Pakistan’s roller-coaster performance and projections on economic growth and development have roused considerable scholarly, policy community, journalistic, and practitioner interest. To mention a few, Akbar Zaidi, Rashid Amjad, Omar Noman, Shahid Kardar, and Akmal Hussain in their extensive studies on Pakistan‘s political economy have addressed, the challenges, choices, and pitfalls of Pakistan’s development quondam. Each also proposed corrective measures, which have been largely ignored or half-heartedly accepted by the military and civilian regimes of the country. In the 1980s Lawrence Ziring declared Pakistan an ‘Enigma of Development’—and today, low economic development, explosive population growth, erosion of civic virtues, and civility continue to haunt Pakistan and its enigmatic despondency reigns supreme. Over the past four to five decades proliferation of development challenges confronting Pakistan has attracted several scholars, and policy analysts and given a boost to studies on development. For example, in 2011, Anita Wise and Saba Khattak(ed) published a book that carried articles by 13 national and international scholars, titled, Pakistan: Challenges of Development. Asim Sajjad Akhtar, The Politics of Common Sense: State, Society and Culture in Pakistan (2018), provides a critical appraisal of development challenges from a Neo-Marxian perspective.

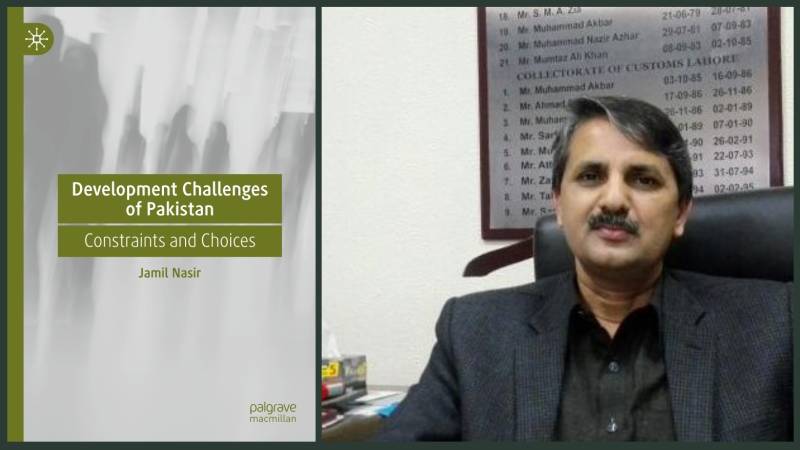

In short, the topic has been researched largely from economic and political perspectives, yet the lack of development continues to entice scholars and observers of Pakistan to seek to explain the dynamics of development challenges confronting Pakistan. In this context Jamil Nasir’s book, Development Challenges of Pakistan: Constraints and Choices (2024) is yet another manifestation of that search and inquisitiveness. Jamil Nasir’s research is refreshing, innovative, and provocative in several ways.

The book has five outstanding features. First, it is conceptually, theoretically & methodologically rigorous. Differentiates between sustainable development and economic growth and provides deep insights into the varied structural problems and their changing dynamics, sources, and documents. Second, it cuts across disciplinary boundaries and the author has skillfully used literature from Economics, Anthropology, Sociology, and Political Science to identify and analyse the developmental challenges that confront Pakistan-- from poverty and bureaucratic inertia to mental health. Third, while providing a scathing critique of Pakistan’s development policies, practices, and the role of bureaucracy, the author also highlights the policy choices that Pakistan could have made, providing insights as an insider, who was either involved or saw governmental policy decision making from a close angle. This helps him share the experiences of other countries from the Global South with similar circumstances, such as India, Korea, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Fourth, the book sneaks into an attention-grabbing insider account as Nasir not only shows the dedication of a scholar but also reveals the additional advantage of a practitioner.

Developmentalists and Economists invariably do not concern themselves with culture and other non-economic factors, but it is both of these that contribute to a country’s development

As a civil servant (Customs Service) with ample national and international exposure, the author tries to synchronise the two by offering a candid and forthright analysis of the multiple inequalities and uncovers the causes of the absence of a culture of growth in Pakistan; attributes it to rooted in the obsolete educational system, regressive teaching of religious studies that contribute towards attitudes of fatalism, backwardness, rather than approaching problem resolution, rational and forward-thinking attitudes. He propounds beliefs, norms, attitudes, and outlook towards life matters in development. Developmentalists and Economists invariably do not concern themselves with culture and other non-economic factors, but it is both of these that contribute to a country’s development, which makes this research distinctively different and significant and could pave the way for further research on the subject. Finally, the book is reader-friendly and the chapterisation is systematic, absorbing, perceptive, and avoids academic jargon. The book is divided into fifteen chapters, including the conclusion. Each chapter focuses on a specific challenge, such as inequality, rural growth, poverty, and militancy. In my view, chapters 3 Culture and Growth, 4, the question of education, 5, Health, 10, on the public sector, 12, on social capital & corruption are must read to understand the key arguments of the author and that are interwoven.

