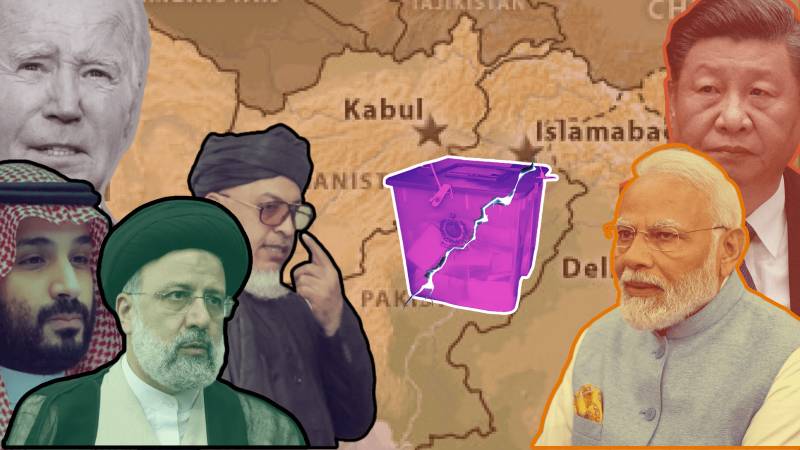

The controversial general elections of February 8, 2024, have deepened political divisions in the country. Increased polarisation, conflicting claims and street agitations, seen together with an almost-collapsed economy, create extreme uncertainty. What could this mean for Pakistan's foreign policy requires careful assessment.

Looking at the current global environment, we see the conflict in Gaza becoming one of the most important influencers of international relations. The conflict has very real implications for domestic politics everywhere, but more so in Muslim countries. Mostly, religious forces are taking the lead in framing the Gaza conflict, framing it as a conflict between Muslims and Jews rather than an issue of people's rights versus settler colonialism. This is further augmented by the attitude adopted by those who are pro-Israel in the West, who frame the pro-Palestinian and pro-peace voices as either Islamic fundamentalist and/or antisemitic. If we limit ourselves to Pakistan, the conflict is fueling existing intolerance on both the religious and ethnic fronts.

The US-China rivalry/ competition is also on the rise. The pressure on Pakistan to take a side has increased manifold. Pakistan's fragmented polity, exacerbated by contentious elections and a weakening, cash-hungry economy, makes it very hard to resist these external pressures and pursue an independent foreign policy or stand on one side or the other.

Internationally, for the West, the priority has shifted to the Middle East. Irrespective of how Islamabad feels, the West does not feel it has enough stakes in Pakistan to bail it out of its latest conundrum. On the other hand, China is being very careful. While it is not ready to give up on Pakistan, it is unable to ignore the volatile and uncertain situation of Islamabad and offer help. Saudi Arabia has promised some investment, but it is also watching which way the wind blows. It expects a lot in return for its investment.

In the region, Pakistan and Iran were able to contain the fallout from recent cross-border intrusions, accusations, and counter accusations. Nevertheless, the two neighbours are now more suspicious of each other. Afghanistan, under the Taliban, is becoming even more — or at least as — hostile than at any moment in the recent past. The issue of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the forced expulsion of Afghans and the recent statement from Afghanistan's Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Stanikzai on the Durand Line further adds to the tensions in Pakistan-Afghanistan relations.

In our current environment, debates on foreign affairs, security, or even economic policy are absent, save for a few faint voices. Mainstream political contenders have failed to present alternate visions in any policy area

On the eastern border, India is poised to re-elect Narendra Modi as prime minister for another term. It is not willing to ease tensions, even if Pakistan wants.

The election controversy may have pushed foreign policy debates to the back burner, but it has not done away with their challenges. Not only do these challenges exist, but they have intensified in certain cases, and the impulse to change and adapt has decreased. The absence of any impulse to consciously debate, think over and plan changes does not mean policies will continue as they have. Rather, they may result in unplanned changes forced by a changing environment. Enemies may find this as an opportune moment to take advantage, while our friends may be worried and unsure whether to continue banking on Pakistan's ability to return favours or to start looking elsewhere.

