On October 8, 2022, Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa addressed a batch of graduating cadets, and commented, “As a leader, you need to have courage and ability to take difficult decisions and then accept full responsibility”. His statement tells us a lot about ideas of the Marshalls who have reigned over our country.

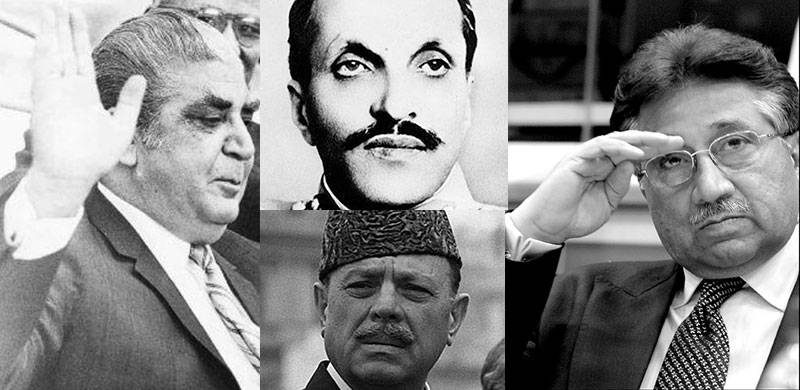

The advent of Marshalls began in 1958, when Iskander Mirza joined with Ayub Khan, proclaimed Marshal Law over the country, and abrogated the 1956 constitution. With Iskander Mirza practically futile, Ayub Khan punted him out after 20 days, and claimed full power for himself.

Ayub Khan had a difficult decision to make -- to legitimize his power seizure, which had no backing of the law.

Justice Muhammad Munir, who had a history of weaving the destruction of Pakistan’s democracy, came to the rescue. An international law theory by Hans Kelsen was borrowed to chastise Ayub’s government in a judgment that horrified even the theory giver, who expressed his disapproval over how his theory was used.

Ayub’s difficult decision was sustained, and the military general ruled happily for nearly 10 years.

On leaving in 1969, he ushered in his comrade, General Muhammad Yahya Khan, who shared his predecessor’s resoluteness. After conducting the fairest elections in Pakistan’s history in 1970, Yahya was bothered with a troublesome decision: to not transfer power to the Awami League, which commanded a majority in the elections.

The army couldn’t stay away from power for long. After a brief interlude of ‘Civilian Marshal Law’, led by Premier Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, General Muhammad Ziaul Haq took hold of the country’s reigns in 1977.

Zia remained in power for almost a decade. Bhutto was pushed to the gallows in a ‘Judicial Murder’. Shoddy party-less elections were conducted. A shroud of Islam was worn to placate the masses and appease certain groups at the cost of uncertainty in laws. “The Zia regime has been the most repressive in Pakistan’s history, precisely because it had the most to repress,” wrote Benazir Bhutto, daughter of the assassinated premier.

The repressive army chief, nonetheless, won a losing battle with his shrewd measures.

After Zia, the army drove the country from the back seat, only to arrive at loggerheads again with democracy in 1999.

Nawaz Sharif’s backstepping from Kargil had angered the then General Parvez Musharraf, who had prepared relentlessly for a war. The army resented Musharraf’s dismal by Sharif in 1999, and took hold of the country in an unconstitutional manner.

Musharraf pushed Sharif out in a conspiracy case and proclaimed a new constitutional order, this time, treading carefully on legal lines, with the help of legal eagles like Sharifuddin Pirzada.

The annals of history show that Pakistan’s army has taken hard stances and tough decisions and has remained steadfast in their verdicts, yet these decisions have cost Pakistan its democracy.

The more recent involvement of the army in politics was questioned by Supreme Court judge, Qazi Faez Isa. There were rumours that the establishment had handed out money to an irate crowd chaired by Khadim Rizvi to cool off the situation. “The constitution emphatically prohibits members of the armed forces from engaging in any kind of political activity, which includes supporting a political party, faction or individual,” Justice Isa stated in Suo Moto Case No. 7/2017, famously known as Faizabad dharna case.

A reference of corruption was brought up against Isa, and he defended his suit before his friends, stressing that the reference was a political consequence of the dharna case.

There may or may not be veracity in his allegation, but the insinuation says a lot about the army’s stronghold in politics.

It is alleged that Imran Khan’s government was a product of the establishment. He ruled for four years with a slim majority of 176 in the National Assembly.

Khan has acknowledged this at multiple occasions. On October 12, 2022, while addressing a group of journalists, he said, “Our hands were tied. We were blackmailed from everywhere. Power wasn’t with us. Everyone knows where the power lies in Pakistan so we had to rely on them.”

