Kuchh roz Naseer aao chalo ghar mein raha jaaye

Logon ko ye shikva hai ke ghar par nahin milta

(Come, in our house for a few days Naseer, let us now remain

For he is not found at home, the people complain)

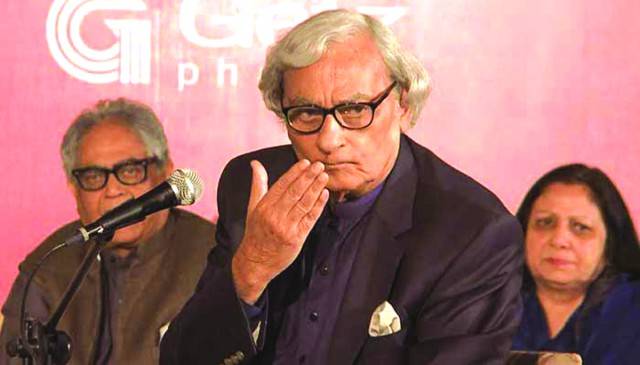

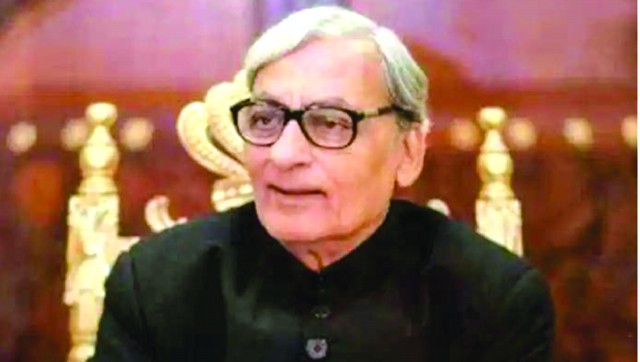

One had still not fully come to terms with the death of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi last Christmas, when news came on January 10, more than a month ago, early into this new year, that Naseer Turabi, too, had left us in Karachi, succumbing to a heart-attack at 75. He was buried in Karachi on the following day.

Voh humsafar tha magar us se hum-navai na thi

(He was a fellow traveler but we did not speak in unison)

This popular ghazal is perhaps known to all. But how many of us know that Naseer Turabi was its author? In 2011, the popular television drama Humsafar (Fellow Traveler) attained spectacular popularity, while the soundtrack of this drama will still be seated firmly in the mind of everybody. This ghazal of Naseer Turabi was used as a part of the soundtrack of the drama and reached the heights of popularity.

Vo ham-safar tha magar us se ham-navai na thi

Ke dhoop chhaon ka aalam raha judai na thi

Adaavaten theen, taghaful tha, ranjishen theen bahut

Bichhadne vaale mein sab kuchh tha, bevafai na thi

(He was a fellow traveler but we did not speak in unison

That there was a state of sun and shade, but not separation

There were animosities, negligence and a lot of indignation

The one who parted possessed everything, treachery was an exception)

If we review the words of this ghazal and the story of the drama serial Humsafar, one feels as if this ghazal is very much written for this drama, which was based on the story of two such characters who though were a part of each other’s lives, but due to issues and misunderstandings in their life they were forced to separate from each other. After the ghazal Voh humsafar tha magar us se humnavai na thi became famous, it was observed that whenever Turabi participated in any function, the participants used to request him to recite it – though even today for many people, especially young people, its identity is very much the drama Humsafar. However if we analyze its background, this ghazal was written by Turabi after the creation of Bangladesh. Indeed ghazals are always written in this very manner. Direct matters are addressed in poems while in the ghazal one tries to make the reader understand their point by allusions, rhymes and additional things. For example if one considers the ghazal of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, he too had written on the separation of East Pakistan from Pakistan Khoon ke dhabbe dhulenge kitni barsaaton ke baad (After how many rains will the blood stains wash away). This ghazal can be opened up to multiple meanings in that it has been very much composed for a lover; though a ghazal has its own treatment so it should always be seen from this view. In the same manner, Turabi, too, wrote this ghazal in the background of the emergence of Bangladesh.

In 1980 at least three decades before this ghazal became famous as the soundtrack of the Humsafar drama in the voice of Quratulain Balouch, it was sung first of all by Abida Parveen. She used to live in the same mohalla as Turabi and both were on genial terms with each other, after which this ghazal was moulded into song. One also remembers that Turabi himself while mentioning this soundtrack once had said that when it was decided to use this ghazal for the drama, the production house did not even know who its author was. Undoubtedly, Naseer Turabi was a very good poet and a big name, but he did not immediately become as popular as a few other poets. One can get a measure of this from the fact that the identity of a good poet is very much that his poetry reaches the people and becomes popular before his name.

