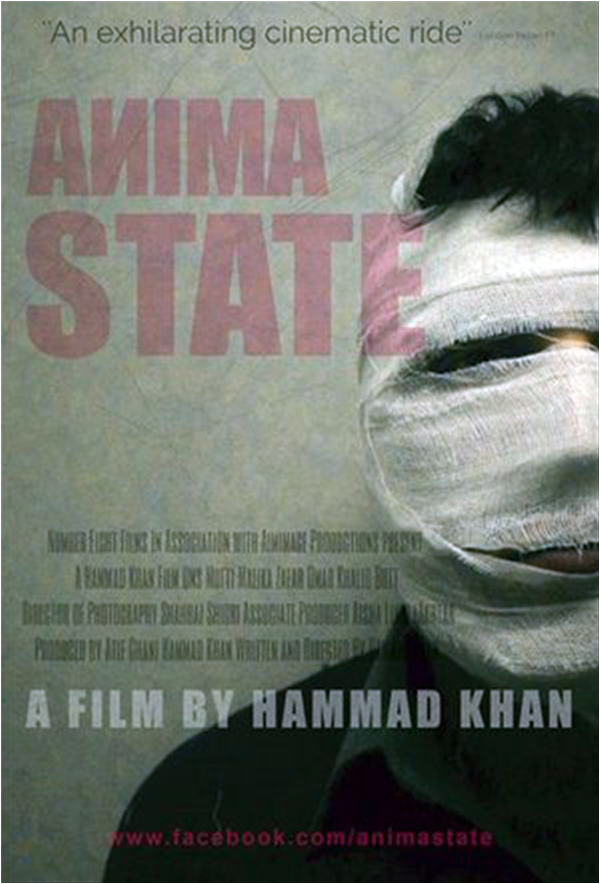

Director Hammad Khan opens Anima State with the following explanation:

“Anima: The part of the psyche that is directed inward and in touch with the subconscious

State: Condition, situation or country.”

In a tranquil scene of an outdoor cafe the opening scene of the murder of five is as mundane as the daily violence that plagues this country. The difference, however, is that these are targets who are usually safe from much randomness. Their blood-speckled belongings – smart phones, shades, a designer bag and foreign clothing – reveal their backgrounds: the Elite of Pakistan, hated by some simply for what they are born with, and on occasion, because of what they do with that privilege.

Interestingly the young group that gets shot are also the stars of Slackistan, the director Hammad Khan’s first film that received mixed reviews, a ban in Pakistan and some ire for its focus on the country’s slackers. Later in the film “the tweeter” meets the central character, resulting in him getting beaten up by these Keyboard Warriors, a fate similar to the one that alternative art usually receives in Pakistan.

We are not introduced to the characters murdered in the first scene so the audience feels little connection to them, instead we are immediately intrigued by the masked figure (with a completely bandaged face) who completes his ‘work’ in seconds and then drives off in the cab he arrived in to the upbeat sound of “Do Pal Ka Ye Jeevan” by The Vital Signs, 80’s pop stars of Pakistan whose lead singer, Junaid Jamshed left music and became a fairly radical and mysogynist preacher under the tutelage of the Tableeghi Jamaat.

The masked figure’s next stop is the Unity Faith Discipline Sign on the outskirts of Islamabad. It is the motto of Pakistan given to it by the founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the lack of all three in today’s Pakistan is evident, though dreamers still aspire to “Jinnah’s Pakistan”. Retro radio news footage in the background reminds us that “Pakistan’s very existence depended on a powerful military”. The masked man’s encounter with the police officer in the next scene is telling, though unsurprising to the average Pakistani. After hearing a confession of the crime of five murders the policeman is unperturbed and repeatedly tells the murderer to get lost, though he is certainly not averse to taking money from him.

One interesting and poignant aspect of the film is the different archetypes of a woman played powerfully by Malika Zafar. She alternately plays a beggar, a victim of domestic abuse, a speaker at a socio-political forum and a prostitute. I felt these archetypes lacked a fully empowered woman, even though there are few examples of such women in Pakistan. An appearance as a goddess would probably result in a blasphemy charge.

Returning to the central character played by Uns Mufti, his mask of bandages is finally removed by the woman to reveal that he is a young film maker who still has demons to battle, though the dream/experience is behind him. The amount of emotion Mufti manages to express just through his eyes is amazing, and he explains in one scene that the reason for the bandages is because he feels his head might explode. Perhaps the strangest thing about the surrealism in this film is the ability of a Pakistani to easily relate to it.

The perversity of a television anchor is played masterfully by Omar Khalid Butt. His eagerness to portray a suicide (live!) on TV is a good representation of the media fetish for violence, and the breakdown of the waiter in response to a lack of water, gas and electricity is a reflection of the daily miseries of the public. His dreams of a messiah leader and his taking out his frustrations on his wife illustrate the cycle of horror that perpetuates problems.