Khan’s government withered as soon as the establishment stopped supporting him.

Bajwa’s October 5 assurance that “the armed forces have distanced themselves from politics and want to remain so.” may come as a relief to many. I hope General Bajwa takes the hard decision of renouncing entry into politics and stays true to it. If yes, he will be an example of someone who took a ‘difficult decision’ to bolster Pakistan’s democracy.

Seventy-four years back, while addressing the Royal Pakistan Air Force, Quaid-i-Azam exhorted, “You should have no hand in supporting this political party or that political party, this political leader or that political leader – this is not your business.” He left this world, and his words remained unfathomed.

The advent of Marshalls began in 1958, when Iskander Mirza joined with Ayub Khan, proclaimed Marshal Law over the country, and abrogated the 1956 constitution. With Iskander Mirza practically futile, Ayub Khan punted him out after 20 days, and claimed full power for himself.

Ayub Khan had a difficult decision to make -- to legitimize his power seizure, which had no backing of the law.

Justice Muhammad Munir, who had a history of weaving the destruction of Pakistan’s democracy, came to the rescue. An international law theory by Hans Kelsen was borrowed to chastise Ayub’s government in a judgment that horrified even the theory giver, who expressed his disapproval over how his theory was used.

Ayub’s difficult decision was sustained, and the military general ruled happily for nearly 10 years.

On leaving in 1969, he ushered in his comrade, General Muhammad Yahya Khan, who shared his predecessor’s resoluteness. After conducting the fairest elections in Pakistan’s history in 1970, Yahya was bothered with a troublesome decision: to not transfer power to the Awami League, which commanded a majority in the elections.

The army couldn’t stay away from power for long. After a brief interlude of ‘Civilian Marshal Law’, led by Premier Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, General Muhammad Ziaul Haq took hold of the country’s reigns in 1977.

Zia remained in power for almost a decade. Bhutto was pushed to the gallows in a ‘Judicial Murder’. Shoddy party-less elections were conducted. A shroud of Islam was worn to placate the masses and appease certain groups at the cost of uncertainty in laws. “The Zia regime has been the most repressive in Pakistan’s history, precisely because it had the most to repress,” wrote Benazir Bhutto, daughter of the assassinated premier.

The repressive army chief, nonetheless, won a losing battle with his shrewd measures.

After Zia, the army drove the country from the back seat, only to arrive at loggerheads again with democracy in 1999.

Nawaz Sharif’s backstepping from Kargil had angered the then General Parvez Musharraf, who had prepared relentlessly for a war. The army resented Musharraf’s dismal by Sharif in 1999, and took hold of the country in an unconstitutional manner.

Musharraf pushed Sharif out in a conspiracy case and proclaimed a new constitutional order, this time, treading carefully on legal lines, with the help of legal eagles like Sharifuddin Pirzada.

After Zia, the army drove the country from the back seat, only to arrive at loggerheads again with democracy in 1999.

The annals of history show that Pakistan’s army has taken hard stances and tough decisions and has remained steadfast in their verdicts, yet these decisions have cost Pakistan its democracy.

The more recent involvement of the army in politics was questioned by Supreme Court judge, Qazi Faez Isa. There were rumours that the establishment had handed out money to an irate crowd chaired by Khadim Rizvi to cool off the situation. “The constitution emphatically prohibits members of the armed forces from engaging in any kind of political activity, which includes supporting a political party, faction or individual,” Justice Isa stated in Suo Moto Case No. 7/2017, famously known as Faizabad dharna case.

A reference of corruption was brought up against Isa, and he defended his suit before his friends, stressing that the reference was a political consequence of the dharna case.

There may or may not be veracity in his allegation, but the insinuation says a lot about the army’s stronghold in politics.

It is alleged that Imran Khan’s government was a product of the establishment. He ruled for four years with a slim majority of 176 in the National Assembly.

Khan has acknowledged this at multiple occasions. On October 12, 2022, while addressing a group of journalists, he said, “Our hands were tied. We were blackmailed from everywhere. Power wasn’t with us. Everyone knows where the power lies in Pakistan so we had to rely on them.”

Khan’s government withered as soon as the establishment stopped supporting him.

Bajwa’s October 5 assurance that “the armed forces have distanced themselves from politics and want to remain so.” may come as a relief to many. I hope General Bajwa takes the hard decision of renouncing entry into politics and stays true to it. If yes, he will be an example of someone who took a ‘difficult decision’ to bolster Pakistan’s democracy.

Seventy-four years back, while addressing the Royal Pakistan Air Force, Quaid-i-Azam exhorted, “You should have no hand in supporting this political party or that political party, this political leader or that political leader – this is not your business.” He left this world, and his words remained unfathomed.