Who was Naseer Turabi? He was born in Hyderabad Deccan on 15 June 1945 to eminent religious scholar and khateeb Allama Rashid Turabi. After the creation of Pakistan, his family migrated to Karachi in Pakistan, where he grew up. He obtained an MA degree in Journalism from the University of Karachi in 1968. When he was studying at school, he began his journey with debates and disputations. In one such competition, he obtained third position, upon which one of his teachers remarked to him, “Next time bring a better speech written by your father,” after which Turabi quit discussion. Afterwards, upon being asked the reason by the school principal, he replied that “if I get first position my father is given credit and if I obtain third position even then my father’s name is defamed. So I want to change my name, after which I went towards poetry.”

For him, life was easy in that he could have extended his father’s work because he had many qualities of oratory. He always used to say that a tiny plant will be unable to even breathe below such a giant tree. He further said that whatever he had achieved in terms of literature and poetry is before everyone today. If Turabi liked a verse or work of someone, he would promote it. To care about people, to help and worry for them was a part of his self. That is why he always used to say that one should love humans and use things. Though a few people also think that a certain contradiction in his personality and his critical vision with respect to work was the cause of differences with some people. This trait recently came to the fore when Turabi came down hard against his contemporaries Iftikhar Arif and the late Parveen Shakir on social and mainstream media.

His first volume of poetry Aks-e-Faryadi (The Supplicant’s Reflection) was published in 2000. Turabi’s other scholarly work Sheriyaat (Poetics) published in 2012 begins with the definition of a verse. He deemed 5 elements essential for composing poetry: a balanced temperament; study of poetry; familiarity with language; construction of imagination; and poetic drill. Then he classified 4 types of poets: great poet; important poet; congenial poet; and simple poet.

There were only 5 great Urdu poets according to him: Mir, Ghalib, Anees, Iqbal and Josh. Whereas among important poets he numbered 8 names: Yagana, Firaq, Faiz, Rashid, Miraji, Aziz Hamid Madni, Nasir Kazmi and Majeed Amjad. Critics of poetry and literature can dismiss this list or rearrange it to amend and add; but for a beginner of language and narration, and a fresh student of poetry, such a clear gradation and decisive division could prove very reassuring and useful.

The other chapters of the book have made their topics of discussion the prevalent genres of poetry, obsolete genres, correct dictation, pronunciation, masculinity and femininity, singular and plural, appendages, synonyms, prefixes and suffixes, commonly erroneous words and operative terminologies. And Turabi in his peculiar pleasant and playful manner has made these dry basic topics so interesting that if this book is handed to some grammar-sick person, they will not get up before finishing it.

His uncharitable opinions about Iftikhar Arif and Pareen Shakir notwithstanding, Naseer Turabi may forever be seen as the poet who never got his due in his lifetime, yet at least for a while his most popular ghazal will ensure that he is the focus of renewed attention as the South Asian Subcontinent prepares to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the emergence of Bangladesh later this year.

Vo ham-safar tha magar us se ham-navai na thi

Ke dhoop chhaon ka aalam raha judai na thi

Na apna ranj na auron ka dukh na tera malaal

Shab-e-firaq kabhi ham ne yuun ganvai na thi

Mohabbaton ka safar is tarah bhi guzra tha

Shikasta-dil the musafir shikasta-pai na thi

Adaavaten theen, taghaaful tha, ranjishen theen bahut

Bichhadne vaale mein sab kuchh tha, bevafai na thi

Bichhadte vaqt un aankhon mein thi hamari ghazal

Ghazal bhi vo jo kisi ko abhi sunai na thi

Kise pukaar raha tha vo doobta hua din

Sada to aai thi lekin koi duhai na thi

Kabhi ye haal ke donon mein yak-dili thi bahut

Kabhi ye marhala jaise ke aashnai na thi

Ajeeb hoti hai raah-e-suḳhan bhi dekh ‘Naseer’

