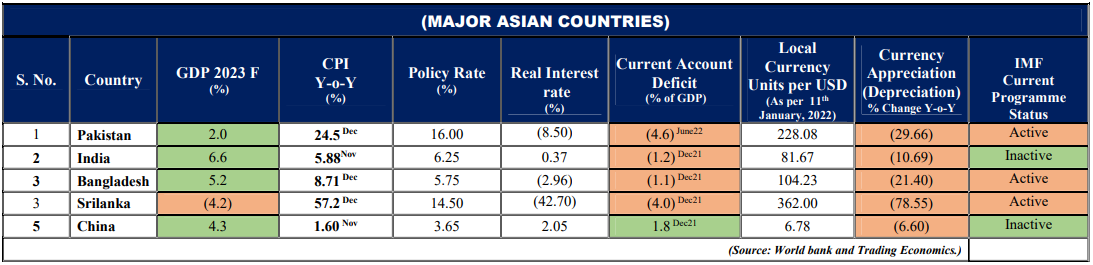

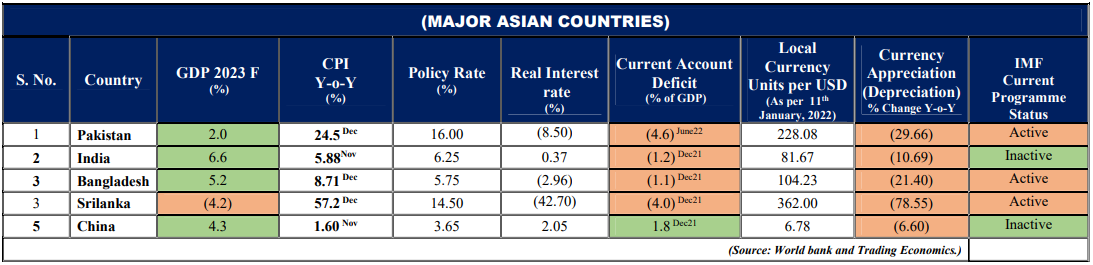

As per news doing the rounds, the IMF has asked Pakistan for an interest rate hike in order to reduce the gap between the rate of inflation and prevailing interest rates. The measure is in line with the IMF’s other conditionalites that aim to curb demand in the economy and reduce the fiscal deficit. However, the SBP already hiked rates back in January, and any further increase will add to inflationary pressures.

Source: Tola Associates (Figures for Dec 2022)

The interest rate conundrum

As per an article published by the IMF, “While there are many different interest rates in financial markets, the policy interest rate set by a country’s central bank provides the key benchmark for borrowing costs in the country’s economy. Central banks vary the policy rate in response to changes in the economic cycle and to steer the country’s economy by influencing many different (mainly short-term) interest rates. Higher policy rates provide incentives for saving, while lower rates motivate consumption and reduce the cost of business investment.”

