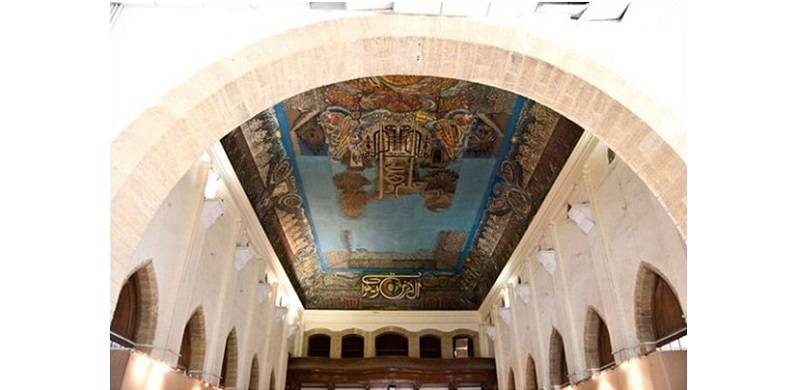

Standing in the large galleries of Pakistan National College of the Arts (PNCA) in Islamabad today. Looking at the iconic paintings of Sadequain. Mesmerised still, trying to decipher some said and some unsaid codes. The necromantic Cacti with never-ending resilience. The glaring Sun, black, gray. Haunting red, orange contrasts and magic painted by those crooked fingers which were twisted because passion has no limit.

I become small! Smaller than when I was first introduced to Sadequain's illustrious work. Two pigtails, grey blue dress with maroon collar and belt, hands holding each other at the back, large black eyes which opened wider and bigger like those painted by Margaret D.H. Keane (born Peggy Doris Hawkins, 15 September 1927), standing in awe of the paintings hanging in Mrs. Hamids' Hall and Library of PECHS Girls’ School and College (now BAMM School) in Karachi. Looking at the paintings, wondering about those Greek faces (Sadequain's self-portrayal), unending fingers and toes, eyes dark and whispering, hidden yet present visible insinuations of "I am...you are...". Meanings too meaningful for a young child to comprehend. And yet awe inspiring: then and now!

Reminiscing about the artful days. Laying on the floor of Frere Hall Karachi, absorbing murals by the giant of art in stature, who was rather frail and modiqué physically. Putting the puzzles together of calligraphic illustrations, falling into the timelessness of space is still true narration of Sadequain's labour of love.

Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, born in Amroha (British India), was quite proud of being Najeeb-ul-Tarfain, where calligraphy was his inheritance. Full of sentiments this young man joined in the late 1940s the Progressive Writers’ and Artists’ Movement.

Sadequain was an integral part of a broader movement which emerged independently from North Africa and parts of Asia known as Hurrufiya movement in calligraphy. The Hurrufiya movement rejected Western art concepts. This calligraphic form combined traditional art forms, notably calligraphy, as a graphic element within contemporary artwork. Sadequain was the Master of this movement, who searched for new visual languages and translated his own culture and traditional heritage. He transformed calligraphy into a modern aesthetic, which was both contemporary and indigenous. Sadequain became the pioneer of bringing calligraphy into the mainstream art forms and influenced subsequent generations of Pakistani artists.

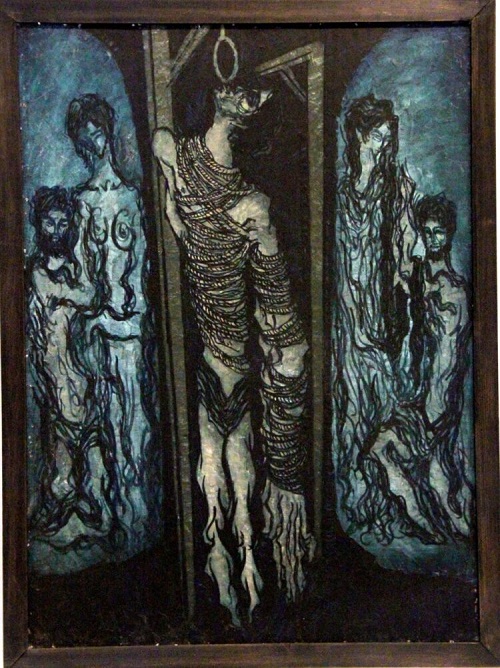

His school of thought believed in enriching realism with lyricism. Like Picasso, Sadequain worked in linear forms. He skillfully experimented with realist pen and ink endeavours, and a decade later moved to Paris in the 1960s, where he invented ground-breaking fresh forms of calligraphic cubism.