Vahan bhi aa gaye aḳhir, jahan rasai na thi

(He was a fellow traveler but we did not speak in unison

That there was a state of sun and shade, but not separation

Neither my own grief nor the others’ distress, not even your sorrow

We had never squandered like this the night of separation

The journey of love had been spent too like this

The traveler was broken-hearted but his feet were not broken

There were animosities, negligence and a lot of indignation

The one who parted possessed everything, treachery was an exception

While parting those eyes had our ghazal

A ghazal indeed which we had yet not revealed in narration

To whom that sinking day was calling out

The shout was indeed heard but there was no appeal of desperation

Now this state that there was great concord between both

Then this stage as if there was no connection

Strange is the poetic way, see Naseer

We arrived there after all, where there was no entry)

All translations are by the writer. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader, currently based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

Logon ko ye shikva hai ke ghar par nahin milta

(Come, in our house for a few days Naseer, let us now remain

For he is not found at home, the people complain)

One had still not fully come to terms with the death of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi last Christmas, when news came on January 10, more than a month ago, early into this new year, that Naseer Turabi, too, had left us in Karachi, succumbing to a heart-attack at 75. He was buried in Karachi on the following day.

Voh humsafar tha magar us se hum-navai na thi

(He was a fellow traveler but we did not speak in unison)

This popular ghazal is perhaps known to all. But how many of us know that Naseer Turabi was its author? In 2011, the popular television drama Humsafar (Fellow Traveler) attained spectacular popularity, while the soundtrack of this drama will still be seated firmly in the mind of everybody. This ghazal of Naseer Turabi was used as a part of the soundtrack of the drama and reached the heights of popularity.

Vo ham-safar tha magar us se ham-navai na thi

Ke dhoop chhaon ka aalam raha judai na thi

Adaavaten theen, taghaful tha, ranjishen theen bahut

Bichhadne vaale mein sab kuchh tha, bevafai na thi

(He was a fellow traveler but we did not speak in unison

That there was a state of sun and shade, but not separation

There were animosities, negligence and a lot of indignation

The one who parted possessed everything, treachery was an exception)

If we review the words of this ghazal and the story of the drama serial Humsafar, one feels as if this ghazal is very much written for this drama, which was based on the story of two such characters who though were a part of each other’s lives, but due to issues and misunderstandings in their life they were forced to separate from each other. After the ghazal Voh humsafar tha magar us se humnavai na thi became famous, it was observed that whenever Turabi participated in any function, the participants used to request him to recite it – though even today for many people, especially young people, its identity is very much the drama Humsafar. However if we analyze its background, this ghazal was written by Turabi after the creation of Bangladesh. Indeed ghazals are always written in this very manner. Direct matters are addressed in poems while in the ghazal one tries to make the reader understand their point by allusions, rhymes and additional things. For example if one considers the ghazal of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, he too had written on the separation of East Pakistan from Pakistan Khoon ke dhabbe dhulenge kitni barsaaton ke baad (After how many rains will the blood stains wash away). This ghazal can be opened up to multiple meanings in that it has been very much composed for a lover; though a ghazal has its own treatment so it should always be seen from this view. In the same manner, Turabi, too, wrote this ghazal in the background of the emergence of Bangladesh.

After the ghazal Voh humsafar tha magar us se humnavai na thi became famous, it was observed that whenever Turabi participated in any function, the participants used to request him to recite it – though even today for many people, especially young people, its identity is very much the drama Humsafar

In 1980 at least three decades before this ghazal became famous as the soundtrack of the Humsafar drama in the voice of Quratulain Balouch, it was sung first of all by Abida Parveen. She used to live in the same mohalla as Turabi and both were on genial terms with each other, after which this ghazal was moulded into song. One also remembers that Turabi himself while mentioning this soundtrack once had said that when it was decided to use this ghazal for the drama, the production house did not even know who its author was. Undoubtedly, Naseer Turabi was a very good poet and a big name, but he did not immediately become as popular as a few other poets. One can get a measure of this from the fact that the identity of a good poet is very much that his poetry reaches the people and becomes popular before his name.

Who was Naseer Turabi? He was born in Hyderabad Deccan on 15 June 1945 to eminent religious scholar and khateeb Allama Rashid Turabi. After the creation of Pakistan, his family migrated to Karachi in Pakistan, where he grew up. He obtained an MA degree in Journalism from the University of Karachi in 1968. When he was studying at school, he began his journey with debates and disputations. In one such competition, he obtained third position, upon which one of his teachers remarked to him, “Next time bring a better speech written by your father,” after which Turabi quit discussion. Afterwards, upon being asked the reason by the school principal, he replied that “if I get first position my father is given credit and if I obtain third position even then my father’s name is defamed. So I want to change my name, after which I went towards poetry.”