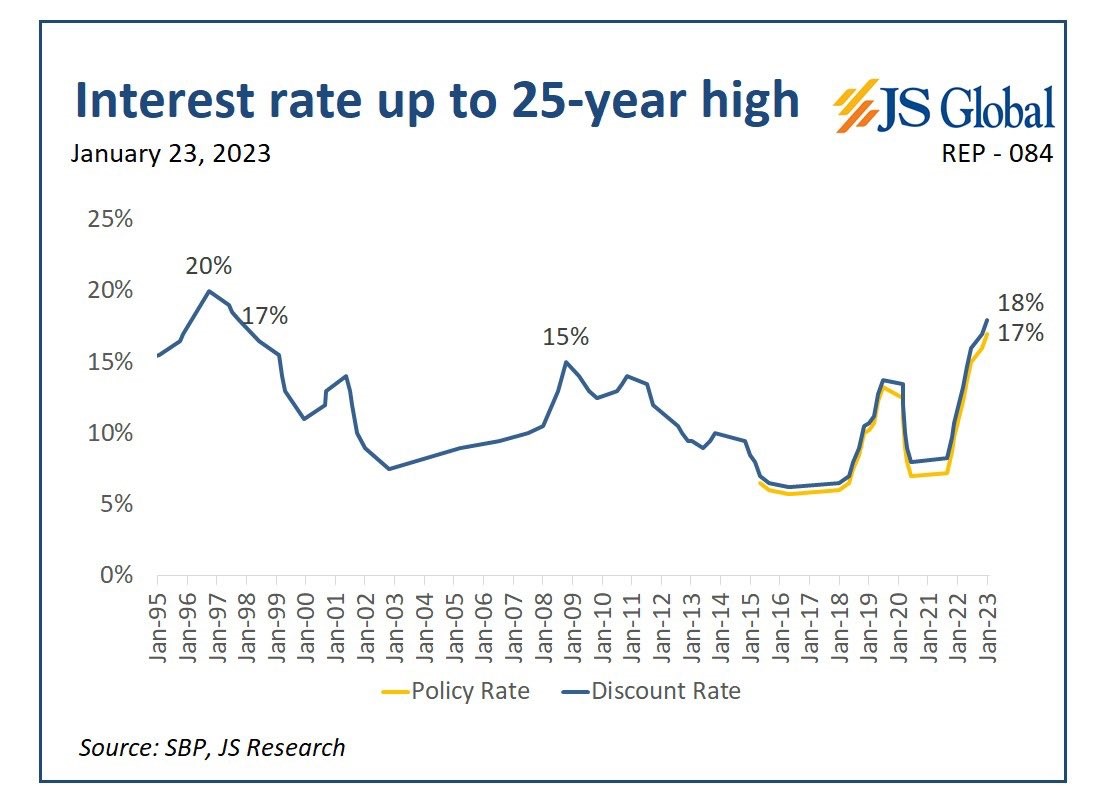

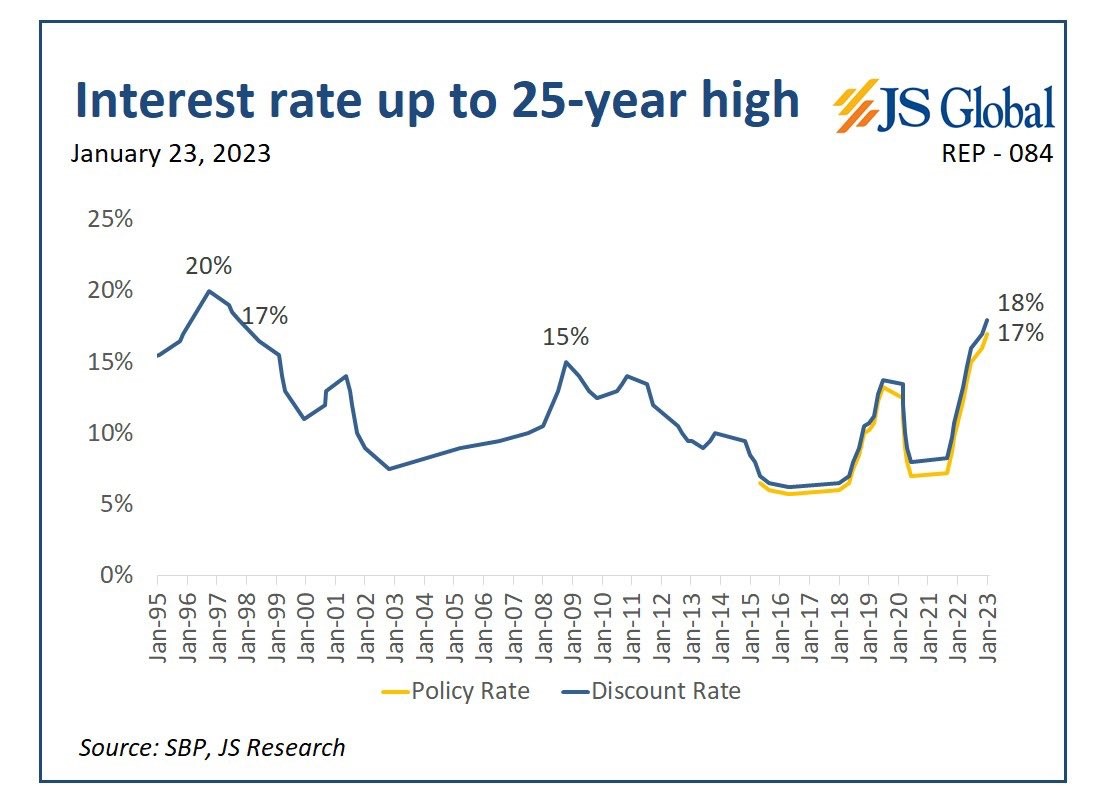

Pakistan has consistently increased the policy rate over the course of last one year with the latest being on January 23, 2023.

“The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to increase the policy rate by 100 basis points to 17 percent. The committee noted that inflationary pressures are persisting and continue to be broad-based. If these remain unchecked, they could feed into higher inflation expectations over a longer than anticipated period. The MPC stressed that it is critical to anchor inflation expectations and achieve the objective of price stability to support sustainable growth in the future,” read the SBP press release on 23rd January.

However, experts have doubts about the efficacy of the contractionary measures in tackling inflationary pressures as Pakistan is facing a wave of primarily cost-push inflation driven by relatively inelastic imports of fuel and food items.

