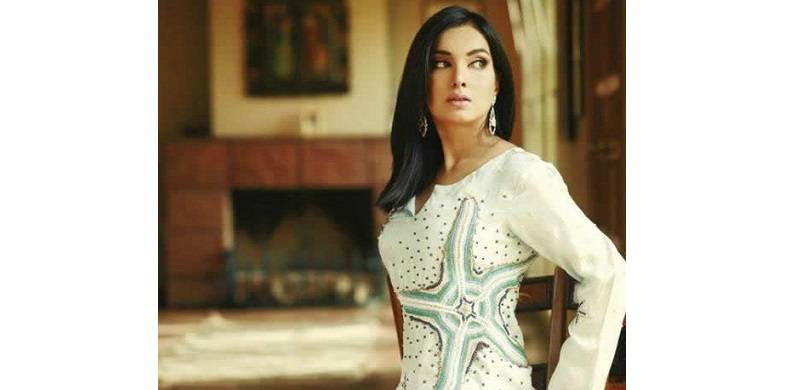

Aaminah Haq (Aaminah) was and still retains the title of being the most creative model of the fashion industry. The impact Aaminah Haq had, the influence her work had, and her legacy, remains unmatched. Like a wildfire she blazed her way into the industry, setting alight everything and everyone that came in her way, setting a benchmark of creativity and an attitude that paved the way for so many young models of today. ‘In the nineties, when I was a teenager, you couldn’t exactly say, “Hey, I want to be a model”, and receive a, “Oh great, how can we help you?” That wasn’t a conversation you really had.’

It took an aunt, Ayesha Tammy Haq, to convince her mother to let her do a shoot for Herald and that was all Aaminah needed to get her foot through the door, kick it down and stamp her footprint all over the industry.

But it wasn’t the glamour or the charm of being a model that hooked her initially. ‘I think for me, it was really about becoming more independent, becoming emancipated and choosing a path that was really my own.’ Being the daughter of a landlord, Aaminah struggled with what so many young people hailing from renowned families go through—living under their parents’ shadows.

Having grown up with her maternal family comprising of strong women who decided for themselves in terms of what they wanted to do with their lives, Aaminah’s conscientious decision to model was a means of having a sense of identity and creating her own brand without ever being referred to as somebody’s daughter. ‘I wanted to be Aaminah Haq and I wanted to construct that narrative on my own.’ Little did she know then the rippling waves her decision would send across the then infantile industry and the limitless abyss of creativity she would unleash.

Call it fate or call it luck, Aaminah met people who believed in what she wanted to do and helped her create the supermodel she eventually became. One of them would be Yahsir Waheed, who taught her the crucial things that make a model stand apart from the crowd. ‘When I started modelling, there were very few people who supported what I was doing. So he really helped me create my own stories, my own journey, whom to contact, which magazines to be in. He showed me the kind of model I wanted to be.’

Like-minded independent journalists like Fifi Haroon took notice of this young rebel and a wonderfully creative relationship blossomed. ‘Xtra was a ground-breaking magazine and we still don’t have anything like that today. What Fifi was able to publish and the work she was able to project, it was incredible.’ It was in Fifi that Aaminah would found the same mind-set: a model simply had to be much more than just a coat-hanger and it had to be about ‘embracing who you were’. And when Aaminah met Nabila and Tapu, there was no stopping her.

By then modelling for her had evolved from seeking an identity to establishing herself as something different as a woman. This was largely because she did not fit the modelling mould that had already been set: tall, lanky. Not that it mattered because she was going to go for everything with a clear goal in mind: to work on her terms.

This caused Aaminah to be one of the first to break an ancient societal rule that had obviously made its way into the modelling industry: Gora rung. ‘I would ask photographers why they were whitening me; that used to be my biggest bone of contention’. This was one major reason why Aaminah found a kindred spirit in Nabila who never tried to mould her into anything else. ‘Nabila really understood me and what I wanted to do, we were very clear about the parameters we wanted to set for ourselves.’