For him, life was easy in that he could have extended his father’s work because he had many qualities of oratory. He always used to say that a tiny plant will be unable to even breathe below such a giant tree. He further said that whatever he had achieved in terms of literature and poetry is before everyone today. If Turabi liked a verse or work of someone, he would promote it. To care about people, to help and worry for them was a part of his self. That is why he always used to say that one should love humans and use things. Though a few people also think that a certain contradiction in his personality and his critical vision with respect to work was the cause of differences with some people. This trait recently came to the fore when Turabi came down hard against his contemporaries Iftikhar Arif and the late Parveen Shakir on social and mainstream media.

His first volume of poetry Aks-e-Faryadi (The Supplicant’s Reflection) was published in 2000. Turabi’s other scholarly work Sheriyaat (Poetics) published in 2012 begins with the definition of a verse. He deemed 5 elements essential for composing poetry: a balanced temperament; study of poetry; familiarity with language; construction of imagination; and poetic drill. Then he classified 4 types of poets: great poet; important poet; congenial poet; and simple poet.

His first volume of poetry Aks-e-Faryadi (The Supplicant’s Reflection) was published in 2000. Turabi’s other scholarly work Sheriyaat (Poetics) published in 2012 begins with the definition of a verse

There were only 5 great Urdu poets according to him: Mir, Ghalib, Anees, Iqbal and Josh. Whereas among important poets he numbered 8 names: Yagana, Firaq, Faiz, Rashid, Miraji, Aziz Hamid Madni, Nasir Kazmi and Majeed Amjad. Critics of poetry and literature can dismiss this list or rearrange it to amend and add; but for a beginner of language and narration, and a fresh student of poetry, such a clear gradation and decisive division could prove very reassuring and useful.

The other chapters of the book have made their topics of discussion the prevalent genres of poetry, obsolete genres, correct dictation, pronunciation, masculinity and femininity, singular and plural, appendages, synonyms, prefixes and suffixes, commonly erroneous words and operative terminologies. And Turabi in his peculiar pleasant and playful manner has made these dry basic topics so interesting that if this book is handed to some grammar-sick person, they will not get up before finishing it.

His uncharitable opinions about Iftikhar Arif and Pareen Shakir notwithstanding, Naseer Turabi may forever be seen as the poet who never got his due in his lifetime, yet at least for a while his most popular ghazal will ensure that he is the focus of renewed attention as the South Asian Subcontinent prepares to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the emergence of Bangladesh later this year.

Vo ham-safar tha magar us se ham-navai na thi

Ke dhoop chhaon ka aalam raha judai na thi

Na apna ranj na auron ka dukh na tera malaal

Shab-e-firaq kabhi ham ne yuun ganvai na thi

Mohabbaton ka safar is tarah bhi guzra tha

Shikasta-dil the musafir shikasta-pai na thi

Adaavaten theen, taghaaful tha, ranjishen theen bahut

Bichhadne vaale mein sab kuchh tha, bevafai na thi

Bichhadte vaqt un aankhon mein thi hamari ghazal

Ghazal bhi vo jo kisi ko abhi sunai na thi

Kise pukaar raha tha vo doobta hua din

Sada to aai thi lekin koi duhai na thi

Kabhi ye haal ke donon mein yak-dili thi bahut

Kabhi ye marhala jaise ke aashnai na thi

Ajeeb hoti hai raah-e-suḳhan bhi dekh ‘Naseer’

Vahan bhi aa gaye aḳhir, jahan rasai na thi

(He was a fellow traveler but we did not speak in unison

That there was a state of sun and shade, but not separation

Neither my own grief nor the others’ distress, not even your sorrow

We had never squandered like this the night of separation

The journey of love had been spent too like this

The traveler was broken-hearted but his feet were not broken

There were animosities, negligence and a lot of indignation

The one who parted possessed everything, treachery was an exception

While parting those eyes had our ghazal

A ghazal indeed which we had yet not revealed in narration

To whom that sinking day was calling out

The shout was indeed heard but there was no appeal of desperation

Now this state that there was great concord between both

Then this stage as if there was no connection

Strange is the poetic way, see Naseer

We arrived there after all, where there was no entry)

All translations are by the writer. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader, currently based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com