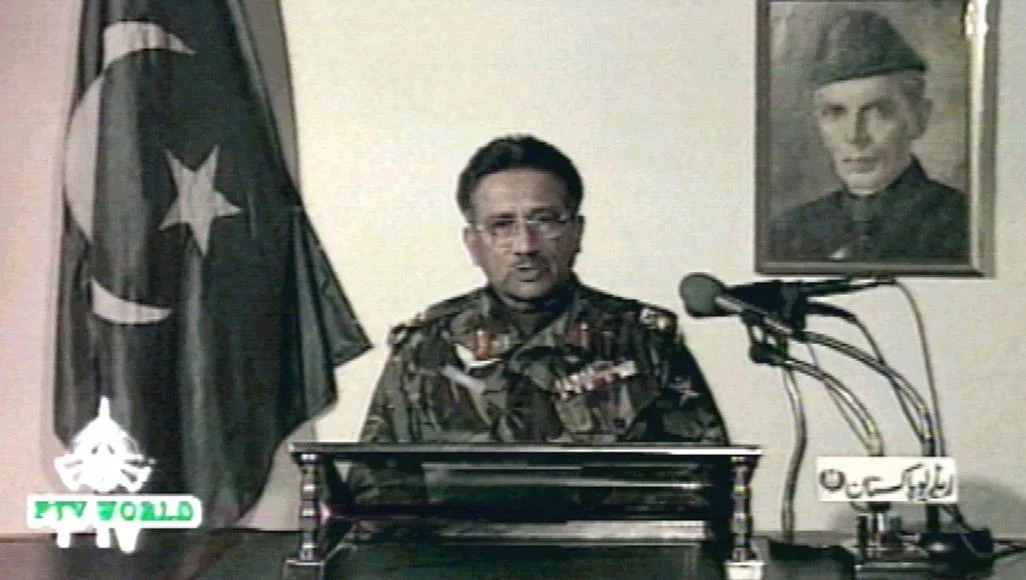

It was around 4:30 pm on 8th October 1999. I got a call from my father, ‘the story is over, don’t go anywhere,’ he said, and hung up. He worked in an Urdu newspaper, and he got the news of General Musharaf’s coup quite early, well before it was announced in the wee hours of the night on PTV – the only TV channel in those days. The next day’s newspapers featured the images of army personnel taking control of important government buildings, including PTV. In 1977, I was quite young, but I can still recall the night when General Zia-ul Haq imposed martial law. I heard someone saying that curfew had been imposed. I was happy because there was no school next morning. Later in the evening, a photographer came to take picture of my father for making a curfew pass for him – back then, he used to read the 9:00 pm news bulletin on PTV. It all looked quite exciting and thespian - almost the same as the 1999 coup – very typical. But those exciting days are, perhaps, now a matter of the past.

In How Democracy Ends, David Runciman provides an explication of rather more modern, more creative and non-militaristic ways to end democracy. These sophisticated methods, however, are not as exciting and dramatic as the ones we have experienced in the past – curfews, tanks rolling on the streets, military men jumping over the gates of PTV, followed by a great speech starting with ‘My dear countrymen…’ Following Runciman’s methods, you don’t need an army general to end democracy, the civilians can do it themselves by following five creative, subtle, and rather painful ways.

For instance, the civilians can stage an ‘executive coup’, when those already in power suspend democratic institutions; or they can manage ‘election-day vote fraud,’ by fixing the electoral process for producing the results of their own choice. Another way of undermining democracy is a ‘promissory coup’ – this can happen when people in power hold elections to legitimate their rule – e.g., a referendum. Or those in power can try ‘executive aggrandizement,’ by chipping away democratic institutions without ever overturning them. One may undermine democracy by exercising the all-time favorite - ‘strategic election manipulation.’ In this type of coup, elections fall short of being free and fair, but a good face of democracy is, nevertheless, maintained.

Many of these methods have been tried and tested successfully in Pakistan. But, why is Pakistan so vulnerable to coups? To be able to understand this, we need to be clear on one point – politics is tied to the state of the economy. When in a democratic country, the economy doesn’t perform well, then democracy is in jeopardy. This deficiency creates a vacuum that sucks in other forces. When General Zia-ul-Haq took over in 1977, the GDP growth rate was 3.95% - in 1978 it went up to 8.05%. In 1998, shortly before General Musharaf took over, the GDP growth rate was 2.55%, and 5 years later in 2004, it went up to 7.55%. In the recent years, the standard of living in Pakistan has drastically gone down - the per capita income has fallen from $1,765 to $1,568 in the previous year alone. Food inflation is insanely high at 37.9% - meaning that most people can barely afford to buy food. Runciman concludes that a country with per capita income with less than $4,000 is prone to coups – military or civilian. Democracy can end if the economy performs poorly.

A vital sign of a democracy functioning well in a country is when a smooth transfer of power has been taking place over a considerable period. A good electoral process guarantees the life of democracy –elections are held on time, the votes are cast peacefully, and the losing party open-heartedly accepts the outcome of the elections. If the losing party refuses to accept the results, takes to the streets – as it happened in 2013, when PTI refused to accept the election results – rightly or wrongly - democracy tumbles down. Street politics and agitation render two things: political instability and bad law and order situation – both are fatal for the economy. And when the economy goes down, democracy tumbles down with it.

