The recent gang rape of a woman on the Lahore motorway sparked outrage on social media with people demanding the immediate public hanging of the rapists. Prime Minister Imran Khan suggested “chemically castrating” the accused. Respected Islamic scholar Mawlana Tariq Jamil also broke his silence and cited co-education, western clothing, and late night travel as some of the reasons for the tragic incident. The Lahore Capital City Police Officer (CCPO), Umer Sheikh, who was directly in charge of the investigation, expressed his shock over the survivor’s decision to leave her house with her children during late hours of the night as well as the fact that she decided to take a dangerous route, when according to him, a “perfectly safe” alternate route was available. If anything, the above statements are a visual representation of why rape survivors choose to stay silent.

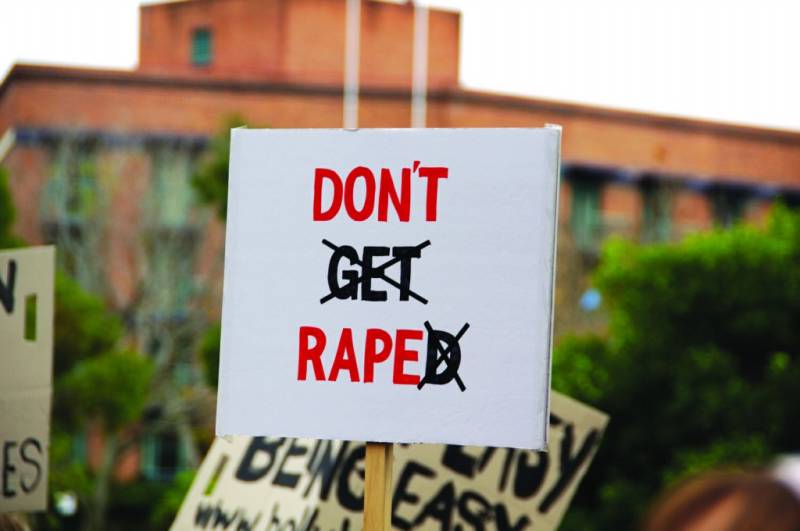

What is rape culture? A culture that normalizes rape, harassment, and other forms of sexual abuse caused by the collective attitude of individuals in a society. This normalization takes place as a result of patriarchal views about sex, gender, and sexuality. Rape culture not only produces rapists, but also rape apologists. Rape apologists can be identified by their reaction to the crime. How many times do we hear people ask all the wrong questions? What was she wearing? Who was she with? Why did she leave the house alone? Why was she out so late? Was she drunk? She must have led him on.

Pakistan’s most sought-after playwright, Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar, had some bizarre ideas on gender equality when asked about his views on the Aurat (Women’s) March that took place earlier this year. To quote, he said – “Do women have the ability to kidnap a man and gang-rape him? Can they show us that they are capable? No, right? Then how can they expect equality?” Here, Qamar clearly talks about “the ability to rape” as some sort of “machismo” that women can never achieve. What was more bizarre, however, was the amount of people that supported him. Women are coming to the streets to fight for their rights. They’re becoming assertive, opinionated, demanding equal pays, and becoming more vocal about the injustice they face every day. Men that are unwilling to give up their privilege cannot digest these threats to patriarchy. Rape culture allows them to maintain their position of power by belittling any chance of women empowerment.

Following the motorway gang-rape, social media was flooded with posts demanding public hangings. What remains missing, however, is a discourse on systematic change. While people are fixated on revenge, how do we make sure such crimes don’t take place in the future? The argument that “capital punishment instills fear in criminals” is futile. Some interesting posts that emerged following the motorway incident was a glorification of Ziaul Haq’s rule as many public hangings took place during his time. The social media posts read, “As a result of public hangings ordered by General Ziaul Haq, no rapes were reported during the next 10 years.” Such statements are tone-deaf at best. The passing of the Zina Ordinance as part of the Hudood Ordinances (1979) during Ziaul Haq’s military rule made it extremely difficult for women to prove allegations of rape, as it required them to present “four Muslim male witnesses.” Upon failing to present witnesses to the court, women were charged with adultery, jailed, or worse – sentenced to death by stoning. In 2002, Zafran Bibi, a blind unmarried woman from the North-West Frontier, became an example of one of the many women who bore the brunt of Zia’s patriarchal laws years later. A month after she reported the rape, the judge ruled it as adultery (citing her pregnancy as “proof” of pre-marital sex.) She was sentenced to death by stoning. It is no surprise that rape rates remained low during Zia-Ul-Haq’s time as well as years later when the initial Zina Ordinance was still in effect until 2006.

