I am part of a WhatsApp group called Besties on which my closest female friends and I freely explore anything ranging from homemade brownies to American politics; marital concerns to childbirth; anxieties and fears to our mythical ‘reunion in Thailand’. This for me is frankly a lifeline. Just knowing that I can air my innermost thoughts and feelings with complete openness and expect compassion, support, excitement, or brutal honesty in return - depending on what is deemed necessary - is a great comfort.

But it’s International Men’s Day, so let’s talk about that. My husband, unlike me, has no equivalent lifeline in the form of a Besties WhatsApp group. To the best of my knowledge nor does my brother or indeed any other male friend or cousin of mine. They have plenty of friends and a reliable support network, no doubt, but that is not quite the same as what I have. I often wonder when and where the men in my life explore their feelings and discuss their moods; where they talk about love, rejection, inadequacy, failure or anxiety. Worryingly enough, I think it’s safe to say that most men just don’t. This generalisation, like all generalisations, will have several exceptions and if you happen to know or be a man that talks openly about his feelings and vulnerabilities then bravo! That is the new world order we need to aspire to. While we get there, unfortunately, we continue to inhabit a world where toxic masculinity prevails and is even encouraged.

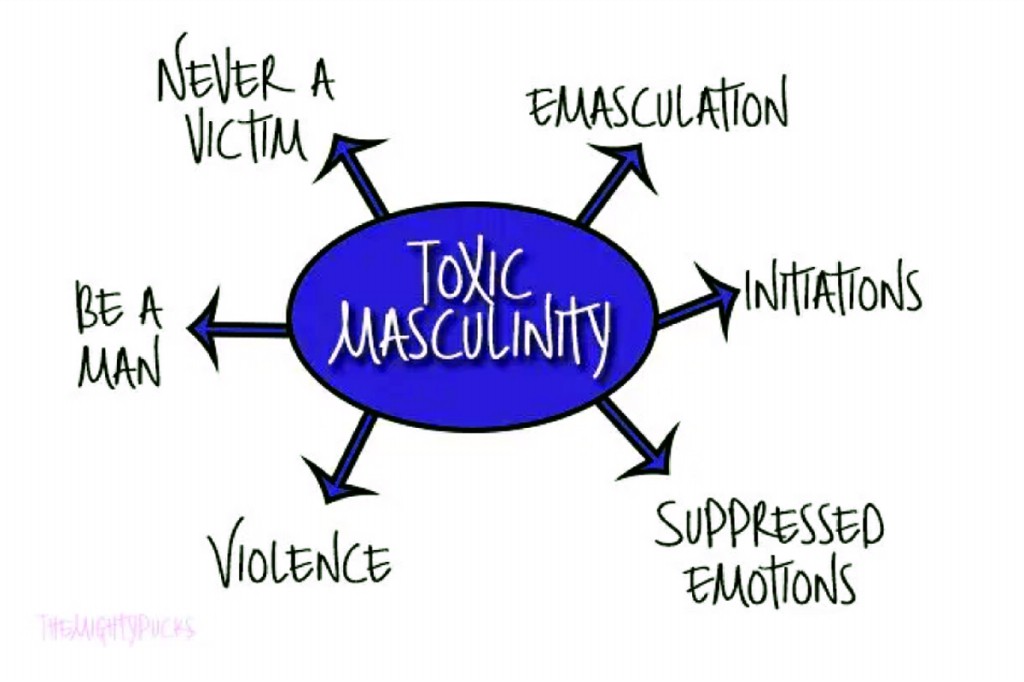

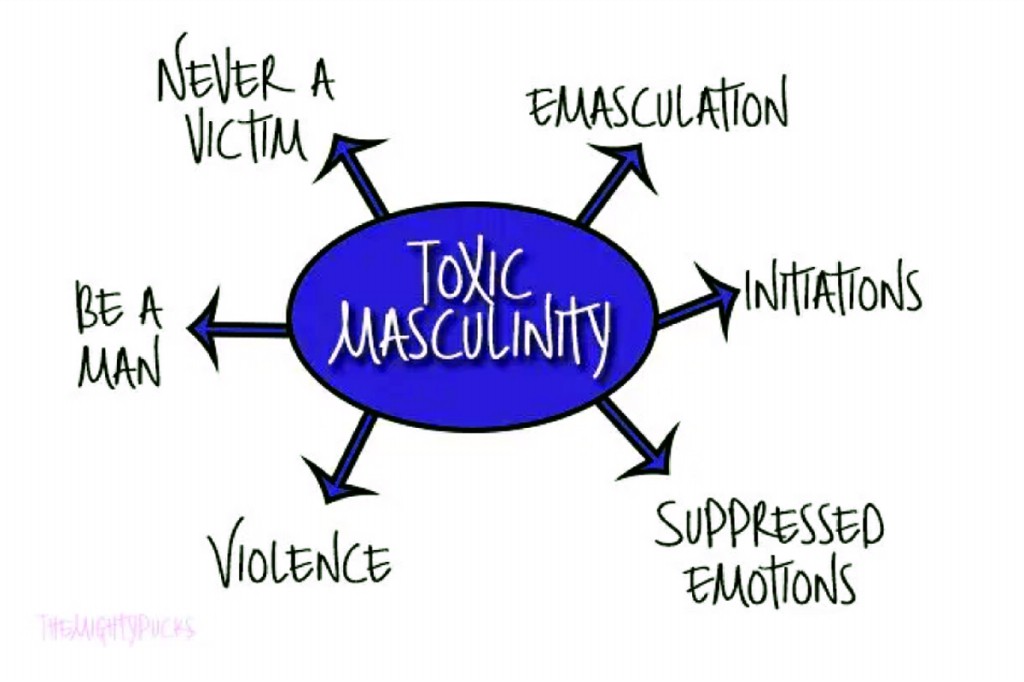

What exactly is toxic masculinity then? It’s a term that has gained real traction recently but its premise has existed, well, since the inception of human life! You don’t need to delve too deeply into Greek mythology to know that toxic masculinity has ancient roots, but rather more worryingly, is rampant today, centuries later. Toxic masculinity is a set of undesirable traits that are traditionally associated with male territory. These can include emotional and physical domination, aggressive behaviour, a tough exterior, the need to be infallible, the urge to be in control, unreasonable notions of success, the perception of immunity to danger and the avoidance being perceived as vulnerable - at all costs. In this realm, seeking help is seen as a sign of weakness, even when it comes to something as innocuous as seeking directions in a foreign city, leave alone seeking emotional support. Toxic masculinity also automatically limits the conversational scope available to men, allowing football, cricket, business, politics, films and travel to be staples but steering well clear of anything more emotional or ‘deep’. I do think it’s worth clarifying at this stage that not for a second am I suggesting men are incapable of deep or meaningful conversation, which would be both inaccurate and ludicrous. My observation is more with regards to social conditioning over hundreds of years which first saw masculinity as hunting deer and guarding the cave and now sees it as breadwinning and bantering over football. I have myself organised princess themed birthday parties for my daughter and racing car parties for my son, so I absolutely see myself as part of the problem. I have encouraged my son to go out and “kick a ball in the park” with his friends (always happens at a ‘safe distance’ - no danger of any real conversation) and invited my daughter’s friends to play indoors where they often paint, craft or bake over lovely conversations. I am part of the problem.

