In a clear break from almost a decade of mutual mistrust and disenchantment, both the US and Afghanistan now seem inclined to reboot their relations with Pakistan on sturdier and more transparent footings.

Coupled with changes in civilian leadership in Afghanistan and military leadership in Pakistan, the existing wave of bonhomie is anchored in Pakistan’s resolve to eliminate all shades of terrorist non-state actors from its territory, as manifested by Operations Zarb-e-Azb and Khyber I and II.

However, to consolidate our ties with Kabul and Washington, we should rethink and permanently alter our existing conceptions of power to protect or advance our interests in Afghanistan.

To great acclaim, noted American political scientist Joseph Nye has identified three specific varieties of power: hard power, economic power, and soft power. Each of these forms of power represents a unique tool at one state’s disposal to shape the actions of another. Hard power concerns the use of force by a state to coerce another state to submit to its will. Economic power is the ability to incentivize compliance by offering economic rewards to another state for its support. Soft power is premised on the concept of co-option and the ability to convince a state and its leadership to do what another state wants. Through elements like cultural convergence and defense diplomacy encompassing nonviolent military programs, Nye forcefully contends that it is possible to mould the decision-making of another state in a way that produces favorable outcomes for a particular state.

Much to our detriment, for far too long—stretching back to the 1970s—we have primarily relied on hard power to gain influence in Afghanistan while failing to harness other types of power to our advantage. Our future policies, therefore, should not be tainted by our prior mistakes and miscalculations. Instead, by limiting our use of hard power to situations of permissible self-defense under international law, a mix of mutually beneficial economic initiatives such as expanding the scope of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement and implementing the CASA-1000 energy agreement inked earlier this month will contribute significantly to enhanced mutual trust and internal stability in both the countries. As will the exercise of soft power through defense diplomacy including Pakistan’s outstanding offer to train Afghan security forces besides arming an Infantry Brigade.

Our counter-productive and irrational policies of resorting to non-state actors in the past to force favorable changes in Afghanistan have already brought heaps of inner turmoil and international scorn upon us leading many Western analysts to castigate Pakistan for its ‘duplicity’ in the global fight against terrorism. The latest Pentagon ‘Report on Progress toward Peace and Stability in Afghanistan’ continues to accuse Pakistan of using militants as instruments of hard power. Encouragingly, though, by sharing evidence establishing Pakistan’s zero-tolerance for all non-state actors including the Haqqani network during the ongoing military operations, Chief of the Army Staff General Raheel Sharif did much to blunt this narrative in his interactions with top US administration and defense officials in Washington. Accordingly, following the meeting of US-Pakistan Defense Consultative Group last week, the US has reaffirmed that Pakistani military operations have ‘disrupted the militants’ and agreed to continue providing security assistance for Pakistan’s counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency requirements.

The general shift in our posture vis-à-vis Afghanistan has been duly acknowledged by the US and Afghanistan not least because it affirms our commitment to uphold bedrock international law norms of respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity of other states, and our international obligations to eliminate terrorist non-state actors and their safe havens from our territory.

For their part, the US and Afghanistan should reciprocate by assuaging Pakistan’s legitimate concerns: Afghanistan must vigorously act against militant elements using its territory to destabilize Pakistan by launching and aiding cross-border terrorism, demonstrably reassure Pakistan that it will not allow its territory to be used as India’s proxy, and cooperate in developing robust joint border management mechanisms; the US should be sensitive to the realities of longstanding regional rivalries as it forges firmer ties with India during President Obama’s upcoming visit to New Delhi and resets its relations with Pakistan and Afghanistan in the backdrop of its formal troop drawdown from the latter’s territory following a draining full-blown military engagement for well over a decade.

Given the historical animosities and chronic suspicions bedeviling various South Asian relationships, genuine opportunities for conciliation remain a rarity. Pakistan, Afghanistan and the US, therefore, must not squander the current window of opportunity that could be a boon for much needed regional security and prosperity in the immediate and long-term.

The writer is a lawyer. He can be reached at as2ez@virginia.edu

Coupled with changes in civilian leadership in Afghanistan and military leadership in Pakistan, the existing wave of bonhomie is anchored in Pakistan’s resolve to eliminate all shades of terrorist non-state actors from its territory, as manifested by Operations Zarb-e-Azb and Khyber I and II.

