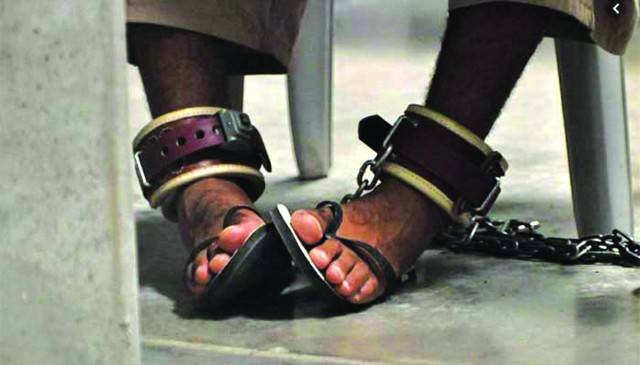

On Monday, the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) released a joint report titled “Criminalising Torture in Pakistan: The need for an effective legal framework.” Published a day after a teenager was reported to have died in police custody in Peshawar, the report sheds light on the lack of appropriate legislation against torture in Pakistan.

“Torture by police is rampant in Pakistan,” said former senator and Pakistan Peoples Party senior leader Farhatullah Babar at the online panel discussion organized for the launch of the report. “Nothing can be accepted as a defence for this crime.”

As a party to international treaties, Pakistan has an obligation to criminalise torture. However, attempts to do so have historically failed. A bill tabled by Senator Sherry Rehman is currently pending in the Senate. If passed, it would make torture by law enforcement agencies a crime for the first time in Pakistan. But first, it needs to be approved by both the Senate and National Assembly.

“Human Rights Minister Shireen Mazari brought up this issue with the prime minister. We have good hope that in a few weeks an anti-torture bill will be presented in front of the Cabinet,” declared Ministry of Human Rights Director-General Muhammad Hassan Mangi.

Pakistan has human rights obligations and the country has ratified international treaties prohibiting the use of torture, such as the United Nations Convention Against Torture, or the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). These treaties are legally binding, and oblige Pakistan to implement anti-torture legislation.

“Under the UNCAT, it is an obligation for state parties to provide a definition of torture which must be reflected in the criminal law of the state party,” declared United Nations Convention Against Torture Member Diego Rodriguez-Pinzon at the launch of the report.

“If you commit an act of violence, you will not have a safe haven and you can be tried and convicted anywhere for your crime,” added the founder and executive director of Justice Project Pakistan, Sarah Belal. “This principle under the UNCAT is truly extraordinary.”

In June 2020, Pakistan submitted a voluntary pledge to the United Nations, stating that an earlier bill on the same issue — Torture, Custodial Death and Custodial Rape (Prevention and Punishment) Bill 2018 — had reached the consideration stage of the National Assembly/Senate. The pledge was submitted as part of Pakistan’s candidacy to the UN Human Rights Council. Despite these promises, the legal situation remains the same.

“The aim of the Convention against Torture is to protect people,” says OMCT Secretary General Gerald Staberock. “It is key that States who are parties to the Convention implement it in their national legislations. Otherwise, these obligations are nothing but empty promises.”

Most of the time in Pakistan, perpetrators are left unpunished and victims are not recognized. A day prior to the launch of the report, a seventh grade student was reported to have died in police custody in Peshawar.

Court seeks report on consular assistance for Pakistanis imprisoned in Iran

The Lahore High Court (LHC) on Tuesday directed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) to submit a detailed report on the efforts made to provide consular assistance to Pakistanis imprisoned in Iran in order to secure their repatriation.

“The state is responsible to represent these prisoners forcefully as required by law to expedite their repatriation and ensure consular assistance at all stages of their imprisonment,” argued Barrister Sarah Belal while apprising the court on the importance of expediting the repatriation of Pakistani prisoners. She appreciated the efforts of MoFA’s Iran desk in holding consistent meetings with their counterparts in Tehran to bring back prisoners but noted that a consular policy was still pending.