He sometimes used Kufic script to form human images and carried that theme through vast canvases. One of the representative works of this genre is titled "The Last Supper."

He sometimes used Kufic script to form human images and carried that theme through vast canvases. One of the representative works of this genre is titled "The Last Supper."

The decade of the 1960s represents the most explosive period of Sadequain’s artistic genius, when he defined new idioms and developed his unique iconography while living in Paris, France. He invented new artistic forms, which, it can be argued, had not been explored before. Yet, this phase of Sadequain’s odyssey remains most elusive, because most of his work from this era remains in the attics of Parisian homes and art galleries.

Sadequain, the Michelangelo of Pakistan, painted numerous murals of allegorical proportions, which none to this date can claim to have worked on.

"Though this be madness, yet there is method in't"

Hamlet seems to have said this for Sadequain. His passion drove him, ruled him. He worked day and night, not much bothered about food and rest.

We know Sadequain as the master of calligraphic illustrations, interpreting the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Mirza Ghalib and Allama Iqbal through his calligraphic illustrations. He translated the work of Albert Camus into illustrations. What we don't much talk about is his poetic skill. Sadequain composed flawless, rhythmic, true-to-his-nature Rubaiyat (prosodic quatrain). His subject was merely Life...

What could be a more natural form of expression?

Art is also a chronicle and interpretation of the life of an artist...

Being a creator of this magnitude, he soared high, never scared of getting his wings burned by norms. He had the fire of a rebel, which made him care less about being widely accepted by the kind who go with the flow.

He retained his beliefs and lived by them. And so, he wasn't commercial: he would not care to sell his art, only to decorate the drawing rooms of the rich. He produced public good by painting murals, depicting the dignity of human labour, donating most of his work to the public sector.

Sadequain deeply cared for society, and especially the youth. He commented on the good and bad. He urged youth specifically to explore their potential and expose it.

There is never the right time to celebrate our heroes. An artist of such gigantic proportions needs no reason to be remembered.

Such masters are with us always: mentoring our quests for art and literature.

I become small! Smaller than when I was first introduced to Sadequain's illustrious work. Two pigtails, grey blue dress with maroon collar and belt, hands holding each other at the back, large black eyes which opened wider and bigger like those painted by Margaret D.H. Keane (born Peggy Doris Hawkins, 15 September 1927), standing in awe of the paintings hanging in Mrs. Hamids' Hall and Library of PECHS Girls’ School and College (now BAMM School) in Karachi. Looking at the paintings, wondering about those Greek faces (Sadequain's self-portrayal), unending fingers and toes, eyes dark and whispering, hidden yet present visible insinuations of "I am...you are...". Meanings too meaningful for a young child to comprehend. And yet awe inspiring: then and now!

Reminiscing about the artful days. Laying on the floor of Frere Hall Karachi, absorbing murals by the giant of art in stature, who was rather frail and modiqué physically. Putting the puzzles together of calligraphic illustrations, falling into the timelessness of space is still true narration of Sadequain's labour of love.

Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, born in Amroha (British India), was quite proud of being Najeeb-ul-Tarfain, where calligraphy was his inheritance. Full of sentiments this young man joined in the late 1940s the Progressive Writers’ and Artists’ Movement.

Sadequain was an integral part of a broader movement which emerged independently from North Africa and parts of Asia known as Hurrufiya movement in calligraphy. The Hurrufiya movement rejected Western art concepts. This calligraphic form combined traditional art forms, notably calligraphy, as a graphic element within contemporary artwork. Sadequain was the Master of this movement, who searched for new visual languages and translated his own culture and traditional heritage. He transformed calligraphy into a modern aesthetic, which was both contemporary and indigenous. Sadequain became the pioneer of bringing calligraphy into the mainstream art forms and influenced subsequent generations of Pakistani artists.

