Generals and Judges are increasingly hogging the headlines with a righteous stream of brotherly, fatherly and elderly (though unsolicited) counsel to politicians, bureaucrats, journalists, etc., on what to write, how to speak or run government, and what not. And why not, they ask, considering the mess which the Civil Representatives of The People have made of the Constitution, elections, democracy, economy, parliament, state and society.

There is a short answer in equal earnest. Generals and Judges have together ruled for almost as long as the Representatives of The People, and historians have awarded both sides less than passing marks on merit. So, what’s new?

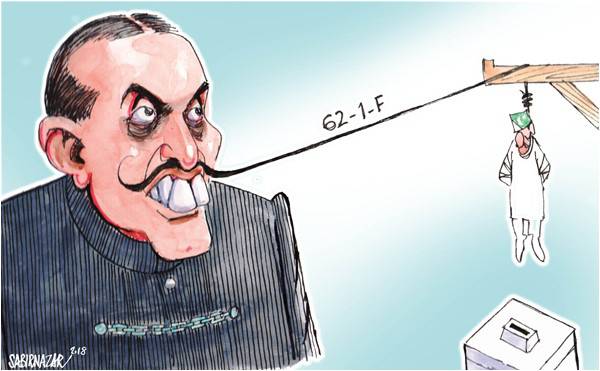

Several things. For one, the “Saviour” complex that was originally rooted in the armed forces for historical reasons in view of the running conflict with India has now infected the judiciary. If the ubiquitous power of the one flows from the barrel of its gun, the supremacy of the other flows from its unaccountability before parliament or Constitution. The judges now appoint and audit themselves, and they set their own principles of interpreting the Constitution and remaking the law. Therefore, they are no longer handmaidens of the government and parliament of the day. Indeed, they are now a veritable Third Force in the pantheon of national power politics. In that sense, the Movement for the Restoration of the Judiciary was a positive turning point for the judges but a negative one for the notion of parliamentary supremacy which is a cornerstone of representative government and democracy. Since then, the judges have sent two elected prime ministers home, one for contempt of court and another for not being a good enough Muslim.

The other new factor is rooted in sociological and demographic developments. Just as the Officers’ Corps of the Pakistan Army of today is recruited from urban middle and lower middle class sections of society as opposed to rural and landed sections of yesteryear, the bar and bench of today also originate in much the same new strata of society, unlike in the past when they too were linked either to the landed elite or to the remnants of the British Raj. This is a post-colonial, urbanizing middle class that is characterized by two impulses: a fierce motivation for upward social and economic mobility on the basis of its education and expertise; and a lurking fear of sliding downwards in a failing economy. Both impulses target “corruption” - (whether in the form of a pervasive sifarshi culture rooted in political affiliations that undermine merit and upward mobility, or economic corruption that denies them goods and services at affordable rates and puts the burden of taxes on them as a salariat - as the bane of their lives. In the early stages of Pakistan’s political and economic development, this class comprised relatively educated and urbanized mohajirs who were also imbued with notions of Islamic nationalism and social equality - hence the support for the Jamaat-e-Islami on the one hand and later for the Pakistan Peoples Party on the other. But, owing to the failure and disillusionment of these options, they now support the PTI on the one hand and militant and extremist religious organisations on the other. Note that the judges, high and low, are loath to summon Imran Khan and hold him accountable because they are also inclined to share his world view, especially regarding corruption.

This “world view” - common to the Officers Corps of the armed forces, bar and bench - is anti-capitalist, anti-feudal, anti-socialist and anti-Western culture. It is also anti-democratic because it perceives western notions of democracy as rooted in feudal and capitalist cultures that are inefficient and rapaciously corrupt.

This analysis suggests two conclusions: one, that the current alliance between the generals and judges is not so much related to the personality of one or two self-righteous judges or generals as it is to a solidifying institutional and class dimension; two, that this dimension is likely to dominate Pakistani politics in the short term until it is jolted out of its Messianic reverie by any one, or a combination, of a number of factors that judges and generals are not trained to cope with or manage. Pakistan’s experience of technocratic or hybrid governments, coalitions and hung parliaments is particularly distressing. On top of it, the country faces hostile neighbours and superpowers which are looking to exploit the lack of stable, long term popular support for the sort of engineered political dispensation that the generals and judges are wont to imagine as the panacea for Pakistan’s myriad and complex problems.