“Pakistan does not have a demand problem. It has today and in the past been plagued by systemic supply-side issues. Whether that was a dilapidated energy chain, narrow revenue base, limited human resources or low productivity. Restricting imports, capital controls or pushing the economy into a recession was never going to be more than a short-term Hail Mary. Time has almost run out,” writes Mustafa O. Pasha, Chief Investment Officer at Lakson Investments, in an article for Business Recorder.

Further, it is argued that there is no room left to squeeze consumer discretionary demand as successive rate hikes have conquered that front. Additionally, higher rates might not necessarily translate into greater savings as a large chunk of the undocumented and informal economy doesn’t respond to monetary measures in a systematic manner.

https://twitter.com/MOPasha84/status/1626936333745934337

A double-edged sword

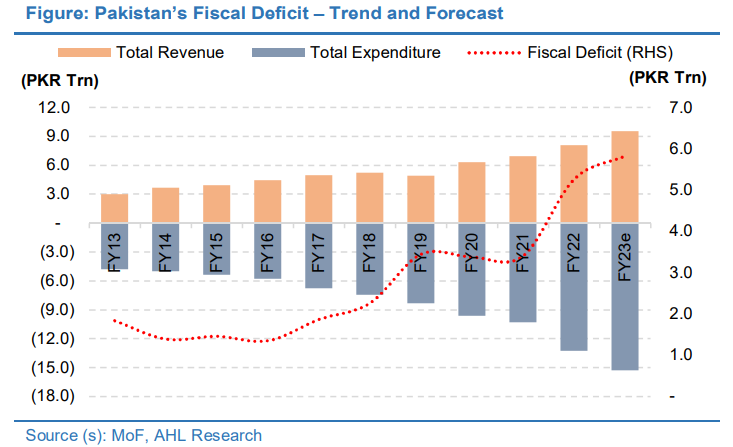

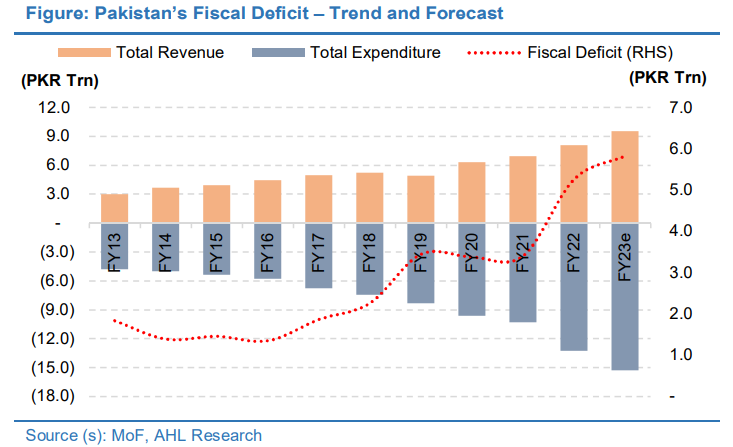

In spite of the recent rate hikes, inflation has not decreased, but the hikes have led to a bigger debt servicing cost in the current fiscal year which, at Rs5.2 trillion, is 52% of the total budget. Further, coupled with defense expenditure, it constitutes around 70% of the country’s budget.

The majority of debt servicing flows through to domestic lenders, and in case of a rate hike there would be an incremental burden on the federation and the fiscal deficit can expand.

Source: ARHL

Therefore, it can amplify the voices calling for a restructuring of Pakistan’s domestic public debt which stands at around 50 percent of GDP. In case of a significant rate hike, restructuring might as well become a tool in managing the fiscal deficit and examples like that of Ghana may encourage the government to consider it as a viable option.

“The West African nation is restructuring 137.3 billion cedis ($11.3 billion) of domestic loans as part of an overhaul of almost all of its 575.5 billion cedis of debt. The authorities had targeted an 80% subscription rate for the domestic-debt restructuring to be deemed successful and the offer deadline was postponed five times to improve participation” reported Bloomberg.

However, experts have also pointed out to alternatives that can serve to reduce the fiscal burden of debt servicing without disrupting the domestic banking system.

The case being presented is that around 40% of the domestic debt is owed to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and majority of the interest earnings on this debt will route back to the national treasury.

“The interest payments that are made by the finance ministry to the SBP make their way back to the government in the form of non-tax revenue when the State Bank makes a profit on those loans and then pays it back to the government in the form of a dividend. This basically means, the government is paying itself for a loan it gives itself – money from one hand into the other and back into the first,” writes journalist Ariba Shahid in an article for Profit.

However, there is another group of lenders, commercial banks, that leverage depositor money to lend to the government.

“Approximately Rs 14 trillion of bank deposits are interest bearing where banks are bound to pay 15.5 percent (150 bps below the policy rate), with exception of Islamic deposits where the return is slightly lower. Here, banks are raising deposits at minimum 15.5 percent and lending it to the government at 17-18 percent. If interest rates move up further, banks’ margins will remain the same while depositors will benefit incrementally,” read an article by finance and economy journalist, Ali Khizar.