According to a reply submitted by MoFA in the previous hearing, 102 Pakistanis are presently imprisoned in Iran. Of these, 65 prisoners have already been convicted and are eligible for repatriation to their home country under a Prisoner Transfer Agreement signed by the two nations in 2014. The agreement allows prisoners to complete their sentences in their native countries.

Due to the lack of a uniform consular policy, Pakistani citizens imprisoned abroad lack consular support and adequate legal representation, often suffering due process violations such as long periods of detention without charge or trial. The majority of Pakistani prisoners in foreign jails are arrested for non-lethal crimes such as drug trafficking, theft and violation of immigration laws.

“Torture by police is rampant in Pakistan,” said former senator and Pakistan Peoples Party senior leader Farhatullah Babar at the online panel discussion organized for the launch of the report. “Nothing can be accepted as a defence for this crime.”

As a party to international treaties, Pakistan has an obligation to criminalise torture. However, attempts to do so have historically failed. A bill tabled by Senator Sherry Rehman is currently pending in the Senate. If passed, it would make torture by law enforcement agencies a crime for the first time in Pakistan. But first, it needs to be approved by both the Senate and National Assembly.

“Human Rights Minister Shireen Mazari brought up this issue with the prime minister. We have good hope that in a few weeks an anti-torture bill will be presented in front of the Cabinet,” declared Ministry of Human Rights Director-General Muhammad Hassan Mangi.

Pakistan has human rights obligations and the country has ratified international treaties prohibiting the use of torture, such as the United Nations Convention Against Torture, or the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). These treaties are legally binding, and oblige Pakistan to implement anti-torture legislation.

“Under the UNCAT, it is an obligation for state parties to provide a definition of torture which must be reflected in the criminal law of the state party,” declared United Nations Convention Against Torture Member Diego Rodriguez-Pinzon at the launch of the report.

“If you commit an act of violence, you will not have a safe haven and you can be tried and convicted anywhere for your crime,” added the founder and executive director of Justice Project Pakistan, Sarah Belal. “This principle under the UNCAT is truly extraordinary.”

In June 2020, Pakistan submitted a voluntary pledge to the United Nations, stating that an earlier bill on the same issue — Torture, Custodial Death and Custodial Rape (Prevention and Punishment) Bill 2018 — had reached the consideration stage of the National Assembly/Senate. The pledge was submitted as part of Pakistan’s candidacy to the UN Human Rights Council. Despite these promises, the legal situation remains the same.

“The aim of the Convention against Torture is to protect people,” says OMCT Secretary General Gerald Staberock. “It is key that States who are parties to the Convention implement it in their national legislations. Otherwise, these obligations are nothing but empty promises.”

Most of the time in Pakistan, perpetrators are left unpunished and victims are not recognized. A day prior to the launch of the report, a seventh grade student was reported to have died in police custody in Peshawar.

Court seeks report on consular assistance for Pakistanis imprisoned in Iran

The Lahore High Court (LHC) on Tuesday directed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) to submit a detailed report on the efforts made to provide consular assistance to Pakistanis imprisoned in Iran in order to secure their repatriation.

“The state is responsible to represent these prisoners forcefully as required by law to expedite their repatriation and ensure consular assistance at all stages of their imprisonment,” argued Barrister Sarah Belal while apprising the court on the importance of expediting the repatriation of Pakistani prisoners. She appreciated the efforts of MoFA’s Iran desk in holding consistent meetings with their counterparts in Tehran to bring back prisoners but noted that a consular policy was still pending.

According to a reply submitted by MoFA in the previous hearing, 102 Pakistanis are presently imprisoned in Iran. Of these, 65 prisoners have already been convicted and are eligible for repatriation to their home country under a Prisoner Transfer Agreement signed by the two nations in 2014. The agreement allows prisoners to complete their sentences in their native countries.

Due to the lack of a uniform consular policy, Pakistani citizens imprisoned abroad lack consular support and adequate legal representation, often suffering due process violations such as long periods of detention without charge or trial. The majority of Pakistani prisoners in foreign jails are arrested for non-lethal crimes such as drug trafficking, theft and violation of immigration laws.