The book is voluminous (622 pages) and of course, a few chapters could have avoided historical details and description. For a book, this size striking a balance between academic rigor and, the necessities of literature review and still keeping it engaging and readable is a difficult task and Nasir Jamil has done a commendable job in keeping it analytical and reader-friendly. The fundamental theme and analysis of the book revolves around a conscious picking question; ‘why is Pakistan not on a sustainable trajectory of economic growth?’ To untangle the socio-economic and politico-cultural complexities surrounding it, Nasir produces an extensively researched and evidence-based response.

If we want to have a deeper understanding of the developmental issues in a state, other than economics we must also consider factors like the geography of the region, institutions of the state which ensure the rule of law, and culture of the state

He takes a Structuralist position and contends, ‘Economic growth is a complex process which is embedded in the socio-economic and political struck-tures of the society. He continues, ‘non-economic factors and variables like culture, institutions, patience, political stability, eagerness to welcome new ideas, and quality of leadership are also its important determinants’. Nasir argues that Pakistan saw periods of economic growth during the 1960’s through the 1980s, it saw a slowing down in the 1990s and he attributes it to non-economic factors, such as quality of leadership, political instability, and more importantly increased reliance on IMF programs and conditionalities. For instance, during the 1960s, despite having the same indicators as South Korea and the Philippines, land reforms in Pakistan were not able to achieve the same effect as the other two countries because the reforms that were proposed were done half-heartedly. Similarly, during the ‘Green Revolution’ in Pakistan, the importance of a rural non-farming economy was emphasised but the initiatives taken to boost it did not trickle down to the landless peasantry.

So, what went wrong despite having reasonable growth in its early years? He responds economic growth is not sustainable in the long term if people are alienated from the process. If we want to have a deeper understanding of the developmental issues in a state, other than economics we must also consider factors like the geography of the region, institutions of the state which ensure the rule of law, and culture of the state; is it forward-looking or backward-looking in terms of embracing innovations and virtuousness of technology. For fostering economic growth, a future-oriented mind set is a prerequisite. In the Pakistani case, the education system and culture hamper a forward-looking mentality. He is critical of cultural constraints that make Pakistan backward-looking but shies away from proposing cultural reform that could change the dynamics of the power structure, whereby redistribution of power from the privileged few to a larger portion happens. However, the author is vigorous in making a case for investment in youth and human capital.

He points out that in Pakistan growth has suffered because of low investment in human capital, inequitable distribution of production assets, and weak governance capacities. Therefore, his central argument and recommendation is, ‘that sustainable growth without prioritising human resource development and pro-people policies for a longer period is not possible’. The human factor is important for productivity, socio-political stability, and innovation which are important inputs for economic growth. Growth and development go hand in hand. An equitable growth that is embedded in development and would benefit most if not all the citizens. Reflecting on economic growth and poverty, Nasir vies that poverty cannot be elevated through just microfinance and cash transferring schemes, he points out that such schemes only help boost consumption but do not end poverty cycles. For sustainable growth economic reforms are essential. Sharing his reflections on reforms he persuasively argues that in content and orientation, reforms are incremental. Reforms require patience, decades of planning, and commitment, one can’t expect change to occur overnight. These reforms could be challenging but for a better and sustainable future, he puts the onus on the government which must pursue such reforms: (1) distribute state-owned land, (2) provide small-scale credits with lower interest rates, (3) increase wealth and inheritance tax and it must ensure financial inclusion of all genders. (4) the government needs to focus on Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). (5) Starting small farm initiatives can ensure that people are given a share in the pie and can improve the quality of production too.

Analysing public sector functions and performance, Jamil Nasir shows how governance and state capacity& multiple factors analysed in each chapter impede development in Pakistan. For instance, rampant corruption leads to a sense of scarcity and promotes a culture of clientelism, trust in institutions is largely deficient, rampant tax evasion is another factor that not only hinders growth but also puts an unnecessary burden on an already fragile economy, relationships with neighboring countries are precarious due to militancy, resulting in loss of trading opportunities. Implicitly he makes a case for opening up trade with India to move away from a culture of militancy to a culture of regional connectivity, trade, and peace that leads to sustainable development. To enhance the capacity of state institutions, he postulates technology-driven training of public servants, inculcation of compassion, ethical values, and a zest for public service. He calls for staying away from multilateral donor reforms and reliance on local expertise that gels with local needs and the environment. Combining these with enhancing provincial autonomy and local community and government empowerment.

Besides academia, post-graduate students, media, and researchers, the book would be a useful resource for the Training institutions of bureaucracy both federal and provincial, judicial academies, military & NGOs’ (National & international) working on Pakistan’s policy-making, sustainable development, and a must read for politicians.