If someone asked me to describe Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro’s book in one or two lines, I would say, “It is a book of words and marks about ancient Karachi.” The words shared by the people, and documented by the author tell stories about Karachi’s rock art. The ‘marks’ over the rocks signify cultural identity, spiritual beliefs, cultural expression and rituals of the inhabitants. I have reviewed this book with one purpose: to entice readers to explore this remarkable work from cover to cover. But, before that I congratulate the Dr NA Baloch Institute of Heritage Research for publishing such an outstanding academic book.

The book consists of eight chapters.

The first chapter “Discovery of Rock Paintings in Karachi” reveals how the author discovered some sites located at Gadap taluka, Karachi. This chapter tells that important sites are Lahut (Nai Mol) and Rahim Bakhsh village, where rock carvings on bedrock feature various motifs such as geometric designs, shoeprints and arrows. However, locals believe that shoeprints belong to revered saints. This reflects a deep connection between the landscape and spiritual beliefs, particularly regarding a saint from the Arabian peninsula. In the Maher Valley, similar patterns of symbol veneration are observed, especially with footprint engravings attributed to Hazrat Ali (AS).

The Maher Valley is home to numerous petroglyphs, especially at Baithi Lak and near the Lahut rock shelter, adorned with sandstone engravings that enrich the cultural landscape. This chapter discusses petroglyphs and pictograms, particularly of Gadap Taluka. However, veneration art/symbols in the Maher valley illustrates the enduring legacy of cultural practices that continue to shape the lives of local inhabitants. In addition to that, the Maher valley also has cup-marks, various imprints and Buddhist engravings.

Title: Ancient Karachi: Reflections on Rock Art and Megaliths

Author: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Photographs: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Price: Rs 2,000/-

Year: 2024

Publishers: Dr NA Baloch Institute of Heritage Research, Jamshoro, Culture, Tourism, Antiquities and Archives Department, Government of Sindh

In Chapter 2, titled “The Cup-Marks in Gadap,” the author explores various prehistoric and Bronze Age sites that have previously received little scholarly attention. The valleys of Maher, Kand Jhang, Moidan, Kathore, and Thohar Kanaro are rich in archaeological significance, particularly known for their megaliths and rock art. The chapter specifically investigates the cup-marks in Gadap Valley, detailing their locations and interpretations while highlighting the ongoing mystery surrounding their purpose. The cup-marks are identified at seven important sites, including Babro Hill, Thohar Kanaro and Kararo Muqam. Local theories about these cupules vary, with some suggesting they served as ‘milking pots.’ At Babro Hill, located about 40 km north of Gadap, the author identifies six groups of cupules on a limestone surface, demonstrating consistent orientation and varying depths that suggest symbolic rather than utilitarian uses, possibly as markers or calendars for ancient inhabitants.

The author discusses the cup-marks at Kararo Muqam, suggesting they may represent ancient star maps or landscape features – including the menhir at Thohar Kanaro. It is adorned with petroglyphs and serves as a waypoint along ancient trade routes. At Lahut Tar, cupules arranged like a game board indicate possible communication among shepherds. The author emphasises the cultural significance of these artifacts, linking them to contemporary practices and community memory. Sites like Melo Buthi and Gidran Waro Gharoto add to the narrative, with cupules near ancient graveyards and rock carvings, suggesting ritualistic uses, possibly for collecting rainwater or communal activities. This chapter conform that Gadap Taluka illustrate a complex interplay of communication, ritual, and cultural memory among both ancient and contemporary communities.

I found that all chapters are organised in a way to narrate story uninterrupted, thus Chapter 3, titled “From Human Footprints to Animal Tracks: Imprints on the Rocks of Karachi,” examines the prehistoric rock art of Karachi’s Malir district. It focuses on engravings of animal tracks, human footprints, handprints, and shoeprints. These motifs are primarily found at sites like Lahut Tar, Gidran-Waro-Gharoto, and Thado Dam, documenting tracks of various species, including jackals, wolves, and leopards. Dr Kalhoro provides a geographical overview, detailing the exact locations of Lahut Tar and Lahut Buthi. These sites showcase a variety of handprints and shoeprints, often accompanied by the names of their creators. The author emphasises the cultural significance of these engravings as historical records left by ancient hunters and shepherds. They offer insights into the types of animals that once roamed the area and the lives of its inhabitants. The chapter highlights the diversity of motifs, including animal tracks and unique bird engravings not reported elsewhere in Pakistan. This uniqueness underscores the cultural and historical importance of Sindh’s rock art. The chapter also compares these findings to global rock art traditions, where handprints and footprints serve as memorial signs or cultural markers.

