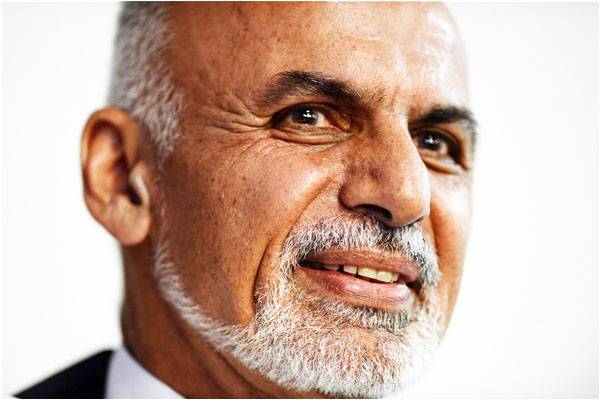

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani came to power in September 2014. His presidency was welcomed not only by the Afghans, but also by the United States and Pakistan – the two countries with a considerable stake in the future of Afghanistan. Washington had found his predecessor Hamid Karzai to be ‘unreliable’, and his well-known anti Pakistan rhetoric had not gone down too well with Islamabad either.

In the early days of the Ghani presidency, there was a fundamental positive shift in Kabul’s policy with Islamabad. There was none of the Karzai era finger pointing at Pakistan. Instead, there were peace overtures, of combined futures, shared cultures and prosperity. The change of heart was because of one of Ashraf Ghani’s key electoral promises: delivering peace to Afghanistan. That meant peace talks with the Afghan Taliban, which in turn meant Pakistan.

As one analyst put it back then, “He’s put all his eggs in the Pakistani basket, I’m not so sure if that’s a great idea.”

Fast forward 15 months, and things could not be more different. Instead of curtailing Taliban advances, according to the Long War Journal, the nationalist jihadi group now controls at least 20% of the country with a large presence in a much greater area. Pakistan, for its part, has been unable to fulfill its promise of getting the Afghan Taliban on the negotiating table.

President Ashraf Ghani finds himself under serious pressure at home. Addressing a rare joint session of the two houses of the Afghan Parliament, Ghani said: “We do not expect Pakistan to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table.” This resignation, by the Afghan president, takes on a wholly different meaning when seen in the light of the recent admission by Sartaj Aziz, advisor to the prime minister on foreign affairs, that the afghan Taliban’s leadership is in Pakistan.

And according to Sami Yousafzai, Newsweek’s correspondent for Pakistan, “If they’re using the hospitals, as pointed out by Sartaj Aziz, they’re also using the territory.” This fact, Yousafzai feels, has created unbelievable amounts of bad blood for Pakistan. “The Afghans now think that all the violence they’ve had to face over the last fifteen years, it’s all come from the other side of border.”

This creates an uneasy situation for President Ghani, who finds himself stuck between an enemy within his borders and an ally unwilling to play its part. What, then, can he do?

He could go to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), but it is highly unlikely that any of the full members will support him, says Yousafzai. And even if he was to get some form of backing, it would further antagonize an already shaky relationship with Pakistan. With options limited, Kabul has turned to Washington to play its part in getting Islamabad on track.

A scathing editorial by the New York Times titled ‘Time to put the Squeeze on Pakistan’, repeats what most of the western press has been saying for some time now: the key to peace in Afghanistan is Pakistan, and it’s not playing ball. There is also the no small matter of the Haqqani network as well, with both Washington and Kabul alleging that Siraj and co are now at the operational heart of the Taliban insurgency. It has long been alleged that the Haqqanis have close ties with the Pakistani establishment.

Afghanistan is now looking to have the Taliban declared ‘irreconcilable’ and pushing for military action against the group. Regardless of the outcome of the meeting of the Quadrilateral Coordination Committee (QCG), Pakistan will be hard pressed to take action against the Afghan Taliban within its borders, primarily for two reasons. The first is the extent to which Pakistan can influence the Afghan Taliban. As a former diplomat told me, “Even if we get them to the table, we can’t control the conversation.” And the second is the possibility of a violent backlash inside Pakistan. Over the past year, the country has made hard fought gains against terrorists holed up in the tribal regions. A long awaited limited operation has also gotten underway in the Punjab.

“To open up a new front, or even the possibility of a new front, at this time is inconceivable,” an intelligence officer admitted.

With Kabul and Islamabad at loggerheads about the way forward with the Taliban, it may fall to the other two members of the QCG, Beijing and Washington, to resolve the stalemate. Clearly, the United States will be looking for some semblance of peace in Afghanistan so that it may withdraw from the country with some respectability intact. However, given the recent slide in relations between the two countries, China seems to be best bet, with big projects planned not only in Pakistan, but Afghanistan as well. As Barnett Rubin, a leading expert on the region said at last year’s Lahore Literary Festival, “the economics of the region demand stability.”

