Leh, the capital of Ladakh and the first major town as one descends from the Tibetan plateau and the Karakoram mountain range, has been variously described as a “true little capital, the seat of a tiny cosmopolitan world” and it has been said that “what Port Said is to the Suez Canal, Leh is to the Central Asian trade road” (R. L. Kennion, British Joint Commissioner, Ladakh, 1910 ).

The Central Asian towns south of the Silk Road were also great centres of Buddhism. So, Buddhist missionaries passed through Ladakh on their way to Central Asia and Tibet on their mission to propagate the faith. Historically Leh from time immemorial has also been an important trade centre for Central Asia. Hadud-e-Alam, a 9th century Persian manuscript, mentions Ladakh’s trade links with neighbouring countries. From the 9th century onwards, the geographic proximity of Ladakh to the Central Asian towns, whose people embraced Islam around that time, can be gauged from the fact that they traveled to Makkah for Hajj via Leh. Thus this important town became a major trading centre dominated by Central Asian traders. Their lingua franca, a Turkic language, gained popularity in Leh and Nubra, the village en route the Leh-Yarkand road. Many Turkic words found their way into the Ladakhi language and are still part of it. Some Central Asian traders, all Muslims, settled in Leh and married Ladakhi women. These families, later called Argons, have grown and branched out and are fully integrated into Ladakhi society.

The trade spread to other geographies and nationalities. Punjabi traders used Kulu and Lahaul route for movement of goods. However this route was substantially superseded by the Rawalpindi-Srinagar route, especially when a motorable road was built between Rawalpindi and Srinagar in the last decade of the 19th century. The Kashmiri traders who, by a treaty, had a monopoly over the pashmina trade, made good use of this privilege and also of the newly created road access.

Srinagar became a major market for Central Asian goods where sarais were built for Central Asian traders. Kashmiri traders expanded on the already existing links with Leh and most of them became part of the Argon community. Alexander Cunningham in his book Ladakh (1854) reported that there were 60 merchants from Kashmir as against 20 merchants from Bashahr and Punjab. The non-Kashmiri merchants would only operate out of Leh while the Kashmiris were going across the Karakorum to Central Asia and into Tibet. These figures only substantiate the fact that Kashmiris were dominating the Central Asian trade via Leh. 19th-century European adventurers, explorers and political missions to Ladakh and Central Asia found that Kashmiris were holding important positions in governance and trade. Sven Hedin, the geographer and great explorer and author of Trans Himalayas (1909) mentions that Khwaja Nasar Shah was a prominent Muslim in Leh and was famous in the whole of inner Asia. He also reported that the members of this family have been leading for 50 years ‘Lopchaq’, a revered Ladakhi religious festival that takes place every two years and also sending a trade delegation to Tibet. This delegation would call on the Dalai Lama and present gifts and tribute on behalf of the Leh Government and various monasteries. Sven Hedin also mentions that this family has residences and business establishments in Lhasa, Ghartoq, Yarkand and Srinagar. Another prominent Kashmiri Muslim, Khawaja Ghulam Rasool, was given the title of Khan Bahadur by the British and a gold medal by the Swedish monarchy. He chould be the only Kashmiri in the history of British India to have been invested with this title. Haji Gulam Mohamad and Haji Faizullah, two more Kashmiris, were advisors to the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

The Silk Route traders travelled via Ladakh through the Eastern Karakorum passes carrying cargo comprising silk, carpets, silver, coral, velvet, brocades, charas and other drugs. These were then transported to Kashmir and Punjab. In the other direction spices, shawls, honey, dyes, shoes and precious stones moved towards Tibet and Central Asian cities.

Alongside the exchange of goods, a composite culture evolved within the communities and Central Asian trader community comprising Yarkandis and Kashmiris. They produced adventurers, administrators, high-ranking palace officials and, of course, traders of substance. However, post-Independence and then with the closure of the international routes, this community was confined to Leh and with the passage of time suffered a change in fortunes. This also resulted in a progressive loss of their status and cultural spaces. A feeling of disempowerment and alienation crept in the community.