The author calls attention to the cultural reverence that these megaliths still hold for local communities, urging for more research and preservation efforts

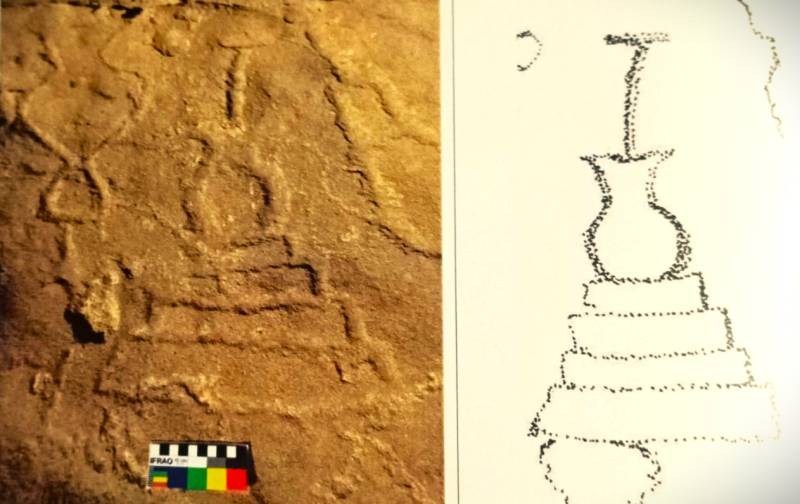

The author, with the aim of broadening readers’ perspectives, examines “Stupa Images in Petroglyphs of Karachi” as Chapter 4. In this chapter Dr Kalhoro examines the depictions of stupas in the rock art of Karachi and the Sindh-Kohistan belt. He begins by highlighting the importance of Buddhist rock art in Pakistan. He references foundational scholars like Ahmad Hasan Dani, Karl Jettmar from a Joint German-Pakistani research mission, and Luca Maria Olivieri the Italian archaeologist – all of whom documented and identified Buddhist rock carvings. This historical context sets the stage for understanding these artistic expressions found in Karachi and its hilly range.

Notably, prior to Dr Kalhoro’s research, the rock art in Sindh was largely overlooked. However, early observations, such as those by Majumdar in 1934, failed to capture the full diversity of these sites. The author classifies three main types of stupa images found in Karachi and Jamshoro. The first type are the multi-storey stupas with domes. The second type includes tower-like stupas, which can be with or without domes. The third type features oval, triangular and tower-like stupas with trident-shaped finials. This categorisation helps organise the variety of stupa imagery in the region. The chapter also emphasises major sites, particularly Lahut Tar, which has multiple stupa images. Here, the largest stupa is depicted on a boulder. It features intricate details, including a rectangular platform and a circular dome. Some important sites in the area are Thado Dam and Gidran-Waro-Gharoto, and these also feature stupas, but many are weathered or vandalised.

According to Dr Kalhoro, these stupa images offer insights into the ancient Buddhist communities that once thrived in ancient Karachi and its surroundings. However, he points out that the architectural styles reflected in these images indicate a noteworthy Buddhist presence throughout pre-Islamic Sindh. At the end of this chapter, the author contextualises the presence of Buddhism in the region, and highlights the importance of Buddhist rock art in Karachi and Kohistan areas.

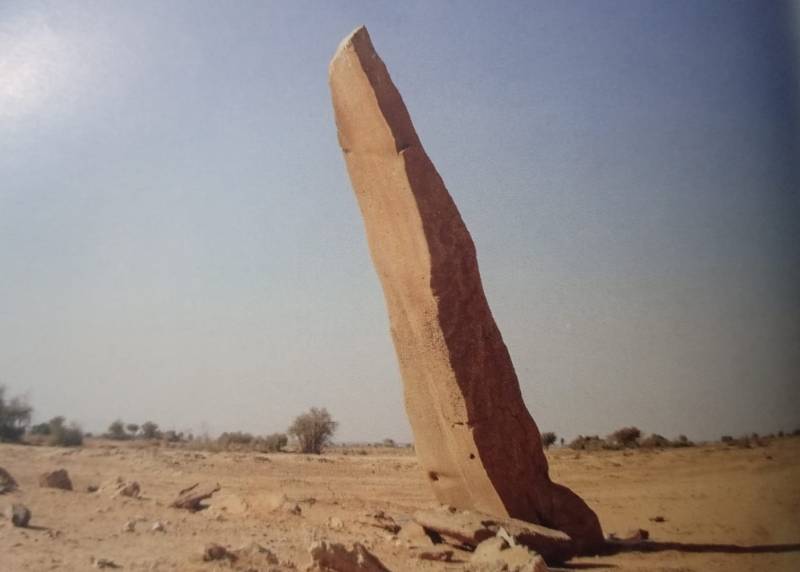

“Megaliths of Karachi” is the fifth chapter of the book. It emphasises the importance of the megaliths of Sindh as crucial elements of Pakistan’s archaeological landscape. The author’s fieldwork is spread widely – it started from 2001, and he worked across the Khirthar, Bado, and Lakhi mountain ranges, particularly in Gadap taluka. He uncovered a wealth of prehistoric and historic monuments. These include stone circles, menhirs, dolmens and stone-carved graves, showcasing the region's rich cultural heritage. However, megalithic sites in other parts of Pakistan remain under-researched. Sindh is home to many, particularly in areas like Thano Bula Khan, Gadap and Malir. In Thohar Kanaro, located 45 km north of Karachi, the chapter highlights notable structures such as the largest stone circle in Sindh and menhirs engraved with cupules, which are significant cultural artifacts.

