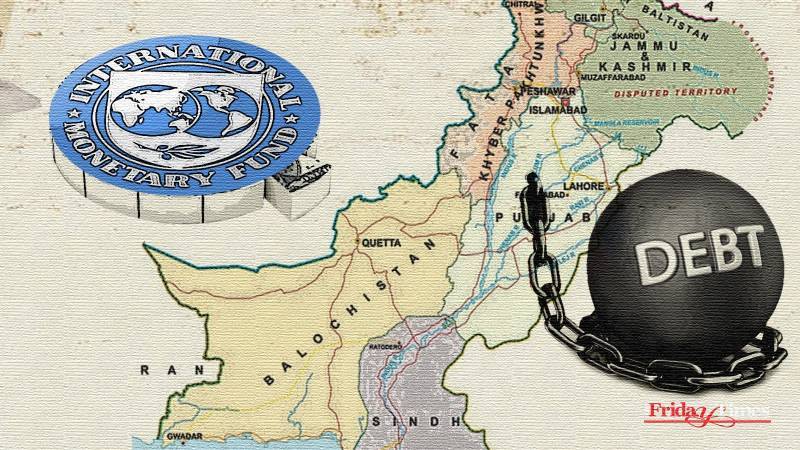

At last, Islamabad has successfully secured the $7 billion stand-by agreement (SBA), but the call for celebrations is too early as the situation is not as promising as it looks. The economy is running in circles as the decision-makers in Islamabad use the same old play book to manage economic affairs. The detailed International Monetary Fund (IMF) Stand by Agreement (SBA) report, released in October, acknowledges substantial progress that Islamabad has made over the year, but the optimism is misplaced. The burgeoning rise in domestic and foreign debt has reached Rs71 trillion, which poses an existential challenge to Pakistan's economic sustainability. Islamabad's extensive reliance on debt to run its affairs is skewing Pakistan economic solvency. Pakistan’s growing dependence on foreign loans, especially from the lender-of-last-resort IMF and friendly countries such as China, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, prompts a critical examination of whether these foreign funds are truly beneficial or pose a risk to the country’s economic stability.

Over the past few decades, Islamabad has increasingly turned to foreign loans to bridge its fiscal deficits. Although these myopic measures have provided short-term relief, their long-term implications are becoming more apparent. Unlike domestic borrowing, foreign debt is usually denominated in foreign currency, which creates an additional burden as debt servicing must be done in dollars. Islamabad's debt servicing accounted for 74.8% of Pakistan's GDP in 2023, depleting Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves, which are already under stress. The issue of debt repayment is squeezing the government's ability to provide social welfare or infrastructural development to the citizens. The fundamental question is whether Pakistan can manage its growing foreign debt without sacrificing economic sovereignty.

Another question arises on the duplicate role of multilateral institutions like the IMF, whose stringent neoliberal descriptions, like adopting austerity measures, subsidy cuts, and tax reforms, have failed to bring Pakistan out of the economic bridge. Their prescription of the usual austerity measures, including cuts and tax reforms that aim to reduce fiscal deficits, have disproportionately impacted the general population. The 1994 Independent Power Producer policy (IPPs) has wreaked havoc on Pakistani consumers today, accumulating Rs2.6 trillion of circular debt. The increase in electricity tariffs has reduced people's propensity to spend as it has dented household income. The increase in energy demand in the coming season of winter will increase energy prices, making the cost of living for ordinary citizens higher than ever. The trade of supplying gas and electricity to households will lead to lower industrial production prospects, dampening economic growth. In such a situation, the government finds itself constrained and unable to pursue citizen-friendly policies, as it must prioritise meeting the conditions set by its foreign creditors.

The core problem is Pakistan’s addiction to debt as it continues to rely on friendly nations like China, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, to provide immense assistance in the form of loan rollover, cash deposits, and oil deferment, helping the government manage its fiscal obligations. However, this form of foreign support has its own set of challenges. While friendly nations may not impose the same conditionality as the IMF, dependence on such loans can lead to a subtle form of influence over national policies. For instance, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the associated China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) have brought in significant investments and significantly added to Pakistan’s external debt. CPEC has an unprecedented dividend to Pakistan but the fact remains that Islamabad has a burgeoning debt repayment obligation to Beijing. Thus, this delicate balancing act between benefiting from foreign investment and managing the growing debt obligations is becoming an irreparable challenge for Pakistan’s economic planners.

The impact of foreign debt on Pakistan’s long-term growth prospects is equally concerning. A large portion of the foreign loans obtained by the government is used to service existing debt rather than being channeled into productive investments that could spur economic growth. As more resources are funneled toward meeting debt repayments, less remains for sectors like education, healthcare, and infrastructure development. Islamabad is trapped in a vicious cycle of continuous borrowing to meet its day-to-day expenditure, thereby increasing its future debt burden. The reliance on external inflows also discourages efforts to improve domestic revenue generation.If policymakers in Islamabad continue to follow this trajectory of financing the budget by squeezing the already-burdened tax base and using a strict approach to widen it, no result will be obtained. Lack of fiscal discipline is the main hindrance to the country's long-term financial viability.

The problem is not gaining foreign debt but about an unsustainable approach, leading Pakistan into another short-term fiscal crisis. A more sustainable, prudent strategy is needed to avoid long-term dependence. The Pakistani policymakers must implement a homegrown agenda of reform whereby they diversify the export base by promoting strategic sectors in the economy like agriculture, SMEs, and textiles, which can create opportunities for foreign direct investment (FDI). Strategic sectors like manufacturing, information technology, mining can increase foreign exchange reserves via foreign direct investment (FDI). Similarly, concerted efforts must be made to formalise white elephants like agriculture, real estate and retails which can significantly reduce government's dependence on external borrowing. It is imperative that the interest rate must be lowered further from 17.5% to spur Pakistan’s stunted growth. In short, no nation has ever risen on the account of debt accumulation.

While foreign debt can provide immediate financial relief, its long-term, negative implications are profound for Pakistan’s economic sovereignty and stability. The onus lies on decision makers in Islamabad to prudently weigh the short-term benefits of foreign loans against the potential loss of economic independence and the growing debt burden. The path of Pakistan’s sustainable growth and prosperity lies only in a self-reliant economy capable of generating its resources, rather than relying on foreign debt.