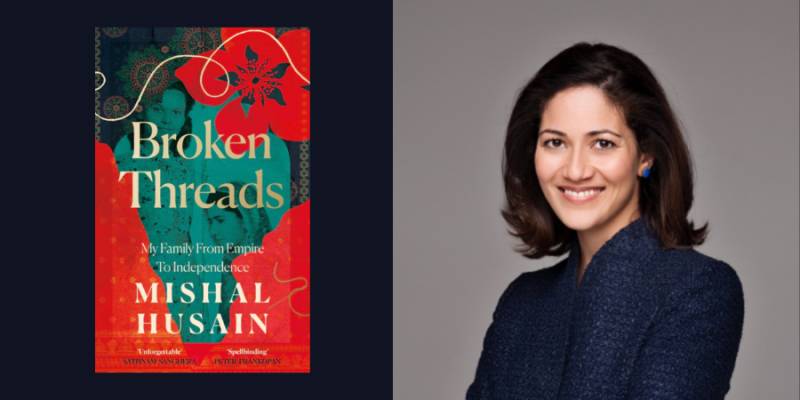

‘Broken Threads’ is a riveting history of British television news anchor Mishal Husain's family before and after the Partition.

Born in England to a father who had come to work for the National Health Service (NHS) and a mother who had followed suit, Mishal says she became conscious of the deep roots of her English friends at boarding school and realised she had no such roots of her own. Her parents were part of an expatriate community. This and a sari given as a wedding gift, fueled Mishal to discover her roots which led to her writing ‘Broken Threads: My family from Empire to Independence’.

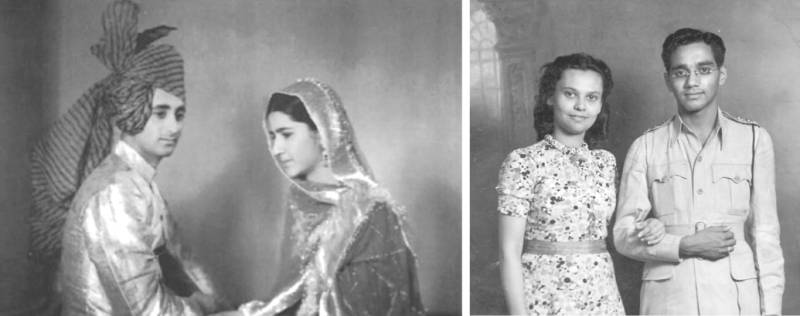

The book takes us back into the lives of her great-grand parents but mostly focuses on her four grandparents. Her maternal grandparents: Shahid and Tahirah, and her paternal grandparents, Mumtaz and Mary. She writes that her father’s parents had a life of different complexities. This is because they had married across different religious and ethnic lines, he was a Muslim from Multan in the province of Punjab, part of present-day Pakistan and she was a Catholic from the South-East of India. Similarly, Shahid had an illustrious career as the aide to the last Chief of the British-era Indian Army namely, Auckinleck. According to Shahid the time of partition was a time of remarkable leadership and also of ‘small men playing with the destiny of millions.’ Mishal writes that it was a time in which women’s lives were changing and thus her two grandmothers’ experiences and opportunities were very different from those of their mothers.

Tahirah left recorded cassettes of her memories for her grandchildren which helped Mishal in the research for ‘Broken Threads’. Mumtaz left an unpublished memoir which was helpful in writing the book as well. Shahid had published his own book on the topic of Partition since 1857. And Mary’s memories were retrieved from her sister Anne. When going through Tahirah’s cassettes, one quote that Mishal picked up, that struck a chord in my heart was: “Countries have their problems, whether they are ruled by others or by people that actually belong, and nothing is perfect. All I know is that the life I had before Partition of India was as beautiful and rich as it was afterwards.” Tahirah’s comment leaves us to wonder, what would have happened had Partition not taken place and how wise a decision it was. But these are all conjectures, because the truth, as Mishal writes in her book is that led by Jinnah and Nehru under Mountbatten’s leadership – Partition did occur, and all the consequences of it — killing, looting, a disputed Kashmir — did happen. Mishal writes about each of these events in some detail to make sure a reader unaccustomed to the history of the sub-continent understands the Partition of 1947. However, for myself these parts of the book were a little bit like revising my ‘O’ levels Pakistan Studies course.

Mishal writes how Jinnah, who is thought to be responsible for the partition, actually fought for a united post-independence India, that protected the Muslim-majority areas from rule of the national majority.

Mishal skillfully writes about the noble Mary Quinn who was the daughter of an Irishman with his younger Hindu wife; sagacious Tahirah; genius Shahid who trained at Sandhurst and then later on set-up Pakistan’s intelligence agency; and Mumtaz Husain, a doctor hailing from Multan who saw all the atrocities of the 1947 Partition. She explains the lives of each grandparent so carefully that the reader feels they are part of them – intertwined with their life stories. Whether you are reading about Mary’s nursing profession, Mumtaz’s time learning to be a doctor away from home or Shahid’s and Tahirah’s time with Auckinleck, and their fond memories, Mishal’s storytelling is excellent. It seems that she has put her experience of years reporting for the BBC to good use, while writing this book. It is an excellent source of positive material on not just Mishal’s ancestors but also on the partition and Jinnah’s critical role in it. As a counterpart to Nehru, Jinnah’s challenges were possibly much greater, given that the British, especially Mountbatten, sided with the Congress party leader. Mishal writes how Jinnah, who is thought to be responsible for the partition, actually fought for a united post-independence India, that protected the Muslim-majority areas from rule of the national majority. This plan was out right rejected by Nehru, who preferred the idea of partition to sharing power with Jinnah. Husain tries to imagine what would have occurred if Gandhi, and not Nehru, had been the leader of Congress – what if a different outcome could have been taken place?

Mishal ends the book writing: “Perhaps, then, the threads are more frayed than broken, because stories have been handed down in countless families, creating an oral link with the past. Today those tales connect people like me with those who went before, but taken together they also reveal bonds across borders, which one day might be more than memories.”

‘Broken Threads’ is a monumental achievement, chronicling not just Mishal’s history but for that of the sub-continent. It is well-written, with flair, full of anecdotes and historical facts and is fascinating read for all those who wish to learn about Indo-Pakistan.