While understanding the need for makeup, Aaminah’s argument was simple—makeup had to be theatrical, it had to make a statement but it most certainly did not have to consist of seven layers of pancake, where her own skin colour completely vanished.

While she had some support, the rejection of fair skin as a prerequisite for a model added to the jarring impact Aaminah had. She was only five foot five, which was considered quite short for a model; for an industry in its infancy, not many were happy about the radical changes she brought. But it spurred her on and like a rebel, not only did she continue to shatter perceptions but also set new precedents.

One major one consisted of not viewing modelling as a mere job but in fact, becoming the model. This involved adopting the role the shoot required and not just putting on ‘a shaadi ka jora, sitting there and batting your eyelids’. She was introduced to Tapu and the two of them become best friends and produced work that remains unmatched in content and quality. ‘Tapu never tried to make me into something I wasn’t. The type of shoots we did back then, in a way they were absolutely ground-breaking.’

Transcending the mental block of viewing modelling as a ‘job’, Aaminah was simply wonderful in how she seamlessly morphed into what the concept of the shoot was. ‘I would chop off my hair, sometimes I’d dye it. I looked up to models like Christy Turlington and Linda Evangelista and their careers. That was the kind of editorial work I was interested in doing. I wanted to be able to do a shoot that was timeless.’ Such dramatic chameleon-like changes caused her to be increasingly more in demand, causing her to work with a variety of fashion photographers.

The two-way relationship that Aaminah developed with her photographers was also one of a kind, because it enabled her to have maximum input in the shoot and therefore ‘own’ her work as an individual and a woman, and not just model in it. This stemmed from her firm desire to take responsibility for her own work. ‘You have to look that way, you have to starve yourself so you look a certain way, you have constant maintenance and you have to live that part.’ This led to a whole new standard in the industry, in which the responsibility of the final result of the shoot was also shouldered by the model herself.

This was precisely why, while establishing her work ethic, Aaminah was the first to reject the very newly establiShed modelling agencies that had emerged in Lahore and Karachi. It was a decision that didn’t always go down well but then again Aaminah was not one to be confined. ‘I never bothered with any agency. I was in charge of my career, I never wanted anyone to talk for me. I didn’t want anybody to manoeuvre my life for me, I wasn’t helpless.’

What resulted was that Aaminah retained the freedom to choose what she wanted to wear in a shoot and off the ramp. Whether it was an outfit by Nilofer Shahid or Deepak Perwani, Aaminah and the designer would have an unspoken understanding that a shoot with her wouldn’t just consist of throwing clothes on her and expecting a pretty pose. Aaminah would take over the entire shoot, stylising, conceptualising, and executing it as she pleased.

The same attitude would be adopted when it came to acting in commercials and plays where she rocked the entertainment industry’s boat by setting her own terms. ‘I would read those contracts and make amendments and send them back saying no, this is not acceptable. I am going to tell you how this is going to be and you cannot dictate to me. If I made mistakes, and I made plenty, I was going to own them. If I had to get the blame then that was my blame and if I had to get the credit then it should be mine.’

It is easy to assume that Aaminah must have made enemies in the industry but again with typical style she overcame all of it and set a whole new agenda between models—friendship. While she never expected the models to ‘listen to Joni Mitchell and braid each other’s hair’, what Aaminah did do was bridge the friction between the Karachi and Lahore models. ‘None of the models I worked with had the IQ of a peanut. We were very strong women and we had to fight adversity and society at large. I felt like we were gladiators, I felt like people judged us and maybe it was the camaraderie, but we were in it together.’

By the time the nineties came to an end, the industry was a money making business and Aaminah felt she had plateaued, had lost sense of who she was and was churning out the same kind of work. Once again she carved out a new path, this time with her then partner and now ex-husband, the designer Ammar Belal. With an award for best model under her belt, there was a need to explore new styles of photo shoots

Collaborating with Tapu, she took on projects which stunned in terms of the image she portrayed which was far from the norm that consisted of a pretty face. ‘We said it didn’t have to be pretty, it didn’t have to be traditional. It had to be strong, it had to be sexy. Some pictures had to be non-sexy, cold and challenging.’ Starting at five in the evening, with make up artist Mubasher Khan, the shoot which featured her as a rockstar finished the next day at ten in the morning.q

Another stroke of genius was Ammar Belal’s first campaign. Ammar had asked her to model and Aaminah had taken on the challenge, but even love didn’t get her to compromise. ‘I said I don’t want to be in the backdrop. I said we’re in a relationship and there are people speculating about what we are and who we are. Let’s control that narrative.’ The result? A shoot featuring Ammar and Aaminah together in bed.

