“Please forgive me. My illness won today. Please look after each other, the animals, and global poor for me. All my love.”

These heart-wrenching words were written by 25-year-old Tommy, the only son of the prominent US Congressman from Maryland, a former professor of constitution law, Jamie Raskin. It was the last communication from Tommy to his family before he ended his life. The loss of a child is said to be the single most devastating event from which a parent never fully recovers.

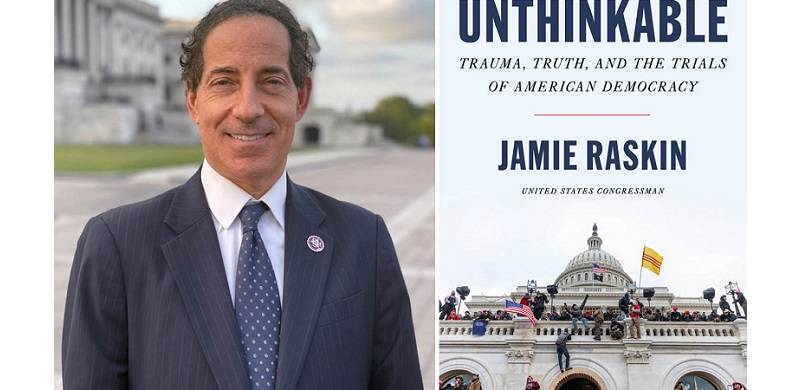

A brilliant law student at Harvard University, Tommy Raskin had long suffered from debilitating bouts of anxiety and depression that could not be controlled even by the best available medical treatments. Mental illness often afflicts the young, mostly men, and progressively gets worse. In his highly acclaimed book, Unthinkable (HarperCollins), Raskin, the father, describes in painful detail how his son increasingly descended into the abyss of despair. Tommy had a normal, happy childhood, loved to tell jokes, laugh, and play pranks on others.

While growing up, he was a compassionate young man, opposed all conflicts and was especially sensitive to cruelty to animals. As a high school student, he spent inordinate amounts of time tutoring other fellow students who needed help in mathematics and English, became a vegan, abjured eating all meat products. The bloodshed in Yemen, like all wars, distressed him. Born in a Jewish family, he strongly advocated justice for Palestinians and dreamed about winning the Nobel Peace Prize for resolution of the Middle East conflict.

Some early signs of trouble, however, appeared on the horizon when Tommy was a teenager. These were dismissed by his parents as just eccentric behavior on his part. Unlike most teenagers, who are anxious to learn and drive a car, Tommy was not keen on driving. He went as far as to obtain a learner’s permit, but never applied for a proper license. He worried that if he drove, he might hurt some person or animal. His parents could not disabuse him from this unreasonable concern.

Similarly, as a student at the prestigious Amherst College in Massachusetts, he worried excessively about hurting his friends’ feelings, and even obsessed about events that happened years ago. Otherwise, he was a bright student who was doing well in his studies and was able to make friends. Many teenagers go through phases when they feel down and depressed, but in time regain their equilibrium, so his behavior was not considered abnormal. To address mental health problems, many schools employ mental health experts and counselors with whom students can have frank, open conversations.

In his second year of college, it was becoming clear that all was not well with the seemingly bright student. There is a long-held stigma associated with mental illness and patients often suffer in silence, preferring never to reveal their personal agony and private hell they live in. Tommy also never wanted to share his pain or talk about his mental anguish—even to his parents, his two sisters or close friends. His parents noticed that he was not sleeping well when at home, and when he did so, he had vivid, frightening nightmares. The sleep problem was treated with the usual sleeping pills but brought only temporary relief. Ultimately, his parents got some inkling of the severity of the problem and sought professional help. The psychiatrist diagnosed depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, ailments that are treatable or at least controllable.

Later, at Harvard Law School, Tommy seems to have regained his self-assurance. Working as an intern and teaching assistant, he spent hours tutoring and guiding his undergraduate students. But, ultimately, two developments seemingly upended his fragile mental peace. First was the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic and the misery and toll of life it inflicted world-wide. Secondly, the extreme right-wing policies of the newly elected US president, Donald Trump. In the face of these problems, Tommy felt helpless. He was a regular blood donor and, as the pandemic took hold, he started showing up for blood donations more frequently than before, even risking his health.

Occasionally, Tommy allowed his anxious parents to peek into the inner sanctums of his mind. Raskin mentions that, in one conversation, his son ruefully remarked that he never expected to be happy. The comment out of nowhere alarmed his father. Raskin attempted to talk him out of the despondency, quoting Freud’s explication that happiness really means being with friends, family, eating well and working. The sage advice had little effect.

A few weeks before the end, a mysterious aura of serenity and tranquility swaddled Tommy as if he had finally found peace; his mind having made a decision was now at rest. The most touching section of the book is the description by the author of the last day he spent with his son. In hindsight, there were subtle indications in his actions that he was saying goodbye. He wrote long notes to all his students providing some excellent guidance, made very generous gifts to charities he cherished. 30 December 2020 was the last day of his life. The father and son shared the evening meal, and nothing seemed abnormal or out of place The father, always worried, asked Tommy how he was doing, He responded with just one word “Good.” Except for the desultory answer, there was nothing amiss.

Since Tommy was planning to be out on the following evening, he asked the father whether he would be alright alone on New Year’s Eve. Then, he politely declined the offer to watch a movie; he was tired, he said, and wanted to retire early. “He got up and I gave him a big hug; ‘Love you, dear boy,’ I said. ‘Love you, dear Dad,’ he replied. And that was the last time I saw my son alive.”