According to a report published in 2003 by the National Commission on the status of Women (NCSW), 80 percent of women were incarcerated because “they had failed to prove rape charges and were consequently convicted of adultery.” While amendments in laws have taken place since then, sexual harassment laws remain weak in Pakistan. The first systematic change needs to come from the justice system itself where the victim is provided a fair, humiliation free trial without any questions being raised on the victim’s integrity.

Speaking of capital punishments and chemical castrations, Prime Minister Imran Khan came out looking as a Messiah for his followers when he suggested the harshest punishment that came to mind. In reality, his comments have added no value towards effective change. There are two reasons why his statement is redundant; first, after expressing his support for capital punishments, Khan quickly pointed out that nothing is in his control because of the GSP plus status given to developing countries including Pakistan. If this were to be normalized, it would hurt international relations as capital punishments are not favored by the EU; second, ruling out the possibility of a public hanging, Prime Minister Khan avoided a discussion on other possible solutions. As the prime minister of a country where sexual violence is widespread, Khan could’ve diverted the discussion towards a more productive discourse on the measures his government has taken to ensure the safety of women in Pakistan; a conversation on sex education and consent awareness, perhaps? No such statement has been made, yet.

There is ample empirical evidence to suggest that instilling sex education in schools from an early age helped children better understand the importance of consent as well as the importance of speaking up in cases of violation/crossing boundaries. A report titled “The Effect of Sexual Education on Sexual Assault Prevention” shows “…that comprehensive sexual education by groups such as Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Center of North Carolina (APPCNC), Orange County Rape Crisis Center (OCRCC), and Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs (WCSAP) have demonstrated their success in creating a culture that values, expects, and demands sexual consent.” The second systematic change should come from educational institutes in Pakistan. Schools and colleges could maybe start by considering not skipping the chapter on reproduction. This leaves students to rely on porn sites (where rape and exploitation of minors is greatly normalized) as their only source of information surrounding “taboo” topics including sex, menstruation, and reproduction – giving rise to unrealistic, unhealthy, and dangerous expectations.

There is also enough evidence to suggest that capital punishments have little or no effect on the rate of crimes against women. According to a former supreme court judge Ashok Kumar, “Nowhere ever has capital punishment been helpful in preventing rape. If it had, why would there still be so much crime? There was a reason the world moved away from capital punishment. It undermined right to life and has proven problematic everywhere that it was practiced in the world.” Capital punishments also reduce the chances of the victim getting justice. Due to the severity of the punishment if convicted, lack of evidence and doubt regarding the integrity of the victim (especially in countries like Pakistan where victim blaming is rampant), chances of persecution are greatly diminished. To add further, “Robust laws would in fact have a very limited impact in reducing the crime unless they are accompanied with a change in the attitudes of the police, judiciary, government officers and society.”

When the views of the Islamic Scholar Tariq Jamil, CCPO Umer Sheikh, and playwright Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar, all individuals with immense power and influence, are representative of the entire country, what good do we expect from capital punishment? In a society where women are already viewed as nothing beyond objects of sexual desire, Tariq Jamil has gone ahead and suggested the banning of co-education. Wanting to create a society where the co-existence of men and women is seen as unnatural would further sexualize women because of the ideology that women need to be kept “hidden” from men. What is this segregation about? The co-existence of men and women is a normal reality in all spheres of life; be it school, university, work, family, social circles, etc. and we need to be taught how to co-exist with respect and dignity.