It was in this background that the idea of setting up a memorial for the Central Asian cultural landscape was born. Anjuman Moinul Islam, the local Muslim trust, was concerned with the dilution of their community’s role and prominence in Ladakh. This trust owns land and other properties in Leh including the most prominent Jamia Masjid in the town. Adjacent to this mosque there was another old mosque, predating the Jamia Masjid, by the name of Tsa Soma Mosque, a mud structure that had crumbled and fallen in disuse. The Anjuman approached the Tourism Department, while this writer was posted there, for assistance to create an economic asset and for landscaping the area around Tsa Soma Mosque.

It did not take much in the way of persuasion to bring them on board to convert the Tsa Soma Mosque area into a museum that would document and project the past achievements of this community in sustaining trade and cultural connections. Ladakh has been attracting professionals and experts in Tibetan and Central Asian architecture, livelihoods and traditional lifestyles. These included the Tibet Heritage Fund, at the time led by Andre Alexander, one of the leading NGOs engaged in preservation of the old town of Leh. They readily agreed to restore Tsa Soma Mosque and also construct a museum and research facility on the premises of the mosque. The State Tourism Department and the Anjuman came together and pooled in the resources for setting up the museum. A committee of experts and Anjuman representatives was constituted and the museum was registered under the J&K Societies Registration Act in 2007 under the name of the ‘Trans Himalayan Trade and Cultural Society’. The museum was conceived as a cultural space depicting the linkages between religions and cultures of Tibet, Central Asia and Kashmir.

The restoration of the mosque took three years. Subsequently construction of the museum building was taken up and completed by 2014. This three-storey building with galleries and projections, housing the museum, is a masterpiece and a unique representation of traditional Tibetan architecture built with local stones, wood and locally available mud for binding. The structure, like similar structures on the Tibetan plateau, is earthquake-resistant, with facilities for display and storage of artifacts. The building has a library for which books were donated by locals as well as other well-wishers. The library was also meant to be an archive – an academic and intellectual space where seminars and workshops could be held.

The Argon families have donated antiques, artifacts and manuscripts to the museum. The ground floor of the museum has a photo display of the geology and antiquity of Ladakh. Thus rock art and rock inscriptions, ranging from prehistoric times to those of the travelers, including some Arabic inscriptions, figure in this section. The largest and most significant collection has come from the Jamia Masjid. Precious Yarkandi carpets, highly valued manuscripts and other items that were stored or used in the Jamia Masjid were transferred to the museum. These include a sacred staff donated by the Head Lama of Hemis Gumpha.

Abdul Ghani Sheikh, an eminent historian of Ladakh and the most important member of the museum committee during its formative years, in his essay on Islamic architecture in Leh, has written that when Jamia Masjid was first built in 17th century, the Head Lama of Hemis monastery, Stagtsang Raspa, presented the wooden staff to the imam. It was kept at the mosque as a relic. The carpets were made especially for the mosque by wealthy Central Asian traders.

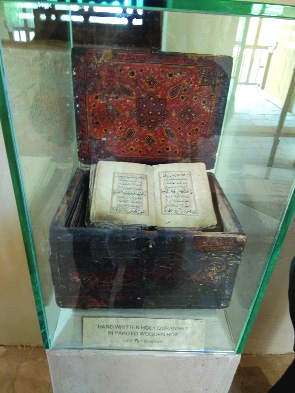

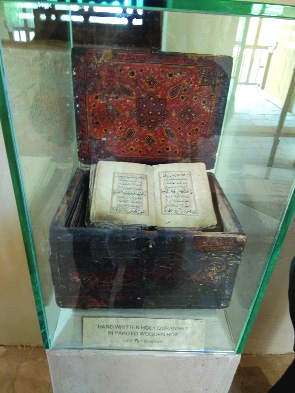

In the manuscript section, shajras of saints and sufis, most of them descendants of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and some from the Rightly Guided Caliphs, are a major attraction. A shajra can be about thirty feet long, calligraphed on handmade paper. Other artifacts of interest are boxes that were used in carrying precious cargo over the mountainous terrain for more than 500 miles on camel or horseback. The two leather pitchers used for carrying water on this journey look like earthenware – until one feels them.

