Ringside is an unusual and fascinating book by an erudite and patriotic Pakistani physician. Dr Nasim Ashraf is a graduate of Khyber Medical College and had practiced nephrology in the US. It is an unusual book because it is compiled by someone who was very close to General Pervez Musharraf during his tenure as president. It is fascinating because the book describes in vivid details the palace intrigues that tried to sabotage some of Musharraf’s agenda, including the ambitious plans of the author to implement a nationwide scheme of public health, literacy and volunteerism.

Fate and circumstances took the author back to Pakistan from the US in 2001, when he presented his concept of human development and basic health care in rural Pakistan to the military strongman General Pervez Musharraf. Such fanciful schemes can only be implemented if there is full bureaucratic and political support behind them – and still many schemes fall short and despite noble intentions run into the ground.

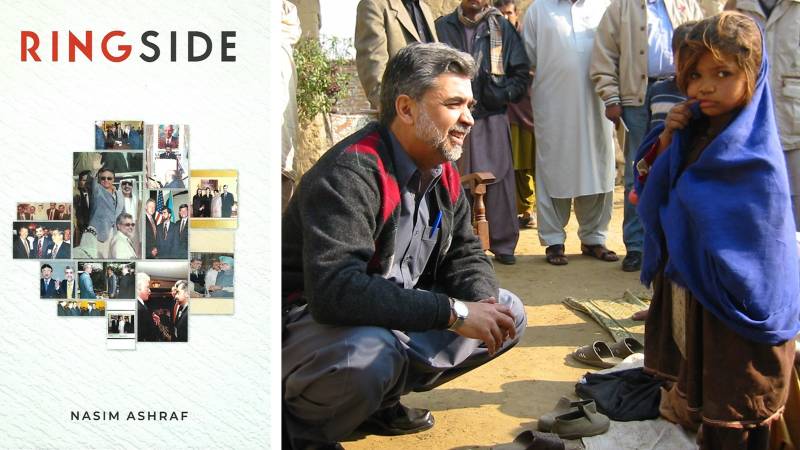

Title: Ringside

Author: Nasim Ashraf

Publishers: Book Corner, Jehlum.

Format: Hard cover. Pp 347

Price: PKR 1,200

Nasim Ashraf served for six years in the cabinet of President General Pervez Musharraf as a minister of state. His sole objective to serve in a non-democratic government was to implement a human development plan in the country. Earlier when was president of the Association of Physicians of Pakistani Decent of North America (APPNA) in 1987, he had conceived of a basic health plan for rural Pakistan. It was tried on a small scale in a handful of districts in Pakistan and was extremely successful. The scheme was also recognised at the international level.

General Musharraf asked him to implement the scheme he had presented to the top brass earlier.

The establishment of a National Commission for Human Development (NCHD) and Dr Ashraf’s appointment as its chairman with the status of minister of state was the culmination of his dream to do something substantial for the poor people of Pakistan. Along the way, he also served as chairman of Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) for two years.

Within few years of NCHD’s establishment, its presence was felt across the country. In a short span of six years, it achieved increased literacy rates, enrolled nine million out-of-school children, opened 10,000 community-based primary schools in remote areas of the country and recruited 20,000 teachers for those schools. Along came increased immunisation, and training of housewives to prepare life-saving oral rehydration solution resulting in 30% reduction in infant mortality.

To carry out the objectives of the Commission, Dr Ashraf recruited the best and brightest Pakistani graduates of American Ivy League universities.

NCHD also provided internship opportunities for young men and women to connect with the grassroots in Pakistan and help improve their lot. One such young man was Nicholas Blair, the son of British prime minister Tony Blair, who spent three months living with other interns in primitive conditions and eating simple Pakistani meals.

Not many people know that for eight years he put his professional and family life on hold and worked diligently to make a difference in the lives of people in rural areas of Pakistan. And all that without accepting any salary or monetary compensation from the government

Dr Ashraf’s influence with the high echelons in US government came handy for Musharraf’s government. In 1999, US president Bill Clinton was to visit India but Pakistan was not on the itinerary. It took some direct and indirect pressure to add Pakistan to President Clinton’s itinerary. The American president wanted assurances that Musharraf would not hang the deposed prime minister Nawaz Sharif. He was assured that it will not happen. However, even when Clinton decided to make a brief stop in Pakistan, he was not sure of Musharraf’s intentions.

During a lunch meeting at the President House in Islamabad, Mr Clinton excused himself and headed to the lavatory. Soon the Chief Justice of Pakistan Mr Irshad Hasan Khan also walked towards the lavatory, raising eyebrows and eliciting smiles. It was an amusing coincidence to have two important people have a simultaneous call of nature. I guess President Clinton wanted further assurance from the chief justice that Nawaz Sharif would not be hanged after a sham trial.

In 2008, President Musharraf under political pressure resigned. Within hours of his resignation, Nasim Ashraf also resigned from the government.

Not many people know that for eight years he put his professional and family life on hold and worked diligently to make a difference in the lives of people in rural areas of Pakistan. And all that without accepting any salary or monetary compensation from the government. Since his departure from the government the National Commission for Human Development has survived the test of time and is still functioning.

In this book, Dr Ashraf has chronicled the events that unfolded in Pakistan and abroad. He saw unfolding dramas, palace intrigues, and noble deeds from a ringside seat. President Musharraf depended on Dr Ashraf’s first-hand knowledge of American government and then current political realities in Washington. Hence, he was included in meetings dealing with foreign affairs, particularly US president and other high government officials in Washington.

His vivid description of the visits to the White House, Camp David (the presidential retreat in the mountains of Maryland), and sitting in meetings with high US officials gives us insights into behind-the-scenes conversations and deliberations.

Nasim Ashraf is in so many ways like Norman Borlaug, the American crop scientist who introduced high-yield grain crops in Mexico and later in India, Pakistan, and Africa and ushered in the Green Revolution. Or like Muhammad Yunus, the founder of the microcredit scheme in Bangladesh that revolutionised the concept of lending small amount of money to the poor. Nasim Ashraf has done what others had tried in the past with lofty schemes but failed. His work has been duplicated in the third world countries.

Decades before joining the Pakistani government, he had helped complete the movie Jinnah, a film on the life of the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He had also founded Peace and Justice organisation to further the cause of Pakistan in the West. Most of his work is chronicled in the book. Though he conceived and spearheaded many projects he is the first to give credit to those who helped him in those efforts.

Other chapters in the book are equally interesting and intriguing; “War on Terror,” “Pakistani Diaspora,” “US-Pakistan Relations,” and “Why America could not win in Afghanistan.”

The author must be forgiven for appearing to be under the spell of General Musharraf and praising him lavishly. But seen from the vantage of Dr Ashraf, it was General Musharraf who bought the idea of human development and supported it despite some naysayers in his inner circle, not to mention the powerful federal bureaucracy.

The book has some minor flaws. There is no index at the end of the book. The historic photographs are reproduced in rather small ‘postage stamp’ size. But these minor flaws do not take away from the compelling narrative.

As the present recedes so imperceptibly into the past, it leaves in its wake valuable lessons. Unless we record and understand the present and the past, we cannot chart a coherent course for the future. By recording in some detail an eventful era in Pakistan’s history, Dr Nasim Ashraf has done a great favour to the present and future of the country.