 2018 was, after all, the 90th birthday year of Ibne Safi. I had resolved to write something on his work at that time, but then instinctively abandoned the project and moved on to other things.

At the outset, one must understand and appreciate that the tradition of a social or political satirical novel in Urdu is not very old. That is not to say that there was never any satire in Urdu fiction. If we are to take Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor’s word for it, then the first-ever Urdu social- satirical novel was Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s dystopian Bees Sau Gayara (Twenty Hundred and Eleven) which celebrates its 70th publication anniversary in September this year. This information makes Safi’s effort under review only the second Urdu novel intended as a purely social-political satire. Both novels were originally written in the 1950s and both have been neglected by readers and critics alike, perhaps being overshadowed by their creators’ more illustrious careers in humour and detective stories respectively.

Unlike Akhtar’s novel, Safi’s Prince Chilli has a very interesting publication history, which enables the reader to put the novel in the perspective of two important periods in Pakistan’s political history. In the preface to the novel, Safi informs us that he originally wrote the first part of the novel in 1958 titled Zulfen Pareshan Ho Gayeen (The Tresses Became Scattered), while the second part together with the first was published in its present form in 1977, after almost two decades. The date on the expanded edition is November 1, 1977. Both the years are significant; 1958 was the year when Pakistan’s first military dictatorship under Ayub Khan came to power, while the country’s first democratically elected prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was overthrown in July 1977 by Pakistan’s third military ruler General Zia-ul-Haq. Given this background, the novel is basically a story of those powerful groups which are spread throughout the country in the form of student unions. Politicians, bureaucrats, police and influential people use these student organizations for their respective objectives. Consequently, many students become inclined towards student politics and their influence and importance also increases greatly. Along with the student organizations, this story also unveils greed and family fights. Chilli is actually not the name of an individual, but a condition which can overcome anybody. Safi writes about this himself in the aforementioned preface to the novel, which is itself a model of his mood and his mastery of humour:

Ibne Safi carved a universal reputation for himself and the genre of detective fiction in Urdu across the Subcontinental divide over his relatively short life

“The history of Chilli is perhaps as old as that of evolution. Chillis have been born in every era and every class. From Prince Chilli to Sheikh Chilli; from the Stone Age to the Space Age, one will see an abundance of Chillis. He even dreams of ruling the Heavens by establishing himself upon the throne of empire, and as Sheikh Chilli, starting with the egg, even washes his hands with the pot of ghee. Whatever the case, he indeed provides a source of entertainment for the ‘non-Chillis’, whether he falls upon his head alongwith the throne from the sky to the earth like Afrasiab owing to the treachery of the hawks, or whether he makes the pot of ghee fall off his head while scolding his imaginary children.

Had there been no Chillis, human history would have been totally blank. There would have been neither wars nor the flourishing of the rule of prostitutes. There would have been neither rise nor fall. The world would not have been so bright at all and various types of Chillis would not have put their lives at stake for it.

Chilli is a standard; a measure. Analyze the whole life of the wisest person keeping in mind his end and then do think placing a finger to your chin, ‘Yar he too was a Chilli.’

‘Chillism’ is a universal reality. We are all Chillis. But it is very odd that separating ourselves from this crowd, we remain in search of other Chillis for entertainment. If you don’t believe me, then just have a look at your castles in the air, and if the hawks tied round the feet of the throne do not deceive you, then I will be responsible. If the pot of ghee does not fall off the head, I will be answerable. Meaning that, ‘I am Chilli, you are Chilli, indeed the whole world is Chilli’”

The late 1950s – the period when the novel was written – was a problematic period for Pakistan’s history. It was not a halcyon time to be a student. Pakistani colleges faced immense social and cultural problems. Even before the anti-labor, anti-student coup of 1958, Pakistani students faced issues of rising tuition fees, inadequate or nonexistent library facilities, better classes and the establishment of a proper university, for the fulfillment of which the leftist Democratic Students Federation (DSF) came into being in 1953. The government responded by founding a parallel organization called the National Students Federation (NSF), consisting of the old nationalist student wing of the All India Muslim League, the Muslim Students Federation (MSF) and conservative students to counter these demands. Indeed in the novel itself, the main protagonist Raees-ul-Hasan is shown to be enrolled in the second year of college for the past 8 years. Both students and professors were wary of him; he was a day scholar but chose to remain in the student hostel. Then there were social problems like gambling through cards prevalent on campus and ignored by the warden to preserve his own privileges. Here it may also be mentioned that a very poignant symbol of the clash of the old versus the new is that Prince Chilli is willing to shave off his beard in return for being patronized by his newfound ‘Chacha’ Raees. This patronization comes into effect when Chilli’s father disinherits him after learning of the latter’s shaving off his beard, since the Prince cannot pay his tuition fee and mess charges any more; Raees has access to a fund he has set up for the Association for Raising the Children of Incompetent Parents! n

(to be continued)

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com