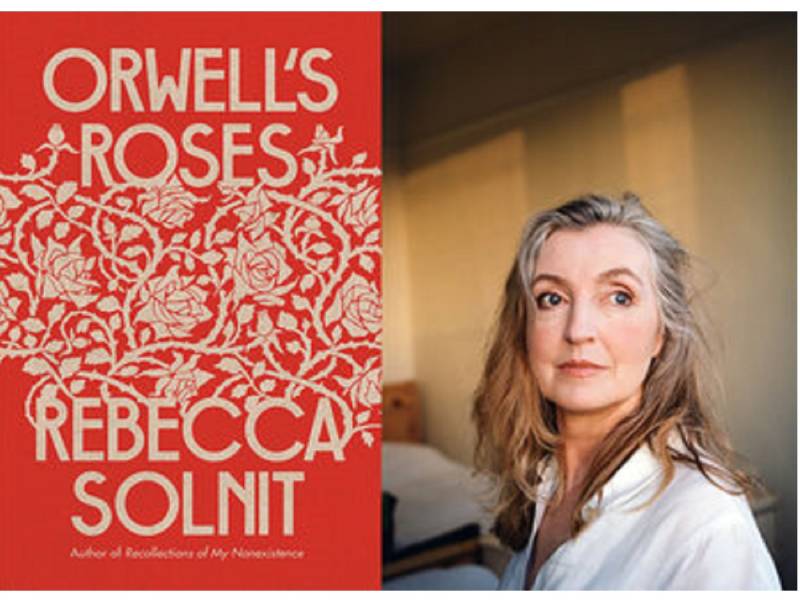

Reading Rebecca Solnit’s book Orwell’s Roses, one discovers a great deal on two topics – the famous writer George Orwell and roses. As Solnit puts it, the book is “about roses as a member of the plant kingdom and as a particular kind of flower around which the edifice of human responses has arisen, from poetry to commercial industry. They’re a widespread wild plant, a many species of plant and a domesticated one, with new varieties created every year, and when it comes to the latter roses are also big business.”

Roses mean everything, which Solnit describes end up meaning nothing. Solnit says that in the Western world they are used as wallpaper and put on everything from lingerie to tombstones. Real roses are used for “courtships, weddings, funerals, birthdays and a lot of other occasions which is to say for joy, sorrow and loss, hope, victory and pleasure.” Solnit writes that they “…crop up not just as ornaments but as aphorisms, poetry and popular song.” Solnit lists the popular songs of the last several decades as: “La Vie en Rose,” “Rambling Rose,” “My Wild Irish Rose,” “(I Never Promised You a) Rose Garden,” “A Rose Is Still A Rose,” and “Days of Wine and Roses.”

Solnit explains that there is a cultural view which thinks that “flowers are dainty, trivial and dispensable” and a scientific one in which flowering plants are thought of as revolutionary from their appearance on earth some two million years ago to their being dominant on land from the Arctic to the Tropics. Solnit goes on to elaborate that there might be evolutionary reasons why we find flowers so appealing, like our domesticated lives we have domesticated flowers, and our life depends on flowering plants.

Orwell’s life was episodic, and a lot of the episodes were influenced by geography. He was born in India where his father was posted and raised in England by his mother in nice towns. He was then sent to preparatory school at age eight where he had to win a scholarship and after that to Eton again on scholarship. After that, since he didn’t have any family money, he had to look for work. He then lived in Burma, Paris and Spain during its civil war, writing during all the time.