In the same article, Ali has suggested that the government can raise taxes on these depositors and bridge the fiscal gap through incremental revenues. The downside to this would be in the shape of disincentivizing savings and encouraging the informal economy which can further aggravate the country’s economic woes.

Therefore, it can be accurately stated that those in power are faced with limited options, with every path ultimately leading to further economic hardship and suffering.

Source: Tola Associates (Figures for Dec 2022)

The interest rate conundrum

As per an article published by the IMF, “While there are many different interest rates in financial markets, the policy interest rate set by a country’s central bank provides the key benchmark for borrowing costs in the country’s economy. Central banks vary the policy rate in response to changes in the economic cycle and to steer the country’s economy by influencing many different (mainly short-term) interest rates. Higher policy rates provide incentives for saving, while lower rates motivate consumption and reduce the cost of business investment.”

Pakistan has consistently increased the policy rate over the course of last one year with the latest being on January 23, 2023.

“The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to increase the policy rate by 100 basis points to 17 percent. The committee noted that inflationary pressures are persisting and continue to be broad-based. If these remain unchecked, they could feed into higher inflation expectations over a longer than anticipated period. The MPC stressed that it is critical to anchor inflation expectations and achieve the objective of price stability to support sustainable growth in the future,” read the SBP press release on 23rd January.

However, experts have doubts about the efficacy of the contractionary measures in tackling inflationary pressures as Pakistan is facing a wave of primarily cost-push inflation driven by relatively inelastic imports of fuel and food items.

“Pakistan does not have a demand problem. It has today and in the past been plagued by systemic supply-side issues. Whether that was a dilapidated energy chain, narrow revenue base, limited human resources or low productivity. Restricting imports, capital controls or pushing the economy into a recession was never going to be more than a short-term Hail Mary. Time has almost run out,” writes Mustafa O. Pasha, Chief Investment Officer at Lakson Investments, in an article for Business Recorder.

Further, it is argued that there is no room left to squeeze consumer discretionary demand as successive rate hikes have conquered that front. Additionally, higher rates might not necessarily translate into greater savings as a large chunk of the undocumented and informal economy doesn’t respond to monetary measures in a systematic manner.

https://twitter.com/MOPasha84/status/1626936333745934337

A double-edged sword

In spite of the recent rate hikes, inflation has not decreased, but the hikes have led to a bigger debt servicing cost in the current fiscal year which, at Rs5.2 trillion, is 52% of the total budget. Further, coupled with defense expenditure, it constitutes around 70% of the country’s budget.

The majority of debt servicing flows through to domestic lenders, and in case of a rate hike there would be an incremental burden on the federation and the fiscal deficit can expand.

Source: ARHL

Therefore, it can amplify the voices calling for a restructuring of Pakistan’s domestic public debt which stands at around 50 percent of GDP. In case of a significant rate hike, restructuring might as well become a tool in managing the fiscal deficit and examples like that of Ghana may encourage the government to consider it as a viable option.

“The West African nation is restructuring 137.3 billion cedis ($11.3 billion) of domestic loans as part of an overhaul of almost all of its 575.5 billion cedis of debt. The authorities had targeted an 80% subscription rate for the domestic-debt restructuring to be deemed successful and the offer deadline was postponed five times to improve participation” reported Bloomberg.

However, experts have also pointed out to alternatives that can serve to reduce the fiscal burden of debt servicing without disrupting the domestic banking system.

The case being presented is that around 40% of the domestic debt is owed to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and majority of the interest earnings on this debt will route back to the national treasury.

“The interest payments that are made by the finance ministry to the SBP make their way back to the government in the form of non-tax revenue when the State Bank makes a profit on those loans and then pays it back to the government in the form of a dividend. This basically means, the government is paying itself for a loan it gives itself – money from one hand into the other and back into the first,” writes journalist Ariba Shahid in an article for Profit.

However, there is another group of lenders, commercial banks, that leverage depositor money to lend to the government.

“Approximately Rs 14 trillion of bank deposits are interest bearing where banks are bound to pay 15.5 percent (150 bps below the policy rate), with exception of Islamic deposits where the return is slightly lower. Here, banks are raising deposits at minimum 15.5 percent and lending it to the government at 17-18 percent. If interest rates move up further, banks’ margins will remain the same while depositors will benefit incrementally,” read an article by finance and economy journalist, Ali Khizar.

In the same article, Ali has suggested that the government can raise taxes on these depositors and bridge the fiscal gap through incremental revenues. The downside to this would be in the shape of disincentivizing savings and encouraging the informal economy which can further aggravate the country’s economic woes.

Therefore, it can be accurately stated that those in power are faced with limited options, with every path ultimately leading to further economic hardship and suffering.