His school of thought believed in enriching realism with lyricism. Like Picasso, Sadequain worked in linear forms. He skillfully experimented with realist pen and ink endeavours, and a decade later moved to Paris in the 1960s, where he invented ground-breaking fresh forms of calligraphic cubism.

He sometimes used Kufic script to form human images and carried that theme through vast canvases. One of the representative works of this genre is titled "The Last Supper."

He sometimes used Kufic script to form human images and carried that theme through vast canvases. One of the representative works of this genre is titled "The Last Supper."The decade of the 1960s represents the most explosive period of Sadequain’s artistic genius, when he defined new idioms and developed his unique iconography while living in Paris, France. He invented new artistic forms, which, it can be argued, had not been explored before. Yet, this phase of Sadequain’s odyssey remains most elusive, because most of his work from this era remains in the attics of Parisian homes and art galleries.

Sadequain, the Michelangelo of Pakistan, painted numerous murals of allegorical proportions, which none to this date can claim to have worked on.

"Though this be madness, yet there is method in't"

Hamlet seems to have said this for Sadequain. His passion drove him, ruled him. He worked day and night, not much bothered about food and rest.

We know Sadequain as the master of calligraphic illustrations, interpreting the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Mirza Ghalib and Allama Iqbal through his calligraphic illustrations. He translated the work of Albert Camus into illustrations. What we don't much talk about is his poetic skill. Sadequain composed flawless, rhythmic, true-to-his-nature Rubaiyat (prosodic quatrain). His subject was merely Life...

ﮔﮭر ﭘر وه ﭘﮑﺎ ﮐﮯ آﻟو ﭘﺎﻟﮏ آﺋﯽ

ﺑﺎرش ﻣﯾں ﺑﮭﯽ وه ﻣﻧزل و ﻓﺎﺗﮏ آﺋﯽ

ﻟﮯ ﺗو ﻧہ ﺗﮭﺎ اور ﮐل وه ﺧﻼف اﻣﯾد

ﺳﺎدھو ﮐﮯ ﺷواﻟﮯ ﻣﯾں اﭼﺎ ﻧﮏ آﺋﯽ

What could be a more natural form of expression?

Art is also a chronicle and interpretation of the life of an artist...

ﻏﺎﻟب و ﻣﺎرﮐس

ﻧظر ﺑﺎر ﯾﮏ ﺗﻧﯽ ﺑﮯ ﺳد ﺣﮑﯾم اﻗﺗﺻﺎدی ﮐﯽ ﺧرد ﺗﮭﯽ ﺗﯾز ﻟﯾﮑن ﮐس ﻗدر اﺳﺗﺎدﺣﺎﻟﯽ ﮐﯽ ﯾہ دو ﮨم ﻋﺻر ﺗﮭﮯ ﺟن ﮐﺎ ﺗﺧﯾل ﺗﻘﺎﺑﻠﻧدی ﭘر اﻧﮩﯾں ﮐﺎ ﻗول ﮨﮯ ﺗﺻوﯾر ﮐﯽ زﻧدﮔﺎﻧﯽ ﮐﯽ ﮐوﺋﯽ ﻣﺎﺣول ﺟب ﮨوﺗﺎ ﮨﮯ ﻗﺎﺋم ﺧود ﯾہ ﮐﮩﺗﺎﮨﯽ ﻣری ﺗﻌﻣﯾہ ﻣﯾں ﻣﺿﻣر ﮨﮯ اک ﺻورت ﺧراﺑﯽ ﮐﯽ ﮨوﺋﯽ ﺑرق ﻓرﺳن ﮐﺎ ﮨﮯ ﺗون ﮔرم وﮨﺎں ﮐﺎ

Being a creator of this magnitude, he soared high, never scared of getting his wings burned by norms. He had the fire of a rebel, which made him care less about being widely accepted by the kind who go with the flow.

He retained his beliefs and lived by them. And so, he wasn't commercial: he would not care to sell his art, only to decorate the drawing rooms of the rich. He produced public good by painting murals, depicting the dignity of human labour, donating most of his work to the public sector.

Sadequain deeply cared for society, and especially the youth. He commented on the good and bad. He urged youth specifically to explore their potential and expose it.

There is never the right time to celebrate our heroes. An artist of such gigantic proportions needs no reason to be remembered.

Such masters are with us always: mentoring our quests for art and literature.