It is shocking even by today’s standards how they got away with it, but she points out how things were different pre 9/11 and how rapidly life changed. ‘The world completely changed. I think I was lucky to end my career in 2007 and do what I was able to do and whatever the hell I wanted to do.’

It took an aunt, Ayesha Tammy Haq, to convince her mother to let her do a shoot for Herald and that was all Aaminah needed to get her foot through the door, kick it down and stamp her footprint all over the industry.

But it wasn’t the glamour or the charm of being a model that hooked her initially. ‘I think for me, it was really about becoming more independent, becoming emancipated and choosing a path that was really my own.’ Being the daughter of a landlord, Aaminah struggled with what so many young people hailing from renowned families go through—living under their parents’ shadows.

Having grown up with her maternal family comprising of strong women who decided for themselves in terms of what they wanted to do with their lives, Aaminah’s conscientious decision to model was a means of having a sense of identity and creating her own brand without ever being referred to as somebody’s daughter. ‘I wanted to be Aaminah Haq and I wanted to construct that narrative on my own.’ Little did she know then the rippling waves her decision would send across the then infantile industry and the limitless abyss of creativity she would unleash.

Call it fate or call it luck, Aaminah met people who believed in what she wanted to do and helped her create the supermodel she eventually became. One of them would be Yahsir Waheed, who taught her the crucial things that make a model stand apart from the crowd. ‘When I started modelling, there were very few people who supported what I was doing. So he really helped me create my own stories, my own journey, whom to contact, which magazines to be in. He showed me the kind of model I wanted to be.’

Like-minded independent journalists like Fifi Haroon took notice of this young rebel and a wonderfully creative relationship blossomed. ‘Xtra was a ground-breaking magazine and we still don’t have anything like that today. What Fifi was able to publish and the work she was able to project, it was incredible.’ It was in Fifi that Aaminah would found the same mind-set: a model simply had to be much more than just a coat-hanger and it had to be about ‘embracing who you were’. And when Aaminah met Nabila and Tapu, there was no stopping her.

"By the time the nineties came to an end, the industry was a money making business and Aaminah felt she had plateaued"

By then modelling for her had evolved from seeking an identity to establishing herself as something different as a woman. This was largely because she did not fit the modelling mould that had already been set: tall, lanky. Not that it mattered because she was going to go for everything with a clear goal in mind: to work on her terms.

This caused Aaminah to be one of the first to break an ancient societal rule that had obviously made its way into the modelling industry: Gora rung. ‘I would ask photographers why they were whitening me; that used to be my biggest bone of contention’. This was one major reason why Aaminah found a kindred spirit in Nabila who never tried to mould her into anything else. ‘Nabila really understood me and what I wanted to do, we were very clear about the parameters we wanted to set for ourselves.’

While understanding the need for makeup, Aaminah’s argument was simple—makeup had to be theatrical, it had to make a statement but it most certainly did not have to consist of seven layers of pancake, where her own skin colour completely vanished.

While she had some support, the rejection of fair skin as a prerequisite for a model added to the jarring impact Aaminah had. She was only five foot five, which was considered quite short for a model; for an industry in its infancy, not many were happy about the radical changes she brought. But it spurred her on and like a rebel, not only did she continue to shatter perceptions but also set new precedents.

One major one consisted of not viewing modelling as a mere job but in fact, becoming the model. This involved adopting the role the shoot required and not just putting on ‘a shaadi ka jora, sitting there and batting your eyelids’. She was introduced to Tapu and the two of them become best friends and produced work that remains unmatched in content and quality. ‘Tapu never tried to make me into something I wasn’t. The type of shoots we did back then, in a way they were absolutely ground-breaking.’

