It would be ironic, if it were not so unfortunate. Just as Pakistan and China dive headlong into an aggressive plan to expand road networks from Gwadar to Gilgit to create a route for cargo, the very people who transport those goods went on strike. They were angry that the Sindh High Court had said that heavy vehicles will be restricted in the Karachi city jurisdiction during the daytime. And so a wrinkle exposed just how quickly the best laid plans can be threatened.

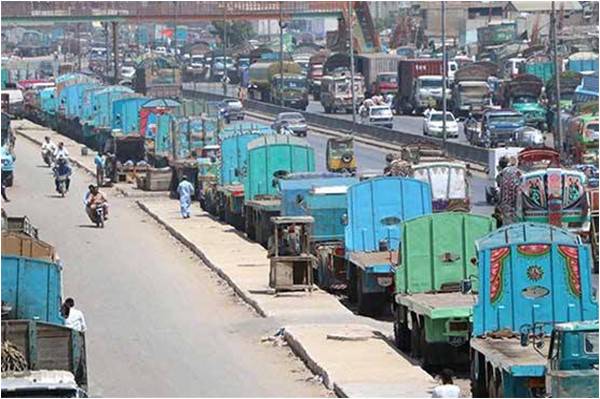

By May 17, the strike had entered its ninth day, paralysing trade across the country. About 7,000 to 8,000 containers and goods carriers with raw material, imported food and other items travel daily from the Karachi Port to Port Qasim, Landhi and the Korangi industrial areas. Worries mounted that Ramadan food supplies would be hamstrung. Exporters declared that without the trucks in operation, Rs56 billion in exports and Rs157 billion in imports were being affected. They pegged the loss at Rs23 billion to the economy. An estimated 70,000 shipping containers were stuck at the Karachi port, disrupting operations. To give you a sense of the bulwark, consider this: the Pakistan United Transporters Panel was joined by 14 other bodies.

The Sindh High Court, for its part, was responding to a petition that sought to limit the movement of heavy vehicles on the city’s roads and through residential localities. In other words, traffic congestion, risk of accidents and the public’s inconvenience were given as reasons. This issue, which has cropped up from time to time, during the tenure of several governments, thus gives any planner a sense of just how complicated an entire city’s machinery is. Indeed, Karachi has long needed a planning solution for the movement from the port but due to disruptions in governance has never been able to tackle it.

The goods carriers were directed to use routes that were longer, but emptier. This didn’t sit well with them. So to prove a point, they went on strike, opting to not do any business at all. And while the strike was called off by Wednesday, just as we went to press, the people at the helm of affairs and perhaps in China must have taken note of this incident.

At another level, the strike went to the heart of a philosophical debate; the strike was seen by some stakeholders as a means to achieving their interest. But what of the interest of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in the future? What of the interest of the residents of Karachi? Or indeed the interest of the residents of any part of Pakistan where major economic activity will be or is already taking place but to their detriment?

The strike has clearly demonstrated several lessons: First, that the existing system of transporting goods from Karachi to other parts of the country is affecting its residential areas and Karachi’s urban planners need to work on solutions. Those solutions will have to do a fine balancing act between the interests of commerce and citizen. Second, as CPEC projects start rolling out there is always a possibility that certain stakeholders will resist them if they perceive their mechanisms not to benefit them. Third, how will the people and their government see eye to eye on common or national or economic interest and which one will get thrown under the bus?

As with such conflicts, our courts have to pick up the slack for a lack of urban planning. Of course, these battles can be fought out in court; the SHC can be overruled by the Supreme Court and the ban could be reversed. On the other hand, the government can reach a settlement and cave into demands just to stop the economy from hurting.

Everyone will have to start waking up to the fact that it at least cannot be business as usual now in the very least because CPEC is at our doorstep. For years, shipping containers have travelled on long vehicles through residential localities. The traffic police don’t look the other way as such, but they did allow the movement to continue as long as they were “taken onboard” in many instances often the result was that accidents took place and people died. That was the human cost; there is the environment to consider too.

If such strikes or pressures keep bubbling up the economy will continues to suffer. Importers who will see their shipments delayed will increase prices. Exporters who will miss sending their orders will pass on the cost to the consumer. The country’s trade deficit would continue to be a pain for economic managers and Pakistan’s domestic issue would be on display for the entire world to see. It will be hard to dismiss the numbers if you will want to issue statements that are aimed at boosting investor confidence.

The reality is that Pakistan will continue to face issues like the transporters’ strike. People will continue protesting water shortages and power outages. This is because no government has found a permanent solution to them in recent times. Thousands of megawatts would be added, but the inner workings of companies responsible for transmitting and distributing this electricity would remain inefficient.