Chanting “hang the rapist” as part of one’s rage makes sense, but does it help eliminate rape culture? When “Hang the rapist!” is followed by “…but why was she out so late though?”, what is the point? When one says “hang the rapist”, does it help in changing the victim-blamey mindset that seems to be widespread across Pakistan? Truth is – it completely pushes the narrative towards a reaction to the crime rather than acknowledging the root cause – misogynist attitudes. What is needed is the administering of effective measures to reduce the risk of the crime happening in the first place. What is needed is providing the survivor with sufficient relief through accessible rehabilitation programs. What is needed is treating the survivor with respect and dissociating what happened to her with her honor. A transformation in the education and justice system, normalization of sex education, conversations on the importance of consent, and the breaking of taboos surrounding menstruation and reproduction is what Pakistan desperately needs.

The writer works for the Human Rights Department of Sindh as a data analyst as part of the Young Expert Program (YEP) funded by the European Union

What is rape culture? A culture that normalizes rape, harassment, and other forms of sexual abuse caused by the collective attitude of individuals in a society. This normalization takes place as a result of patriarchal views about sex, gender, and sexuality. Rape culture not only produces rapists, but also rape apologists. Rape apologists can be identified by their reaction to the crime. How many times do we hear people ask all the wrong questions? What was she wearing? Who was she with? Why did she leave the house alone? Why was she out so late? Was she drunk? She must have led him on.

Pakistan’s most sought-after playwright, Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar, had some bizarre ideas on gender equality when asked about his views on the Aurat (Women’s) March that took place earlier this year. To quote, he said – “Do women have the ability to kidnap a man and gang-rape him? Can they show us that they are capable? No, right? Then how can they expect equality?” Here, Qamar clearly talks about “the ability to rape” as some sort of “machismo” that women can never achieve. What was more bizarre, however, was the amount of people that supported him. Women are coming to the streets to fight for their rights. They’re becoming assertive, opinionated, demanding equal pays, and becoming more vocal about the injustice they face every day. Men that are unwilling to give up their privilege cannot digest these threats to patriarchy. Rape culture allows them to maintain their position of power by belittling any chance of women empowerment.

Following the motorway gang-rape, social media was flooded with posts demanding public hangings. What remains missing, however, is a discourse on systematic change. While people are fixated on revenge, how do we make sure such crimes don’t take place in the future? The argument that “capital punishment instills fear in criminals” is futile. Some interesting posts that emerged following the motorway incident was a glorification of Ziaul Haq’s rule as many public hangings took place during his time. The social media posts read, “As a result of public hangings ordered by General Ziaul Haq, no rapes were reported during the next 10 years.” Such statements are tone-deaf at best. The passing of the Zina Ordinance as part of the Hudood Ordinances (1979) during Ziaul Haq’s military rule made it extremely difficult for women to prove allegations of rape, as it required them to present “four Muslim male witnesses.” Upon failing to present witnesses to the court, women were charged with adultery, jailed, or worse – sentenced to death by stoning. In 2002, Zafran Bibi, a blind unmarried woman from the North-West Frontier, became an example of one of the many women who bore the brunt of Zia’s patriarchal laws years later. A month after she reported the rape, the judge ruled it as adultery (citing her pregnancy as “proof” of pre-marital sex.) She was sentenced to death by stoning. It is no surprise that rape rates remained low during Zia-Ul-Haq’s time as well as years later when the initial Zina Ordinance was still in effect until 2006.

According to a report published in 2003 by the National Commission on the status of Women (NCSW), 80 percent of women were incarcerated because “they had failed to prove rape charges and were consequently convicted of adultery.” While amendments in laws have taken place since then, sexual harassment laws remain weak in Pakistan. The first systematic change needs to come from the justice system itself where the victim is provided a fair, humiliation free trial without any questions being raised on the victim’s integrity.