This writer travelled to Nubra and other distant villages along the Silk Route in 2010 with Abdul Ghani Sheikh, Captain Ghulam Qadir and Mohamad Ayub, members of the museum committee, seeking objects and donations from the community members living in those distant lands. The Imam of Dixsit mosque, Nubra, donated the only carpet that he had inherited from his ancestors as his prayer rug. He was left with a grass mat for his prayers.

The present management of the museum and the elected body of Anjuman Moinul Islam have shown great interest and dedication to the institution. They see the museum as an instrument of dignity, an expression of their aspirations and a means of empowerment.

The author is former Director General Tourism, Jammu and Kashmir. He may be reached at saleembeg@gmail.com)

The Central Asian towns south of the Silk Road were also great centres of Buddhism. So, Buddhist missionaries passed through Ladakh on their way to Central Asia and Tibet on their mission to propagate the faith. Historically Leh from time immemorial has also been an important trade centre for Central Asia. Hadud-e-Alam, a 9th century Persian manuscript, mentions Ladakh’s trade links with neighbouring countries. From the 9th century onwards, the geographic proximity of Ladakh to the Central Asian towns, whose people embraced Islam around that time, can be gauged from the fact that they traveled to Makkah for Hajj via Leh. Thus this important town became a major trading centre dominated by Central Asian traders. Their lingua franca, a Turkic language, gained popularity in Leh and Nubra, the village en route the Leh-Yarkand road. Many Turkic words found their way into the Ladakhi language and are still part of it. Some Central Asian traders, all Muslims, settled in Leh and married Ladakhi women. These families, later called Argons, have grown and branched out and are fully integrated into Ladakhi society.

The trade spread to other geographies and nationalities. Punjabi traders used Kulu and Lahaul route for movement of goods. However this route was substantially superseded by the Rawalpindi-Srinagar route, especially when a motorable road was built between Rawalpindi and Srinagar in the last decade of the 19th century. The Kashmiri traders who, by a treaty, had a monopoly over the pashmina trade, made good use of this privilege and also of the newly created road access.

Srinagar became a major market for Central Asian goods where sarais were built for Central Asian traders. Kashmiri traders expanded on the already existing links with Leh and most of them became part of the Argon community. Alexander Cunningham in his book Ladakh (1854) reported that there were 60 merchants from Kashmir as against 20 merchants from Bashahr and Punjab. The non-Kashmiri merchants would only operate out of Leh while the Kashmiris were going across the Karakorum to Central Asia and into Tibet. These figures only substantiate the fact that Kashmiris were dominating the Central Asian trade via Leh. 19th-century European adventurers, explorers and political missions to Ladakh and Central Asia found that Kashmiris were holding important positions in governance and trade. Sven Hedin, the geographer and great explorer and author of Trans Himalayas (1909) mentions that Khwaja Nasar Shah was a prominent Muslim in Leh and was famous in the whole of inner Asia. He also reported that the members of this family have been leading for 50 years ‘Lopchaq’, a revered Ladakhi religious festival that takes place every two years and also sending a trade delegation to Tibet. This delegation would call on the Dalai Lama and present gifts and tribute on behalf of the Leh Government and various monasteries. Sven Hedin also mentions that this family has residences and business establishments in Lhasa, Ghartoq, Yarkand and Srinagar. Another prominent Kashmiri Muslim, Khawaja Ghulam Rasool, was given the title of Khan Bahadur by the British and a gold medal by the Swedish monarchy. He chould be the only Kashmiri in the history of British India to have been invested with this title. Haji Gulam Mohamad and Haji Faizullah, two more Kashmiris, were advisors to the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

The Silk Route traders travelled via Ladakh through the Eastern Karakorum passes carrying cargo comprising silk, carpets, silver, coral, velvet, brocades, charas and other drugs. These were then transported to Kashmir and Punjab. In the other direction spices, shawls, honey, dyes, shoes and precious stones moved towards Tibet and Central Asian cities.

Alongside the exchange of goods, a composite culture evolved within the communities and Central Asian trader community comprising Yarkandis and Kashmiris. They produced adventurers, administrators, high-ranking palace officials and, of course, traders of substance. However, post-Independence and then with the closure of the international routes, this community was confined to Leh and with the passage of time suffered a change in fortunes. This also resulted in a progressive loss of their status and cultural spaces. A feeling of disempowerment and alienation crept in the community.