Another serious dent in the democratic system in present day Pakistan is the tug-of-war between various democratic institutions: the Parliament, executive and the top judiciary. In recent years, it has emerged as a very unsettling problem compared to the past, when despite all disagreements and dislikes, key institutions maintained their mutual balance of power. Starting from the restoration of the National Assembly – dissolved by President Ghulam Ishaq Khan in 1993 - by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, and later the ouster of Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gillani by the Supreme Court in 2012, the Constitution and the decisions of the apex court were upheld, no matter how controversial or undesirable they may have been.

This tradition, however, is a matter of the past. The very question arising pertaining to the powers and the authority of the Supreme Court, and those of the Parliament and the Executive, are a serious blow to democracy. In addition, violation of the Constitution, by not holding the elections of the Punjab and PK Assemblies within the prescribed period by the constitution, is fatal. This, in Runciman’s terms, is a combination of an executive coup and executive aggrandizement. This neatly ends democracy without any military intervention. And if the military decides to take over in the wake of all this, they have sufficient grounds to justify their action – the Constitution has been violated, democratic institutions have been pitched against each other, and hence democracy has ceased to function, virtually. And here we stand!

Robert Frost wrote:

In How Democracy Ends, David Runciman provides an explication of rather more modern, more creative and non-militaristic ways to end democracy. These sophisticated methods, however, are not as exciting and dramatic as the ones we have experienced in the past – curfews, tanks rolling on the streets, military men jumping over the gates of PTV, followed by a great speech starting with ‘My dear countrymen…’ Following Runciman’s methods, you don’t need an army general to end democracy, the civilians can do it themselves by following five creative, subtle, and rather painful ways.

For instance, the civilians can stage an ‘executive coup’, when those already in power suspend democratic institutions; or they can manage ‘election-day vote fraud,’ by fixing the electoral process for producing the results of their own choice. Another way of undermining democracy is a ‘promissory coup’ – this can happen when people in power hold elections to legitimate their rule – e.g., a referendum. Or those in power can try ‘executive aggrandizement,’ by chipping away democratic institutions without ever overturning them. One may undermine democracy by exercising the all-time favorite - ‘strategic election manipulation.’ In this type of coup, elections fall short of being free and fair, but a good face of democracy is, nevertheless, maintained.

Many of these methods have been tried and tested successfully in Pakistan. But, why is Pakistan so vulnerable to coups? To be able to understand this, we need to be clear on one point – politics is tied to the state of the economy. When in a democratic country, the economy doesn’t perform well, then democracy is in jeopardy. This deficiency creates a vacuum that sucks in other forces. When General Zia-ul-Haq took over in 1977, the GDP growth rate was 3.95% - in 1978 it went up to 8.05%. In 1998, shortly before General Musharaf took over, the GDP growth rate was 2.55%, and 5 years later in 2004, it went up to 7.55%. In the recent years, the standard of living in Pakistan has drastically gone down - the per capita income has fallen from $1,765 to $1,568 in the previous year alone. Food inflation is insanely high at 37.9% - meaning that most people can barely afford to buy food. Runciman concludes that a country with per capita income with less than $4,000 is prone to coups – military or civilian. Democracy can end if the economy performs poorly.

A vital sign of a democracy functioning well in a country is when a smooth transfer of power has been taking place over a considerable period. A good electoral process guarantees the life of democracy –elections are held on time, the votes are cast peacefully, and the losing party open-heartedly accepts the outcome of the elections. If the losing party refuses to accept the results, takes to the streets – as it happened in 2013, when PTI refused to accept the election results – rightly or wrongly - democracy tumbles down. Street politics and agitation render two things: political instability and bad law and order situation – both are fatal for the economy. And when the economy goes down, democracy tumbles down with it.

Another serious dent in the democratic system in present day Pakistan is the tug-of-war between various democratic institutions: the Parliament, executive and the top judiciary. In recent years, it has emerged as a very unsettling problem compared to the past, when despite all disagreements and dislikes, key institutions maintained their mutual balance of power. Starting from the restoration of the National Assembly – dissolved by President Ghulam Ishaq Khan in 1993 - by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, and later the ouster of Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gillani by the Supreme Court in 2012, the Constitution and the decisions of the apex court were upheld, no matter how controversial or undesirable they may have been.

This tradition, however, is a matter of the past. The very question arising pertaining to the powers and the authority of the Supreme Court, and those of the Parliament and the Executive, are a serious blow to democracy. In addition, violation of the Constitution, by not holding the elections of the Punjab and PK Assemblies within the prescribed period by the constitution, is fatal. This, in Runciman’s terms, is a combination of an executive coup and executive aggrandizement. This neatly ends democracy without any military intervention. And if the military decides to take over in the wake of all this, they have sufficient grounds to justify their action – the Constitution has been violated, democratic institutions have been pitched against each other, and hence democracy has ceased to function, virtually. And here we stand!

Robert Frost wrote:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.