Indeed, we can be sure only of one thing. No number of disappearances and no amount of censorship of the word or image will succeed in this age of information technology. The only factor that will hold nation-states such as Pakistan together is democratic self-determination and decentralization based on a popular national consensus embodied in a sacred constitutional contract. Only visionary and selfless political leaders can provide this, not puppets in masks or Messiahs in uniforms and wigs.

There is a short answer in equal earnest. Generals and Judges have together ruled for almost as long as the Representatives of The People, and historians have awarded both sides less than passing marks on merit. So, what’s new?

Several things. For one, the “Saviour” complex that was originally rooted in the armed forces for historical reasons in view of the running conflict with India has now infected the judiciary. If the ubiquitous power of the one flows from the barrel of its gun, the supremacy of the other flows from its unaccountability before parliament or Constitution. The judges now appoint and audit themselves, and they set their own principles of interpreting the Constitution and remaking the law. Therefore, they are no longer handmaidens of the government and parliament of the day. Indeed, they are now a veritable Third Force in the pantheon of national power politics. In that sense, the Movement for the Restoration of the Judiciary was a positive turning point for the judges but a negative one for the notion of parliamentary supremacy which is a cornerstone of representative government and democracy. Since then, the judges have sent two elected prime ministers home, one for contempt of court and another for not being a good enough Muslim.

The other new factor is rooted in sociological and demographic developments. Just as the Officers’ Corps of the Pakistan Army of today is recruited from urban middle and lower middle class sections of society as opposed to rural and landed sections of yesteryear, the bar and bench of today also originate in much the same new strata of society, unlike in the past when they too were linked either to the landed elite or to the remnants of the British Raj. This is a post-colonial, urbanizing middle class that is characterized by two impulses: a fierce motivation for upward social and economic mobility on the basis of its education and expertise; and a lurking fear of sliding downwards in a failing economy. Both impulses target “corruption” - (whether in the form of a pervasive sifarshi culture rooted in political affiliations that undermine merit and upward mobility, or economic corruption that denies them goods and services at affordable rates and puts the burden of taxes on them as a salariat - as the bane of their lives. In the early stages of Pakistan’s political and economic development, this class comprised relatively educated and urbanized mohajirs who were also imbued with notions of Islamic nationalism and social equality - hence the support for the Jamaat-e-Islami on the one hand and later for the Pakistan Peoples Party on the other. But, owing to the failure and disillusionment of these options, they now support the PTI on the one hand and militant and extremist religious organisations on the other. Note that the judges, high and low, are loath to summon Imran Khan and hold him accountable because they are also inclined to share his world view, especially regarding corruption.

This “world view” - common to the Officers Corps of the armed forces, bar and bench - is anti-capitalist, anti-feudal, anti-socialist and anti-Western culture. It is also anti-democratic because it perceives western notions of democracy as rooted in feudal and capitalist cultures that are inefficient and rapaciously corrupt.

This analysis suggests two conclusions: one, that the current alliance between the generals and judges is not so much related to the personality of one or two self-righteous judges or generals as it is to a solidifying institutional and class dimension; two, that this dimension is likely to dominate Pakistani politics in the short term until it is jolted out of its Messianic reverie by any one, or a combination, of a number of factors that judges and generals are not trained to cope with or manage. Pakistan’s experience of technocratic or hybrid governments, coalitions and hung parliaments is particularly distressing. On top of it, the country faces hostile neighbours and superpowers which are looking to exploit the lack of stable, long term popular support for the sort of engineered political dispensation that the generals and judges are wont to imagine as the panacea for Pakistan’s myriad and complex problems.

Indeed, we can be sure only of one thing. No number of disappearances and no amount of censorship of the word or image will succeed in this age of information technology. The only factor that will hold nation-states such as Pakistan together is democratic self-determination and decentralization based on a popular national consensus embodied in a sacred constitutional contract. Only visionary and selfless political leaders can provide this, not puppets in masks or Messiahs in uniforms and wigs.