It was in this background that the idea of setting up a memorial for the Central Asian cultural landscape was born. Anjuman Moinul Islam, the local Muslim trust, was concerned with the dilution of their community’s role and prominence in Ladakh. This trust owns land and other properties in Leh including the most prominent Jamia Masjid in the town. Adjacent to this mosque there was another old mosque, predating the Jamia Masjid, by the name of Tsa Soma Mosque, a mud structure that had crumbled and fallen in disuse. The Anjuman approached the Tourism Department, while this writer was posted there, for assistance to create an economic asset and for landscaping the area around Tsa Soma Mosque.

It did not take much in the way of persuasion to bring them on board to convert the Tsa Soma Mosque area into a museum that would document and project the past achievements of this community in sustaining trade and cultural connections. Ladakh has been attracting professionals and experts in Tibetan and Central Asian architecture, livelihoods and traditional lifestyles. These included the Tibet Heritage Fund, at the time led by Andre Alexander, one of the leading NGOs engaged in preservation of the old town of Leh. They readily agreed to restore Tsa Soma Mosque and also construct a museum and research facility on the premises of the mosque. The State Tourism Department and the Anjuman came together and pooled in the resources for setting up the museum. A committee of experts and Anjuman representatives was constituted and the museum was registered under the J&K Societies Registration Act in 2007 under the name of the ‘Trans Himalayan Trade and Cultural Society’. The museum was conceived as a cultural space depicting the linkages between religions and cultures of Tibet, Central Asia and Kashmir.

The restoration of the mosque took three years. Subsequently construction of the museum building was taken up and completed by 2014. This three-storey building with galleries and projections, housing the museum, is a masterpiece and a unique representation of traditional Tibetan architecture built with local stones, wood and locally available mud for binding. The structure, like similar structures on the Tibetan plateau, is earthquake-resistant, with facilities for display and storage of artifacts. The building has a library for which books were donated by locals as well as other well-wishers. The library was also meant to be an archive – an academic and intellectual space where seminars and workshops could be held.

The Argon families have donated antiques, artifacts and manuscripts to the museum. The ground floor of the museum has a photo display of the geology and antiquity of Ladakh. Thus rock art and rock inscriptions, ranging from prehistoric times to those of the travelers, including some Arabic inscriptions, figure in this section. The largest and most significant collection has come from the Jamia Masjid. Precious Yarkandi carpets, highly valued manuscripts and other items that were stored or used in the Jamia Masjid were transferred to the museum. These include a sacred staff donated by the Head Lama of Hemis Gumpha.

Abdul Ghani Sheikh, an eminent historian of Ladakh and the most important member of the museum committee during its formative years, in his essay on Islamic architecture in Leh, has written that when Jamia Masjid was first built in 17th century, the Head Lama of Hemis monastery, Stagtsang Raspa, presented the wooden staff to the imam. It was kept at the mosque as a relic. The carpets were made especially for the mosque by wealthy Central Asian traders.

In the manuscript section, shajras of saints and sufis, most of them descendants of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) and some from the Rightly Guided Caliphs, are a major attraction. A shajra can be about thirty feet long, calligraphed on handmade paper. Other artifacts of interest are boxes that were used in carrying precious cargo over the mountainous terrain for more than 500 miles on camel or horseback. The two leather pitchers used for carrying water on this journey look like earthenware – until one feels them.

This writer travelled to Nubra and other distant villages along the Silk Route in 2010 with Abdul Ghani Sheikh, Captain Ghulam Qadir and Mohamad Ayub, members of the museum committee, seeking objects and donations from the community members living in those distant lands. The Imam of Dixsit mosque, Nubra, donated the only carpet that he had inherited from his ancestors as his prayer rug. He was left with a grass mat for his prayers.

The present management of the museum and the elected body of Anjuman Moinul Islam have shown great interest and dedication to the institution. They see the museum as an instrument of dignity, an expression of their aspirations and a means of empowerment.

The author is former Director General Tourism, Jammu and Kashmir. He may be reached at saleembeg@gmail.com)