Speaking of capital punishments and chemical castrations, Prime Minister Imran Khan came out looking as a Messiah for his followers when he suggested the harshest punishment that came to mind. In reality, his comments have added no value towards effective change. There are two reasons why his statement is redundant; first, after expressing his support for capital punishments, Khan quickly pointed out that nothing is in his control because of the GSP plus status given to developing countries including Pakistan. If this were to be normalized, it would hurt international relations as capital punishments are not favored by the EU; second, ruling out the possibility of a public hanging, Prime Minister Khan avoided a discussion on other possible solutions. As the prime minister of a country where sexual violence is widespread, Khan could’ve diverted the discussion towards a more productive discourse on the measures his government has taken to ensure the safety of women in Pakistan; a conversation on sex education and consent awareness, perhaps? No such statement has been made, yet.

Chanting “hang the rapist” as part of one’s rage makes sense, but does it help eliminate rape culture?

There is ample empirical evidence to suggest that instilling sex education in schools from an early age helped children better understand the importance of consent as well as the importance of speaking up in cases of violation/crossing boundaries. A report titled “The Effect of Sexual Education on Sexual Assault Prevention” shows “…that comprehensive sexual education by groups such as Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Center of North Carolina (APPCNC), Orange County Rape Crisis Center (OCRCC), and Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs (WCSAP) have demonstrated their success in creating a culture that values, expects, and demands sexual consent.” The second systematic change should come from educational institutes in Pakistan. Schools and colleges could maybe start by considering not skipping the chapter on reproduction. This leaves students to rely on porn sites (where rape and exploitation of minors is greatly normalized) as their only source of information surrounding “taboo” topics including sex, menstruation, and reproduction – giving rise to unrealistic, unhealthy, and dangerous expectations.

There is also enough evidence to suggest that capital punishments have little or no effect on the rate of crimes against women. According to a former supreme court judge Ashok Kumar, “Nowhere ever has capital punishment been helpful in preventing rape. If it had, why would there still be so much crime? There was a reason the world moved away from capital punishment. It undermined right to life and has proven problematic everywhere that it was practiced in the world.” Capital punishments also reduce the chances of the victim getting justice. Due to the severity of the punishment if convicted, lack of evidence and doubt regarding the integrity of the victim (especially in countries like Pakistan where victim blaming is rampant), chances of persecution are greatly diminished. To add further, “Robust laws would in fact have a very limited impact in reducing the crime unless they are accompanied with a change in the attitudes of the police, judiciary, government officers and society.”

When the views of the Islamic Scholar Tariq Jamil, CCPO Umer Sheikh, and playwright Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar, all individuals with immense power and influence, are representative of the entire country, what good do we expect from capital punishment? In a society where women are already viewed as nothing beyond objects of sexual desire, Tariq Jamil has gone ahead and suggested the banning of co-education. Wanting to create a society where the co-existence of men and women is seen as unnatural would further sexualize women because of the ideology that women need to be kept “hidden” from men. What is this segregation about? The co-existence of men and women is a normal reality in all spheres of life; be it school, university, work, family, social circles, etc. and we need to be taught how to co-exist with respect and dignity.

Chanting “hang the rapist” as part of one’s rage makes sense, but does it help eliminate rape culture? When “Hang the rapist!” is followed by “…but why was she out so late though?”, what is the point? When one says “hang the rapist”, does it help in changing the victim-blamey mindset that seems to be widespread across Pakistan? Truth is – it completely pushes the narrative towards a reaction to the crime rather than acknowledging the root cause – misogynist attitudes. What is needed is the administering of effective measures to reduce the risk of the crime happening in the first place. What is needed is providing the survivor with sufficient relief through accessible rehabilitation programs. What is needed is treating the survivor with respect and dissociating what happened to her with her honor. A transformation in the education and justice system, normalization of sex education, conversations on the importance of consent, and the breaking of taboos surrounding menstruation and reproduction is what Pakistan desperately needs.

The writer works for the Human Rights Department of Sindh as a data analyst as part of the Young Expert Program (YEP) funded by the European Union