The author emphasises the cultural importance of megaliths and advocates for more research and preservation efforts. Sites like Kararo Muqam, Burfat and Wankhand are rich in cultural history, with many structures regarded as sacred. However, threats like vandalism and illegal excavations underscore the urgent need to protect these ancient treasures for future generations.

The author calls attention to the cultural reverence that these megaliths still hold for local communities, urging for more research and preservation efforts. Sites like Kararo Muqam, Burfat, and Wankhand reflect a deep cultural history, with many structures considered sacred. The ongoing threats of vandalism and illegal excavations highlight the urgent need to protect these ancient treasures, ensuring that they are preserved for future generations.

Chapter 6, titled with “The dolmens of Karachi,” focuses on the extensive megalithic cemeteries. The author has surveyed megaliths across Sindh since 2001, documenting hundreds of sites, including 16 dolmen sites in Karachi. Unfortunately, many have been lost due to urban development and construction. Notable sites include Garhi Buthi, with over 40 dolmens, and the Tarari cemetery in the Maher Valley, which hosts over 100 dolmens and 5 menhirs. The chapter also explores megalithic art, which includes decorative elements on monuments and menhirs, featuring abstract designs, incisions, and figures.

The author recounts visits to significant megalithic sites in France, such as the Gavrinis passage tomb, known for its intricate carvings. Noting the rich heritage in Brittany, the author emphasises that Sindh has its own important megalithic sites, particularly in the Sindh-Kohistan region. The menhir at Thohar Kanaro displays cup-marks and geometric designs, while sites in Jamshoro and Dadu feature similar markings. He shares that menhirs in Dadu’s Makhi Valley, known as Kafran Ja Chura, are adorned with ancient and modern engravings. Some sites, like the menhir at Mai Shah Rohi, have become venerated objects despite losing their original art. This chapter invites further exploration of Karachi’s megalithic art and its connections to broader cultural traditions.

The title of Chapter 7 is “From Gavrinis to Gadap: Megalithic Art in Sindh.” This chapter discusses megalithic art, which encompasses decorations, abstract images, incisions, sculptures and paintings. Unlike Upper Paleolithic art, which depicts realistic figures, megalithic art is often schematic, featuring zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures, weapons and tools.

This art tradition is linked to a broader Schematic art movement in Late Mesolithic to early Neolithic Europe, especially in southern regions. Common motifs include chevrons, lozenges and cup-and-ring designs, which reflect the ritualistic nature of decorating these monuments to honour ancestors. The author visited several significant megalithic sites in France, such as the Tumulus of Bougon and Gavrinis, where Brittany is particularly renowned for its megalithic monuments. In contrast, Sindh is home to numerous megalithic monuments, particularly in the Sindh-Kohistan area. In the area, menhirs often exhibit both ancient and modern engravings, with the best examples found in Gadap taluka at Thohar Kanaro, which showcases cup-marks and floral designs. However, illegal excavations in the Mol Valley near Nai Drigh have revealed circular pit graves, while in Pir Aari, menhirs are noted for engravings of shoeprints. In the Thatta and Jamshoro districts, some menhirs have lost their original art due to repairs, yet stones like Mai Shah Rohi and those in Jungshahi Baba's cemetery remain objects of veneration, demonstrating the ongoing cultural significance of megalithic art in Sindh as well as Pakistan.

The book concludes (Chapter 8) with a call for thorough documentation of Karachi’s cultural heritage, emphasising the need for a comprehensive understanding of the region's history. Serving as a foundational resource for exploration, it highlights the significance of painted shelters and megalithic sites. Notably, cave paintings in Lahut span from the Mesolithic to the Historic Period, showcasing stick figures, Bronze Age deities, and symbols associated with Nath Jogis. In addition, cupules found in Gadap taluka suggest multifunctional uses, possibly serving as calendars and game boards. Further research is crucial for understanding Karachi's Buddhist heritage, particularly through the study of stupa images, which can be organised into three chronological groups from the 3rd to the 9th centuries. Furthermore, engravings of animal tracks and shoeprints provide insight into the knowledge and practices of ancient hunters, illustrating the deep connection between culture and environment in Karachi's past. In sum, this chapter emphasises the rich tapestry of Karachi's heritage and the importance of continued exploration and documentation.

Let me end this review with the thought that we stand at the crossroads of history and modernity, and this book serves as a clarion call to safeguard our cultural heritage. We must not forget that each site and each story is a thread in the fabric of our shared humanity. It reminds us that understanding our past is not merely an academic exercise but a vital responsibility that shapes our future.

Let us commit to preserving these sites and narratives for generations to come.