The author has not shared the heartbreaking details of how he discovered the lifeless body of his son in the morning in his bed. Tommy left the goodbye note reproduced in the opening paragraph of this article. Raskin describes how many times over many sleepless nights he agonised whether there was anything he could have done to save his son’s life, perhaps, not leaving him alone, perhaps a frank talk on whether he was contemplating suicide. The possibilities are endless, but no clear answers. The book offers invaluable insights into the emotional agony of a parent and documents a father’s remarkable tribute to his son’s memory. The portrayal will resonate with many parents experiencing similar pain.

These heart-wrenching words were written by 25-year-old Tommy, the only son of the prominent US Congressman from Maryland, a former professor of constitution law, Jamie Raskin. It was the last communication from Tommy to his family before he ended his life. The loss of a child is said to be the single most devastating event from which a parent never fully recovers.

A brilliant law student at Harvard University, Tommy Raskin had long suffered from debilitating bouts of anxiety and depression that could not be controlled even by the best available medical treatments. Mental illness often afflicts the young, mostly men, and progressively gets worse. In his highly acclaimed book, Unthinkable (HarperCollins), Raskin, the father, describes in painful detail how his son increasingly descended into the abyss of despair. Tommy had a normal, happy childhood, loved to tell jokes, laugh, and play pranks on others.

While growing up, he was a compassionate young man, opposed all conflicts and was especially sensitive to cruelty to animals. As a high school student, he spent inordinate amounts of time tutoring other fellow students who needed help in mathematics and English, became a vegan, abjured eating all meat products. The bloodshed in Yemen, like all wars, distressed him. Born in a Jewish family, he strongly advocated justice for Palestinians and dreamed about winning the Nobel Peace Prize for resolution of the Middle East conflict.

Some early signs of trouble, however, appeared on the horizon when Tommy was a teenager. These were dismissed by his parents as just eccentric behavior on his part. Unlike most teenagers, who are anxious to learn and drive a car, Tommy was not keen on driving. He went as far as to obtain a learner’s permit, but never applied for a proper license. He worried that if he drove, he might hurt some person or animal. His parents could not disabuse him from this unreasonable concern.

Similarly, as a student at the prestigious Amherst College in Massachusetts, he worried excessively about hurting his friends’ feelings, and even obsessed about events that happened years ago. Otherwise, he was a bright student who was doing well in his studies and was able to make friends. Many teenagers go through phases when they feel down and depressed, but in time regain their equilibrium, so his behavior was not considered abnormal. To address mental health problems, many schools employ mental health experts and counselors with whom students can have frank, open conversations.

In his second year of college, it was becoming clear that all was not well with the seemingly bright student. There is a long-held stigma associated with mental illness and patients often suffer in silence, preferring never to reveal their personal agony and private hell they live in. Tommy also never wanted to share his pain or talk about his mental anguish—even to his parents, his two sisters or close friends. His parents noticed that he was not sleeping well when at home, and when he did so, he had vivid, frightening nightmares. The sleep problem was treated with the usual sleeping pills but brought only temporary relief. Ultimately, his parents got some inkling of the severity of the problem and sought professional help. The psychiatrist diagnosed depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, ailments that are treatable or at least controllable.

Later, at Harvard Law School, Tommy seems to have regained his self-assurance. Working as an intern and teaching assistant, he spent hours tutoring and guiding his undergraduate students. But, ultimately, two developments seemingly upended his fragile mental peace. First was the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic and the misery and toll of life it inflicted world-wide. Secondly, the extreme right-wing policies of the newly elected US president, Donald Trump. In the face of these problems, Tommy felt helpless. He was a regular blood donor and, as the pandemic took hold, he started showing up for blood donations more frequently than before, even risking his health.

Occasionally, Tommy allowed his anxious parents to peek into the inner sanctums of his mind. Raskin mentions that, in one conversation, his son ruefully remarked that he never expected to be happy. The comment out of nowhere alarmed his father. Raskin attempted to talk him out of the despondency, quoting Freud’s explication that happiness really means being with friends, family, eating well and working. The sage advice had little effect.

A few weeks before the end, a mysterious aura of serenity and tranquility swaddled Tommy as if he had finally found peace; his mind having made a decision was now at rest. The most touching section of the book is the description by the author of the last day he spent with his son. In hindsight, there were subtle indications in his actions that he was saying goodbye. He wrote long notes to all his students providing some excellent guidance, made very generous gifts to charities he cherished. 30 December 2020 was the last day of his life. The father and son shared the evening meal, and nothing seemed abnormal or out of place The father, always worried, asked Tommy how he was doing, He responded with just one word “Good.” Except for the desultory answer, there was nothing amiss.

Since Tommy was planning to be out on the following evening, he asked the father whether he would be alright alone on New Year’s Eve. Then, he politely declined the offer to watch a movie; he was tired, he said, and wanted to retire early. “He got up and I gave him a big hug; ‘Love you, dear boy,’ I said. ‘Love you, dear Dad,’ he replied. And that was the last time I saw my son alive.”

The author has not shared the heartbreaking details of how he discovered the lifeless body of his son in the morning in his bed. Tommy left the goodbye note reproduced in the opening paragraph of this article. Raskin describes how many times over many sleepless nights he agonised whether there was anything he could have done to save his son’s life, perhaps, not leaving him alone, perhaps a frank talk on whether he was contemplating suicide. The possibilities are endless, but no clear answers. The book offers invaluable insights into the emotional agony of a parent and documents a father’s remarkable tribute to his son’s memory. The portrayal will resonate with many parents experiencing similar pain.