The country is as good as its people and Pakistan has failed to invest in its citizens. Ishaq Dar will boast greater revenue, but what he won’t talk about is how a lack of education and awareness is holding back potential. That social contract will be crucial. Pakistan may see better and wider roads, together with greater electricity and a host of new companies, but the reality will remain unchanged unless there is an investment in education. Unprofessionalism, corruption and outright ignorance has crept so far into the system that it may take a long time to turn them around. Unfortunately, governments tend to focus on quantifiable measures and not on quality. The stakes, however, are much higher with CPEC on the horizon.

By May 17, the strike had entered its ninth day, paralysing trade across the country. About 7,000 to 8,000 containers and goods carriers with raw material, imported food and other items travel daily from the Karachi Port to Port Qasim, Landhi and the Korangi industrial areas. Worries mounted that Ramadan food supplies would be hamstrung. Exporters declared that without the trucks in operation, Rs56 billion in exports and Rs157 billion in imports were being affected. They pegged the loss at Rs23 billion to the economy. An estimated 70,000 shipping containers were stuck at the Karachi port, disrupting operations. To give you a sense of the bulwark, consider this: the Pakistan United Transporters Panel was joined by 14 other bodies.

The strike went to the heart of a debate; the strike was seen by some stakeholders as a means to achieving their interest. But what of the interest of CPEC in the future? What of the residents of Karachi? Or indeed the interest of the residents of any part of Pakistan where major economic activity will be or is already taking place but to their detriment?

The Sindh High Court, for its part, was responding to a petition that sought to limit the movement of heavy vehicles on the city’s roads and through residential localities. In other words, traffic congestion, risk of accidents and the public’s inconvenience were given as reasons. This issue, which has cropped up from time to time, during the tenure of several governments, thus gives any planner a sense of just how complicated an entire city’s machinery is. Indeed, Karachi has long needed a planning solution for the movement from the port but due to disruptions in governance has never been able to tackle it.

The goods carriers were directed to use routes that were longer, but emptier. This didn’t sit well with them. So to prove a point, they went on strike, opting to not do any business at all. And while the strike was called off by Wednesday, just as we went to press, the people at the helm of affairs and perhaps in China must have taken note of this incident.

At another level, the strike went to the heart of a philosophical debate; the strike was seen by some stakeholders as a means to achieving their interest. But what of the interest of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in the future? What of the interest of the residents of Karachi? Or indeed the interest of the residents of any part of Pakistan where major economic activity will be or is already taking place but to their detriment?

The strike has clearly demonstrated several lessons: First, that the existing system of transporting goods from Karachi to other parts of the country is affecting its residential areas and Karachi’s urban planners need to work on solutions. Those solutions will have to do a fine balancing act between the interests of commerce and citizen. Second, as CPEC projects start rolling out there is always a possibility that certain stakeholders will resist them if they perceive their mechanisms not to benefit them. Third, how will the people and their government see eye to eye on common or national or economic interest and which one will get thrown under the bus?

As with such conflicts, our courts have to pick up the slack for a lack of urban planning. Of course, these battles can be fought out in court; the SHC can be overruled by the Supreme Court and the ban could be reversed. On the other hand, the government can reach a settlement and cave into demands just to stop the economy from hurting.

Everyone will have to start waking up to the fact that it at least cannot be business as usual now in the very least because CPEC is at our doorstep. For years, shipping containers have travelled on long vehicles through residential localities. The traffic police don’t look the other way as such, but they did allow the movement to continue as long as they were “taken onboard” in many instances often the result was that accidents took place and people died. That was the human cost; there is the environment to consider too.

If such strikes or pressures keep bubbling up the economy will continues to suffer. Importers who will see their shipments delayed will increase prices. Exporters who will miss sending their orders will pass on the cost to the consumer. The country’s trade deficit would continue to be a pain for economic managers and Pakistan’s domestic issue would be on display for the entire world to see. It will be hard to dismiss the numbers if you will want to issue statements that are aimed at boosting investor confidence.

The reality is that Pakistan will continue to face issues like the transporters’ strike. People will continue protesting water shortages and power outages. This is because no government has found a permanent solution to them in recent times. Thousands of megawatts would be added, but the inner workings of companies responsible for transmitting and distributing this electricity would remain inefficient.

The country is as good as its people and Pakistan has failed to invest in its citizens. Ishaq Dar will boast greater revenue, but what he won’t talk about is how a lack of education and awareness is holding back potential. That social contract will be crucial. Pakistan may see better and wider roads, together with greater electricity and a host of new companies, but the reality will remain unchanged unless there is an investment in education. Unprofessionalism, corruption and outright ignorance has crept so far into the system that it may take a long time to turn them around. Unfortunately, governments tend to focus on quantifiable measures and not on quality. The stakes, however, are much higher with CPEC on the horizon.