Certainly Anima State is a dark film, but the recognition and reflection of our fears on screen is almost a relief. When one character exclaims that this story does not make any sense, you want to comfort him and emphatically agree. This film is so raw, and the expression of these themes so necessary that I truly wish it could be screened in the country it is meant for, but so far Anima State has found no release in Pakistan and after the Rafi Peer International Film Festival’s insistence on watering it down before exhibiting it, and the director’s subsequent refusal to do so, it seems unlikely to be screened in Pakistan.

In the final scene the question seems to be: where can we escape to? And is it a real escape if the demons are allowed to grow unfettered? Won’t they follow us wherever we go? Can we escape through film?

“Mujhe yahan se itni duur le jao ke mujhe yahan ka khwab bhi na aaye” (Take me so far from here that I am not even able to dream of this place is the final thought of the film and one that would undoubtedly resonate with a lot of Pakistani youth. The desire to escape Pakistan is almost universally prevalent amongst the youth, and when this cannot be done physically, the consolation is to retreat to happier places via film.

“Anima: The part of the psyche that is directed inward and in touch with the subconscious

State: Condition, situation or country.”

In a tranquil scene of an outdoor cafe the opening scene of the murder of five is as mundane as the daily violence that plagues this country. The difference, however, is that these are targets who are usually safe from much randomness. Their blood-speckled belongings – smart phones, shades, a designer bag and foreign clothing – reveal their backgrounds: the Elite of Pakistan, hated by some simply for what they are born with, and on occasion, because of what they do with that privilege.

Interestingly the young group that gets shot are also the stars of Slackistan, the director Hammad Khan’s first film that received mixed reviews, a ban in Pakistan and some ire for its focus on the country’s slackers. Later in the film “the tweeter” meets the central character, resulting in him getting beaten up by these Keyboard Warriors, a fate similar to the one that alternative art usually receives in Pakistan.

We are not introduced to the characters murdered in the first scene so the audience feels little connection to them, instead we are immediately intrigued by the masked figure (with a completely bandaged face) who completes his ‘work’ in seconds and then drives off in the cab he arrived in to the upbeat sound of “Do Pal Ka Ye Jeevan” by The Vital Signs, 80’s pop stars of Pakistan whose lead singer, Junaid Jamshed left music and became a fairly radical and mysogynist preacher under the tutelage of the Tableeghi Jamaat.

The masked figure’s next stop is the Unity Faith Discipline Sign on the outskirts of Islamabad. It is the motto of Pakistan given to it by the founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the lack of all three in today’s Pakistan is evident, though dreamers still aspire to “Jinnah’s Pakistan”. Retro radio news footage in the background reminds us that “Pakistan’s very existence depended on a powerful military”. The masked man’s encounter with the police officer in the next scene is telling, though unsurprising to the average Pakistani. After hearing a confession of the crime of five murders the policeman is unperturbed and repeatedly tells the murderer to get lost, though he is certainly not averse to taking money from him.

One interesting and poignant aspect of the film is the different archetypes of a woman played powerfully by Malika Zafar. She alternately plays a beggar, a victim of domestic abuse, a speaker at a socio-political forum and a prostitute. I felt these archetypes lacked a fully empowered woman, even though there are few examples of such women in Pakistan. An appearance as a goddess would probably result in a blasphemy charge.

Perhaps the strangest thing about the surrealism in this film is the ability of a Pakistani to completely relate to it

Returning to the central character played by Uns Mufti, his mask of bandages is finally removed by the woman to reveal that he is a young film maker who still has demons to battle, though the dream/experience is behind him. The amount of emotion Mufti manages to express just through his eyes is amazing, and he explains in one scene that the reason for the bandages is because he feels his head might explode. Perhaps the strangest thing about the surrealism in this film is the ability of a Pakistani to easily relate to it.

The perversity of a television anchor is played masterfully by Omar Khalid Butt. His eagerness to portray a suicide (live!) on TV is a good representation of the media fetish for violence, and the breakdown of the waiter in response to a lack of water, gas and electricity is a reflection of the daily miseries of the public. His dreams of a messiah leader and his taking out his frustrations on his wife illustrate the cycle of horror that perpetuates problems.

Certainly Anima State is a dark film, but the recognition and reflection of our fears on screen is almost a relief. When one character exclaims that this story does not make any sense, you want to comfort him and emphatically agree. This film is so raw, and the expression of these themes so necessary that I truly wish it could be screened in the country it is meant for, but so far Anima State has found no release in Pakistan and after the Rafi Peer International Film Festival’s insistence on watering it down before exhibiting it, and the director’s subsequent refusal to do so, it seems unlikely to be screened in Pakistan.

In the final scene the question seems to be: where can we escape to? And is it a real escape if the demons are allowed to grow unfettered? Won’t they follow us wherever we go? Can we escape through film?

“Mujhe yahan se itni duur le jao ke mujhe yahan ka khwab bhi na aaye” (Take me so far from here that I am not even able to dream of this place is the final thought of the film and one that would undoubtedly resonate with a lot of Pakistani youth. The desire to escape Pakistan is almost universally prevalent amongst the youth, and when this cannot be done physically, the consolation is to retreat to happier places via film.