It is under these vexing circumstances that the chiefs of the Pakistani and Chinese militaries have met very recently in Beijing, ostensibly to discuss the CPEC. “I’m certain the situation in Afghanistan will have also been discussed,” says journalist and author Ahmed Rashid. “The problem however is that for all intents and purposes, there has been no shift in policy on Pakistan’s side vis-a-vis the Afghan Taliban,” he argues.

With things remaining as they are, President Ashraf Ghani may find himself banging his head against a brick wall, unable to deliver peace to his people. What this will do to his presidency is anybody’s guess.

In the early days of the Ghani presidency, there was a fundamental positive shift in Kabul’s policy with Islamabad. There was none of the Karzai era finger pointing at Pakistan. Instead, there were peace overtures, of combined futures, shared cultures and prosperity. The change of heart was because of one of Ashraf Ghani’s key electoral promises: delivering peace to Afghanistan. That meant peace talks with the Afghan Taliban, which in turn meant Pakistan.

As one analyst put it back then, “He’s put all his eggs in the Pakistani basket, I’m not so sure if that’s a great idea.”

Fast forward 15 months, and things could not be more different. Instead of curtailing Taliban advances, according to the Long War Journal, the nationalist jihadi group now controls at least 20% of the country with a large presence in a much greater area. Pakistan, for its part, has been unable to fulfill its promise of getting the Afghan Taliban on the negotiating table.

"He's put all his eggs in the Pakistani basket"

President Ashraf Ghani finds himself under serious pressure at home. Addressing a rare joint session of the two houses of the Afghan Parliament, Ghani said: “We do not expect Pakistan to bring the Taliban to the negotiating table.” This resignation, by the Afghan president, takes on a wholly different meaning when seen in the light of the recent admission by Sartaj Aziz, advisor to the prime minister on foreign affairs, that the afghan Taliban’s leadership is in Pakistan.

And according to Sami Yousafzai, Newsweek’s correspondent for Pakistan, “If they’re using the hospitals, as pointed out by Sartaj Aziz, they’re also using the territory.” This fact, Yousafzai feels, has created unbelievable amounts of bad blood for Pakistan. “The Afghans now think that all the violence they’ve had to face over the last fifteen years, it’s all come from the other side of border.”

This creates an uneasy situation for President Ghani, who finds himself stuck between an enemy within his borders and an ally unwilling to play its part. What, then, can he do?

He could go to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), but it is highly unlikely that any of the full members will support him, says Yousafzai. And even if he was to get some form of backing, it would further antagonize an already shaky relationship with Pakistan. With options limited, Kabul has turned to Washington to play its part in getting Islamabad on track.

A scathing editorial by the New York Times titled ‘Time to put the Squeeze on Pakistan’, repeats what most of the western press has been saying for some time now: the key to peace in Afghanistan is Pakistan, and it’s not playing ball. There is also the no small matter of the Haqqani network as well, with both Washington and Kabul alleging that Siraj and co are now at the operational heart of the Taliban insurgency. It has long been alleged that the Haqqanis have close ties with the Pakistani establishment.

Afghanistan is now looking to have the Taliban declared ‘irreconcilable’ and pushing for military action against the group. Regardless of the outcome of the meeting of the Quadrilateral Coordination Committee (QCG), Pakistan will be hard pressed to take action against the Afghan Taliban within its borders, primarily for two reasons. The first is the extent to which Pakistan can influence the Afghan Taliban. As a former diplomat told me, “Even if we get them to the table, we can’t control the conversation.” And the second is the possibility of a violent backlash inside Pakistan. Over the past year, the country has made hard fought gains against terrorists holed up in the tribal regions. A long awaited limited operation has also gotten underway in the Punjab.

“To open up a new front, or even the possibility of a new front, at this time is inconceivable,” an intelligence officer admitted.

With Kabul and Islamabad at loggerheads about the way forward with the Taliban, it may fall to the other two members of the QCG, Beijing and Washington, to resolve the stalemate. Clearly, the United States will be looking for some semblance of peace in Afghanistan so that it may withdraw from the country with some respectability intact. However, given the recent slide in relations between the two countries, China seems to be best bet, with big projects planned not only in Pakistan, but Afghanistan as well. As Barnett Rubin, a leading expert on the region said at last year’s Lahore Literary Festival, “the economics of the region demand stability.”

It is under these vexing circumstances that the chiefs of the Pakistani and Chinese militaries have met very recently in Beijing, ostensibly to discuss the CPEC. “I’m certain the situation in Afghanistan will have also been discussed,” says journalist and author Ahmed Rashid. “The problem however is that for all intents and purposes, there has been no shift in policy on Pakistan’s side vis-a-vis the Afghan Taliban,” he argues.

With things remaining as they are, President Ashraf Ghani may find himself banging his head against a brick wall, unable to deliver peace to his people. What this will do to his presidency is anybody’s guess.