How stifling must it feel to have no meaningful outlets for one’s emotions? To have to cry in private, and even then, with some degree of shame. I cry freely and openly and almost always feel lighter as a result of it; it distresses me to think that society grudges men this most innate of human expressions. Can you imagine the loneliness that exists without open and meaningful communication? It seems foolish and unnatural to expect a human being to disconnect from their emotional sensitivity in the process of graduating into manhood. I have a 3-month-old baby boy who expresses himself though giggles, frowns, whispers and howls and human instinct dictates that we hold him, cradle him, rock and whisper sweet nothings to calm him down. I also have an 8-year-old son who falls into a tight embrace with us when he is hurting and wants me to cuddle him to sleep each night. To think that over the next few years these boys will somehow need to shed their emotional sensitivity and open need for love and support to become ‘masculine’ fills me with utter dread. The notion of ‘thought’ being masculine and ‘feeling’ feminine is pure conditioning and most definitely does not have to be our truth. The need to become emotionless to grow into a man is equally fallacious.

And to think that what I have just described is really the best-case scenario. Within toxic masculinity, depression, mental illness, anxiety, and suicide all fester and it’s not surprising that suicide rates are much higher for men as compared to women in the UK. Interestingly however, more women than men are diagnosed with depression - no doubt because they seek help more readily.

The best thing we can do to expedite a shift in paradigm is to start having these conversations early with our boys - at home, in school and more widely within society, literature and the media. It is vital that boys are given the space and support to create their own versions of what masculinity means to them instead of slotting into the framework available. Language is significant too, isn’t it? It’s not “gay” to talk about feelings nor should there ever be a need to “man up”. “Boys don’t cry” is about as mythical as unicorns - speaking of which, let your little boy buy one the next time you are in a toy shop!

I am lucky to be married to a man who defies all pre-existing stereotypes about masculinity. He adores opera, listens to classical music, makes bread, does the laundry, and hates football. But I can guarantee that he would readily agree that when it comes to the free and open expression of thoughts and feelings, he feels limited and restricted. Our children have often observed that “Daddy never cries”. It really is about time we stopped seeing that as a compliment.

Happy International Men’s Day!