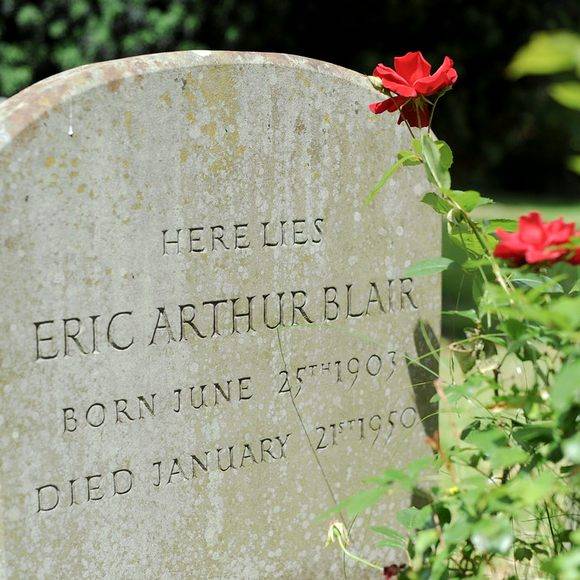

Solnit writes that Orwell became incredibly famous for sentences such as the following in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping the human face – forever.” When Orwell returned from Burma, he decided to become a full-time writer, something his parents were horrified at because of the downward social mobility that writing generally led to, but his aunt helped him out. He began publishing under the name George Orwell to distance himself from the family name – Blair. Solnit explains that perhaps because he was the outsider in his own society, “Each of his novels features an individual estranged from the people around him or her, and those adversaries compound into the system that is society, and society grinds each of its protagonists down.”

When he became a reasonably successful writer, he set home in Wallington with his wife, Orwell planted roses as his hobby. Solnit claims that by doing so Orwell was rooting himself into a particular soil and also in “ideas, traditions and lineages that whether he loathed them or not were his and were all around him.” Or perhaps he was trying to step out of the choices of downward social mobility that he had made by choosing to become a full-time writer. Planting roses was full of ideas of the ‘rural idyll’ and ‘pastoral idyll’ and Orwell was in no way oblivious to all that.

Solnit writes that the year he planted roses he wrote, “In order that England must live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation – a evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream.” And it was a decade later that he returned to his fellow Britons, asking them the pertinent question, “You have got to choose between liberating India and having extra sugar. Which do you prefer?”

Solnit writes that five years after Orwell planted roses in Wallington, he went to write in his wartime essay, “The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and The English Genius,” that the love for flowers was an English trait – a hobby. Solnit continues that he went on to classify flowers as hobbies, and hobbies as the characteristics of people who value liberty and private life. Solnit questions Orwell and asks, “what is it that they love when they love flowers?” which is perhaps a deeper question and one I leave each reader to ask themselves.

What is it that we love when we love flowers in themselves?

Solnit says that flowers are “erotic, romantic, ceremonial and spiritual things…but before a flower is used to do something else, to mark a human occasion, it is in itself an occasion for attention… A flower is a node on a network of botanical systems of interconnection and regeneration. The visible flower is a marker of these complex systems, and some of the beauty attributed to the flower as an autonomous object may really be about the flower as a part of a larger whole.”

Solnit went to a factory in Bogotá to see how roses were grown and assembled in a large factory to send off in aircraft to the United States. She says the workers had a phrase that: “The lovers get the roses but we workers get the thorns.” Solnit goes on to explain that Margaret Atwood claims in a Guardian article that “… Orwell had much more faith in the human spirit than he is given credit for.” The totalitarianism in Nineteen Eighty-Four wasn’t something Orwell thought would arrive, it was something he thought could arrive. Today, so many things are referred to as ‘Orwellian’ – according to Solnit, a quick search of The Washington Post produces 754 results: Orwellian bureaucracy, Orwellian tactics, Orwellian tests for immigrants – the list goes on. To the Orwell who loved roses, today Big Brother is surely here.

Solnit’s writing is poised and elegant and her book a lovely cross between a biography of George Orwell and a history of roses. It is a light read for anyone who is interested in history, detailed facts and how the events of the past have shaped our lives today. I would recommend it to all those interested in love, in flowers and in socialism. By writing this critical book Rebecca Solnit has once again reminded us that she is one of the most prolific writers of our time.