However, to consolidate our ties with Kabul and Washington, we should rethink and permanently alter our existing conceptions of power to protect or advance our interests in Afghanistan.

To great acclaim, noted American political scientist Joseph Nye has identified three specific varieties of power: hard power, economic power, and soft power. Each of these forms of power represents a unique tool at one state’s disposal to shape the actions of another. Hard power concerns the use of force by a state to coerce another state to submit to its will. Economic power is the ability to incentivize compliance by offering economic rewards to another state for its support. Soft power is premised on the concept of co-option and the ability to convince a state and its leadership to do what another state wants. Through elements like cultural convergence and defense diplomacy encompassing nonviolent military programs, Nye forcefully contends that it is possible to mould the decision-making of another state in a way that produces favorable outcomes for a particular state.

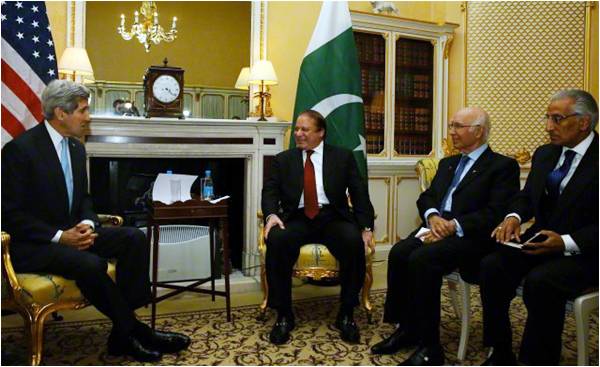

The US has agreed to continue providing security assistance for Pakistan's counter-terrorism requirements

Much to our detriment, for far too long—stretching back to the 1970s—we have primarily relied on hard power to gain influence in Afghanistan while failing to harness other types of power to our advantage. Our future policies, therefore, should not be tainted by our prior mistakes and miscalculations. Instead, by limiting our use of hard power to situations of permissible self-defense under international law, a mix of mutually beneficial economic initiatives such as expanding the scope of the Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement and implementing the CASA-1000 energy agreement inked earlier this month will contribute significantly to enhanced mutual trust and internal stability in both the countries. As will the exercise of soft power through defense diplomacy including Pakistan’s outstanding offer to train Afghan security forces besides arming an Infantry Brigade.

Our counter-productive and irrational policies of resorting to non-state actors in the past to force favorable changes in Afghanistan have already brought heaps of inner turmoil and international scorn upon us leading many Western analysts to castigate Pakistan for its ‘duplicity’ in the global fight against terrorism. The latest Pentagon ‘Report on Progress toward Peace and Stability in Afghanistan’ continues to accuse Pakistan of using militants as instruments of hard power. Encouragingly, though, by sharing evidence establishing Pakistan’s zero-tolerance for all non-state actors including the Haqqani network during the ongoing military operations, Chief of the Army Staff General Raheel Sharif did much to blunt this narrative in his interactions with top US administration and defense officials in Washington. Accordingly, following the meeting of US-Pakistan Defense Consultative Group last week, the US has reaffirmed that Pakistani military operations have ‘disrupted the militants’ and agreed to continue providing security assistance for Pakistan’s counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency requirements.

The general shift in our posture vis-à-vis Afghanistan has been duly acknowledged by the US and Afghanistan not least because it affirms our commitment to uphold bedrock international law norms of respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity of other states, and our international obligations to eliminate terrorist non-state actors and their safe havens from our territory.

For their part, the US and Afghanistan should reciprocate by assuaging Pakistan’s legitimate concerns: Afghanistan must vigorously act against militant elements using its territory to destabilize Pakistan by launching and aiding cross-border terrorism, demonstrably reassure Pakistan that it will not allow its territory to be used as India’s proxy, and cooperate in developing robust joint border management mechanisms; the US should be sensitive to the realities of longstanding regional rivalries as it forges firmer ties with India during President Obama’s upcoming visit to New Delhi and resets its relations with Pakistan and Afghanistan in the backdrop of its formal troop drawdown from the latter’s territory following a draining full-blown military engagement for well over a decade.

Given the historical animosities and chronic suspicions bedeviling various South Asian relationships, genuine opportunities for conciliation remain a rarity. Pakistan, Afghanistan and the US, therefore, must not squander the current window of opportunity that could be a boon for much needed regional security and prosperity in the immediate and long-term.

The writer is a lawyer. He can be reached at as2ez@virginia.edu