Transcending the mental block of viewing modelling as a ‘job’, Aaminah was simply wonderful in how she seamlessly morphed into what the concept of the shoot was. ‘I would chop off my hair, sometimes I’d dye it. I looked up to models like Christy Turlington and Linda Evangelista and their careers. That was the kind of editorial work I was interested in doing. I wanted to be able to do a shoot that was timeless.’ Such dramatic chameleon-like changes caused her to be increasingly more in demand, causing her to work with a variety of fashion photographers.

The two-way relationship that Aaminah developed with her photographers was also one of a kind, because it enabled her to have maximum input in the shoot and therefore ‘own’ her work as an individual and a woman, and not just model in it. This stemmed from her firm desire to take responsibility for her own work. ‘You have to look that way, you have to starve yourself so you look a certain way, you have constant maintenance and you have to live that part.’ This led to a whole new standard in the industry, in which the responsibility of the final result of the shoot was also shouldered by the model herself.

This was precisely why, while establishing her work ethic, Aaminah was the first to reject the very newly establiShed modelling agencies that had emerged in Lahore and Karachi. It was a decision that didn’t always go down well but then again Aaminah was not one to be confined. ‘I never bothered with any agency. I was in charge of my career, I never wanted anyone to talk for me. I didn’t want anybody to manoeuvre my life for me, I wasn’t helpless.’

What resulted was that Aaminah retained the freedom to choose what she wanted to wear in a shoot and off the ramp. Whether it was an outfit by Nilofer Shahid or Deepak Perwani, Aaminah and the designer would have an unspoken understanding that a shoot with her wouldn’t just consist of throwing clothes on her and expecting a pretty pose. Aaminah would take over the entire shoot, stylising, conceptualising, and executing it as she pleased.

The same attitude would be adopted when it came to acting in commercials and plays where she rocked the entertainment industry’s boat by setting her own terms. ‘I would read those contracts and make amendments and send them back saying no, this is not acceptable. I am going to tell you how this is going to be and you cannot dictate to me. If I made mistakes, and I made plenty, I was going to own them. If I had to get the blame then that was my blame and if I had to get the credit then it should be mine.’

It is easy to assume that Aaminah must have made enemies in the industry but again with typical style she overcame all of it and set a whole new agenda between models—friendship. While she never expected the models to ‘listen to Joni Mitchell and braid each other’s hair’, what Aaminah did do was bridge the friction between the Karachi and Lahore models. ‘None of the models I worked with had the IQ of a peanut. We were very strong women and we had to fight adversity and society at large. I felt like we were gladiators, I felt like people judged us and maybe it was the camaraderie, but we were in it together.’

By the time the nineties came to an end, the industry was a money making business and Aaminah felt she had plateaued, had lost sense of who she was and was churning out the same kind of work. Once again she carved out a new path, this time with her then partner and now ex-husband, the designer Ammar Belal. With an award for best model under her belt, there was a need to explore new styles of photo shoots

Collaborating with Tapu, she took on projects which stunned in terms of the image she portrayed which was far from the norm that consisted of a pretty face. ‘We said it didn’t have to be pretty, it didn’t have to be traditional. It had to be strong, it had to be sexy. Some pictures had to be non-sexy, cold and challenging.’ Starting at five in the evening, with make up artist Mubasher Khan, the shoot which featured her as a rockstar finished the next day at ten in the morning.q

Another stroke of genius was Ammar Belal’s first campaign. Ammar had asked her to model and Aaminah had taken on the challenge, but even love didn’t get her to compromise. ‘I said I don’t want to be in the backdrop. I said we’re in a relationship and there are people speculating about what we are and who we are. Let’s control that narrative.’ The result? A shoot featuring Ammar and Aaminah together in bed.

It is shocking even by today’s standards how they got away with it, but she points out how things were different pre 9/11 and how rapidly life changed. ‘The world completely changed. I think I was lucky to end my career in 2007 and do what I was able to do and whatever the hell I wanted to do.’