Ayubia National Park, once a sanctuary for Pakistan's rich biodiversity and breathtaking landscapes, now faces an imminent threat, as indigenous flora and fauna are battling a grim fate.

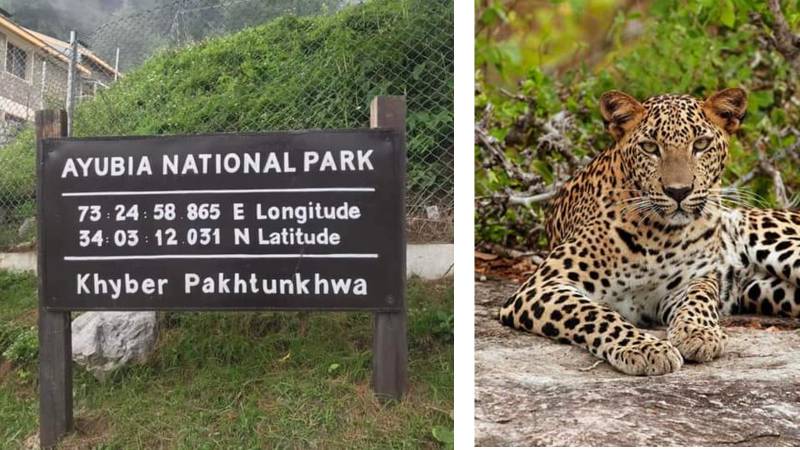

Established in 1984, Ayubia National Park sprawls across 3,300 hectares in the scenic Galiyat region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, its purpose being to safeguard Pakistan's unique natural treasures and protect endangered species, including black bears, wolves, Kashmiri red foxes, golden eagles, and vultures. Yet, the relentless march of human encroachment, with its unchecked deforestation, recurring wildfires and unwelcome intrusion into these hallowed habitats, casts a menacing shadow over Ayubia's exceptional plants and animals.

Once celebrated for serene picnics, invigorating hikes, and lush panoramas, the heart of Galiyat now grapples with gradual decay. Overpopulation, the reach of the timber mafia and the relentless impact of climate change tarnish the charm of this once-paradisiacal retreat. When Rawalpindi and Islamabad swelter in summer's heat, these lofty peaks offer solace – but what was once a lush Eden with rolling hills, babbling streams, pristine rivers, cascading waterfalls, bubbling springs, fertile orchards and bountiful orchards now bears the scars of unchecked human influence.

As the population grows, the vast territories that once featured thriving wildlife shrink at an alarming pace. Housing developments, road networks and commerce not only encroach on wildlife domains but disrupt vital migratory routes, upsetting the fragile ecosystem balance. This encroachment forces wildlife into uncomfortably close contact with human settlements, leading to an increase in human-wildlife conflicts.

Locals and tourists alike now recount heart-pounding encounters with formidable creatures like leopards, bears and monkeys, incidents that lead to substantial property damage and, on occasion, injuries.

Deforestation, wildfires and climate change further exacerbate these conflicts, with leopards, wolves, wild boars and other species venturing into human domains. Shockingly, in the past two years, five leopards have met their untimely demise at the hands of locals, as they can be legally hunted if they pose a threat to human life.

Ghuzanfar Ali, an environmental activist from Galiyat, asserts that rampant deforestation and forest fires bear significant blame for human-wildlife conflicts. He points to photographic evidence that suggests valuable trees have been deliberately set ablaze in and around Ayubia National Park. Shockingly, he claims that authorities may be complicit in this deliberate destruction of trees, as the timber mafia operates openly, mercilessly harvesting precious forests and then systematically incinerating them to erase all traces.

Residents of Galiyat, especially in towns like Nathiagali, Dunga Gali, Changla Gali, Khaira Gali and Khanspur share harrowing tales of encounters with wild animals that have been causing crop destruction and other problems for the local population. Wild boars, for instance, have ventured closer to populated areas, wreaking havoc on homes, livestock and agricultural produce.

Naveed Akram Abbasi, a WWF member and former secretary general of the Abbottabad Press Club, holds the Department of Forests and Wildlife of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government accountable for these threats. He contends that forest fires have compelled wildlife to migrate, leaving rare animals and birds vulnerable to the flames. Carnivores are now forced into regions far removed from the park, where they encounter local residents and, in some tragic instances, endanger human lives. In self-defence, villagers have reported injuries and even fatalities resulting from confrontations with these displaced animals.

Yet, when we approach the wildlife department, a senior officer, speaking on condition of anonymity, reveals a conflict of interest within the various departments at play. He insists that the wildlife department is fulfilling its mission within Ayubia National Park, but that the real threat comes from tourists and certain officials in sister departments who unwittingly disrupting the delicate ecological balance. For instance, well-meaning individuals, whether residents or tourists, feed monkeys along the roadsides, inadvertently altering their natural behaviour. This disruption leads monkeys into human settlements, setting the stage for conflicts between humans and wildlife. This change in behaviour stems from human interference with the food web and food chain in Galiyat.

He suggests instituting educational programs in local schools to raise awareness about wildlife conservation and environmental preservation. He believes that active involvement of local environmentalists and nature enthusiasts can unite efforts to protect the forests.

Civil society activists and environmental organizations have called upon the government to preserve and safeguard the wildlife in Galiyat and its natural beauty. They demand stricter deforestation rules, sustainable forestry practices and action against climate-induced forest fires. Moreover, addressing human-wildlife conflicts, particularly caused by monkey feeding, is vital – and the best way to accomplish this will be through education and habitat protection.