In this regional, as well as global environment, political instability and an economic meltdown may push up religious and ethnic violent extremism, thus enhancing existing terrorist threats. One can expect that the current phase of resurgent terrorism and violence will not stay confined to the peripheries. Terrorism, which crosses the domestic and foreign domains, needs no elaboration.

Hard times require hard decisions, but hard times make taking hard decisions very difficult. To make hard decisions that change course, you need an intellectual understanding, as well as political will, stability, and economic health. For Pakistan, all four are currently missing.

In our current environment, debates on foreign affairs, security, or even economic policy are absent, save for a few faint voices. Mainstream political contenders have failed to present alternate visions in any policy area, whether in the foreign or domestic domains. Instead, the debates have been about proving their capability and loyalty to existing policies, not any alternatives.

On the economy, all sides are basically arguing neo-liberal formulas. While everyone talks of austerity, no one talks about austerity in defence spending. There is little difference in the mainstream when debating the political, academic or state structures. A similar approach is taken towards national security issues, China, USA, Saudi Arabia, India, Afghanistan or any other aspect of foreign or security policies. The mainstream intelligentsia appears loyal to the pre-dominant, pre-existing, security-centric and unitary narrative. Pakistan has no dearth of human capital, with good, competent people in mainstream academia or in other fields, too, but the undemocratic decision-making system that has evolved does not offer any space to entertain a different opinion.

There is still a rare chance that the mainstream intelligentsia, including academia but not limited to it, creates space for alternate voices. They resist the populist temptations and argue on issues rather than becoming part of the partisan point-scoring or turn apologists over the state narrative

The controversial elections have furthered this absence of debates. This is not to argue that there should not have been any elections, which would have been even worse. Yes, if they were held freely and fairly and were considered credible by all, they may have put Pakistan on the path of recovery. But the fact is, they have not been and cannot now be undone. A few calls for new, free and fair elections or meeting all stakeholders to find a peaceful and democratic way out of the mess, are good and well-intentioned. However, the level of mistrust, polarisation, and, very importantly, intellectual poverty has reached a stage where such advice will not see the light of day.

This write-up consciously avoids presenting any alternative policies or concrete steps to bring about change, as they would be just a wish list, without reflecting any change in decision-making to have space for and a culture of encouraging alternate thinking and discourse. The political parties can start by having detailed policy papers on foreign and security policies, unlike the current rhetorical statements on Kashmir and the Ummah.

So, is all lost? It appears to be. However, there is still a rare chance that the mainstream intelligentsia, including academia but not limited to it, creates space for alternate voices. They resist the populist temptations and argue on issues rather than becoming part of the partisan point-scoring or turn apologists over the state narrative.

This will be a slow and gradual road to a peaceful, prosperous state and society. As the Chinese say: 'The journey of a thousand miles starts with the first step'. A change in the dominant state-centric, unitary narrative is required. Narratives can create perceptions and attitudes which educate and determine policy choices. The only path to such a change is an impersonal, educated debate with space for peripheral voices.

Admittedly, this is a long, slow process to correction, which, unfortunately, provides the only way out.

Some may argue that it is too late to take this road. Such an argument carries some strength. But if it is believed, then only destruction lies ahead. The immediate decision in foreign policy is to end any grandstanding and to desist from trying to control other states. Policies based on the use of religion as a tool and the belief in being of significance to others due to its unique geostrategic location have to be given up. One has created and will create even more domestic challenges than gains, while the other is no longer enough to push other states to pay your bills.

Those groomed into believing, promoting and benefitting from dominant narratives and their resultant policies cannot just wish to correct themselves through well-meaning appeals or well-developed arguments alone. However, amidst all the chaos and mayhem, the weakening controls of the controllers and lack of any democratic alternative may open up space for alternate voices to be heard and pushed towards change with dominant narratives and policies.