The author received a PhD in English Literature from the University of Warwick and is an Associate Senior Leader at The Ridgeway Education Trust in Oxfordshire, England

But it’s International Men’s Day, so let’s talk about that. My husband, unlike me, has no equivalent lifeline in the form of a Besties WhatsApp group. To the best of my knowledge nor does my brother or indeed any other male friend or cousin of mine. They have plenty of friends and a reliable support network, no doubt, but that is not quite the same as what I have. I often wonder when and where the men in my life explore their feelings and discuss their moods; where they talk about love, rejection, inadequacy, failure or anxiety. Worryingly enough, I think it’s safe to say that most men just don’t. This generalisation, like all generalisations, will have several exceptions and if you happen to know or be a man that talks openly about his feelings and vulnerabilities then bravo! That is the new world order we need to aspire to. While we get there, unfortunately, we continue to inhabit a world where toxic masculinity prevails and is even encouraged.

What exactly is toxic masculinity then? It’s a term that has gained real traction recently but its premise has existed, well, since the inception of human life! You don’t need to delve too deeply into Greek mythology to know that toxic masculinity has ancient roots, but rather more worryingly, is rampant today, centuries later. Toxic masculinity is a set of undesirable traits that are traditionally associated with male territory. These can include emotional and physical domination, aggressive behaviour, a tough exterior, the need to be infallible, the urge to be in control, unreasonable notions of success, the perception of immunity to danger and the avoidance being perceived as vulnerable - at all costs. In this realm, seeking help is seen as a sign of weakness, even when it comes to something as innocuous as seeking directions in a foreign city, leave alone seeking emotional support. Toxic masculinity also automatically limits the conversational scope available to men, allowing football, cricket, business, politics, films and travel to be staples but steering well clear of anything more emotional or ‘deep’. I do think it’s worth clarifying at this stage that not for a second am I suggesting men are incapable of deep or meaningful conversation, which would be both inaccurate and ludicrous. My observation is more with regards to social conditioning over hundreds of years which first saw masculinity as hunting deer and guarding the cave and now sees it as breadwinning and bantering over football. I have myself organised princess themed birthday parties for my daughter and racing car parties for my son, so I absolutely see myself as part of the problem. I have encouraged my son to go out and “kick a ball in the park” with his friends (always happens at a ‘safe distance’ - no danger of any real conversation) and invited my daughter’s friends to play indoors where they often paint, craft or bake over lovely conversations. I am part of the problem.

Not for a second am I suggesting men are incapable of deep or meaningful conversation, which would be both inaccurate and ludicrous. My observation is more with regards to social conditioning over hundreds of years. which first saw masculinity as hunting deer and guarding the cave - and now sees it as breadwinning and bantering over football

How stifling must it feel to have no meaningful outlets for one’s emotions? To have to cry in private, and even then, with some degree of shame. I cry freely and openly and almost always feel lighter as a result of it; it distresses me to think that society grudges men this most innate of human expressions. Can you imagine the loneliness that exists without open and meaningful communication? It seems foolish and unnatural to expect a human being to disconnect from their emotional sensitivity in the process of graduating into manhood. I have a 3-month-old baby boy who expresses himself though giggles, frowns, whispers and howls and human instinct dictates that we hold him, cradle him, rock and whisper sweet nothings to calm him down. I also have an 8-year-old son who falls into a tight embrace with us when he is hurting and wants me to cuddle him to sleep each night. To think that over the next few years these boys will somehow need to shed their emotional sensitivity and open need for love and support to become ‘masculine’ fills me with utter dread. The notion of ‘thought’ being masculine and ‘feeling’ feminine is pure conditioning and most definitely does not have to be our truth. The need to become emotionless to grow into a man is equally fallacious.

And to think that what I have just described is really the best-case scenario. Within toxic masculinity, depression, mental illness, anxiety, and suicide all fester and it’s not surprising that suicide rates are much higher for men as compared to women in the UK. Interestingly however, more women than men are diagnosed with depression - no doubt because they seek help more readily.

The best thing we can do to expedite a shift in paradigm is to start having these conversations early with our boys - at home, in school and more widely within society, literature and the media. It is vital that boys are given the space and support to create their own versions of what masculinity means to them instead of slotting into the framework available. Language is significant too, isn’t it? It’s not “gay” to talk about feelings nor should there ever be a need to “man up”. “Boys don’t cry” is about as mythical as unicorns - speaking of which, let your little boy buy one the next time you are in a toy shop!

I am lucky to be married to a man who defies all pre-existing stereotypes about masculinity. He adores opera, listens to classical music, makes bread, does the laundry, and hates football. But I can guarantee that he would readily agree that when it comes to the free and open expression of thoughts and feelings, he feels limited and restricted. Our children have often observed that “Daddy never cries”. It really is about time we stopped seeing that as a compliment.

Happy International Men’s Day!

The author received a PhD in English Literature from the University of Warwick and is an Associate Senior Leader at The Ridgeway Education Trust in Oxfordshire, England